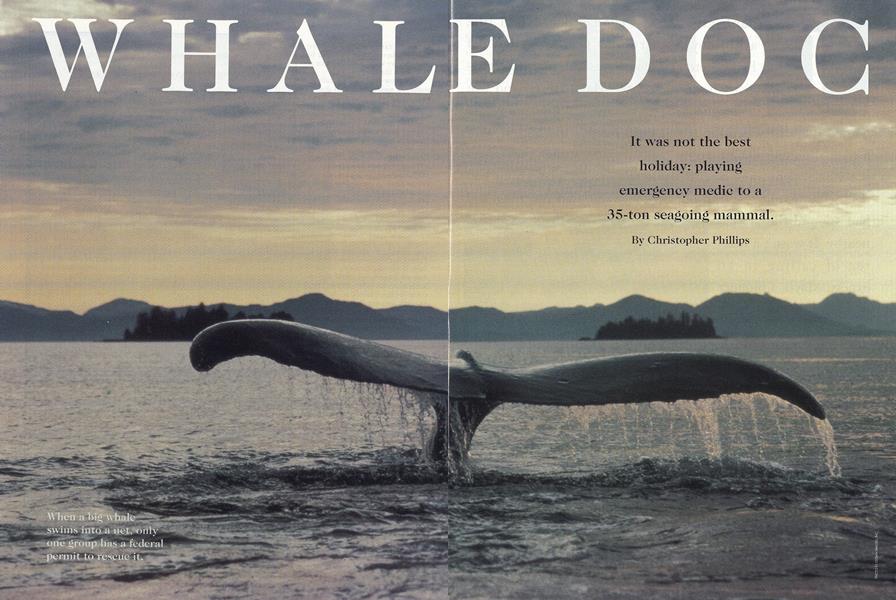

It was not the best holiday: playing emergency medic to a 35-ton seagoing mammal.

Thanksgiving Day 1984 did not feel like a holiday. In a rubber pontoon boat off Provincetown, Massachusetts, marine biologist Charles "Stormy" Mayo III '65 and five colleagues had to rescue a humpback whale named Ibis that was floundering right outside the harbor with a wad of fishing net balled up in its mouth. Either they saved the whale right away or the whale would die. The group had been conducting research out on the water that morning and

had spotted the animal nearby. It wasn't a matter of calling in an expert; Mayo, a pioneer in freeing whales from fishing gear, was the expert. The crew took a long-handled hook and grappled the net that

trailed from the whale's mouth, pulling the boat closer and attaching floats. Ibis went berserk. She thrashed the gray water and rocked the boat before going down in about 200 feet of water. Then nothing, no sound, no movement. Suddenly the floats came flying up, and the whale burst up for air, struggling to get its blowhole above the surface. "It was like a scene right out of Moby-Dick," Mayo recalled years later.

The whale lay still, exhausted. Mayo brought the boat up and began untangling the whale from the gill net, a 200-foot-long weighted curtain of rope. The net had sawn into the flesh during the several months it had tortured the animal, and the emaciated whale"all bones," recalled Mayo was bleeding profusely. It took the team of researchers five hours to free Ibis and watch her swim away.

Mayo has rescued a total of nine big whales; he does not do the work simply out of empathy for intelligent creatures but because the

population has plummeted to the point where every individual counts. "Each time Stormy Mayo saves a whale, he's saving a significant percentage of the population," notes researcher Roger Payne, president of the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. With only 10,000 extant worldwide, the humpback whale is on the U.S. Endangered Species list. More than 13,700 great whales have been killed commercially within the last six years by countries that refuse to honor the international moratorium on commercial whaling. Many whales have been taken under the guise of "scientific research." Others die in gill nets, which is where Mayo has made his public reputation. He is founding director of the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, the only group that has a federal permit to attempt the risky rescues of entangled whales. The group also is recognized as one of the leading research facilities for the study of great-whale behavior, habitats, and migratory movements.

He first learned about whales on fishing trips with his father, Charles Mayo Jr., a 1932 graduate of Dartmouth who was a nationally known tuna sports fisherman. Stormy—who got his nickname from the rainy night on which he was born is a tenth-generation Cape Codder and descendant of a long line of seafarers. After Dartmouth he got his master's and doctorate in marine science from the University of Miami. He and wife Barbara, also a marine biologist, went to work researching microplankton for the National Marine Fisheries Serviceslaboratory in Miami before returning to Stormy's hometown to teach environmental courses out of their home. When they got to Provincetown and began exploring nearby marine habitats, they realized they had the perfect natural resource for studying whales: Stellwagen Bank, a 22-mile-long marine feeding ground in the 40-mile-wide mouth of the Massachusetts Bay between Gloucester and Provincetown. The nutrient-rich waters around this bank of sand and gravel bring great whales closer to the shore than anywhere else in the world.

