In race relations, the rules of the game are shifting.

The impact of the civil rights movement has had conse-quences that none of us could ever have predicted. Through their own struggle, blacks sparked an awareness of the multifaceted nature of American society, and that movement reinforced other excluded groups seeking inclusion.

We've also seen an evolution of affirmative action. Where once its purpose was negative—to overcome the results of decades of discrimination— now that has been been replaced by the positive goal of representing the