In 1976 the Mayos founded their center, working out of their kitchen. The group still operates on a shoestring budget, funded by small individual contributions. With a salary of $15,000 a year, Stormy is the highest paid of the staff of 12. He supplements his income by working as a naturalist on whale-watching tours operated by the Dolphin Fleet of Provincetown.

Only a very small part of the group's attempts to save whales involves spectacular rescues (which is fine with Mayo; "they scare the hell out of me," he admits). The center is seeking to find out how many of these whales are dying unseen not in nets, but because their environment is dying. Of the several species of great whales, the right whale is at most risk of extinction. Its numbers have dwindled from about 50,000 in the seventeenth century to fewer than 300 today. The group also is crucial to a two-year, seven-nation attempt to photograph and study every humpback whale in the

North Atlantic. "Whales are in trouble, but more importantly, the oceans are in trouble," Mayo says. "The oceans produce far more oxygen than the rainforests. Whales are worth saving not only because they're life on earth, but because by protecting their habitats we are saving the ocean and the planet as well."

Mayo is doing something besides: an act of atonement. "I have the blood of whalers," he says"My ancestors killed these whales' ancestors. I think I owe them something."

Which may be partly why Mayo speaks with emotion when he recalls Ibis, named for her bird-shaped markings. He didn't see the whale for two years after the Thanksgiving rescue—didn't know whether the animal would survive its ordeal. And then, on a calm day when he was out at sea, he saw Ibis. She had migrated back north, and a calf was swimming beside her. "It made me feel proud."

When a big whale swims into a net, only one group has a federal permit to trscue it.

Stormy Mayo '65 is the whale version of 911.

Father and son at work.

The team studies a beached right whale.

Christopher Phillips is a writer in Takoma Park,Maryland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

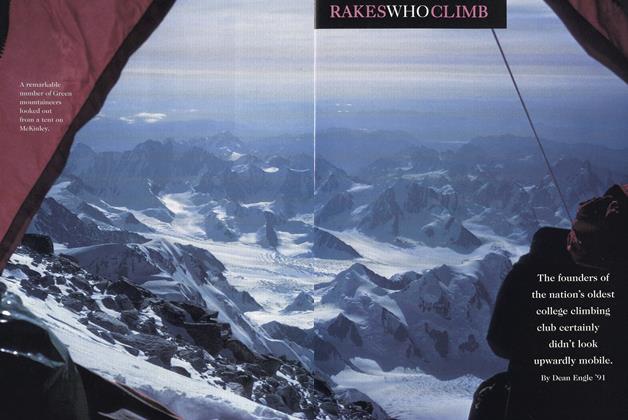

FeatureRAKES WHO CLIMB

February 1994 By Deab Engle '91 -

Feature

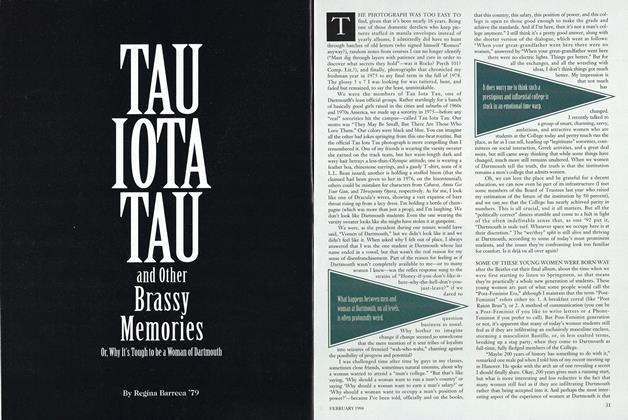

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

February 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

February 1994 By Donald Hall -

Feature

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleA Year and a Tree, Both Rededicated

February 1994

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureOn the Court or Off A Winner

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad Hills -

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

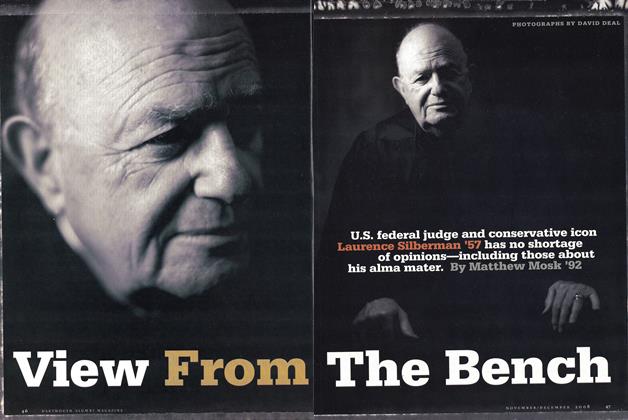

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham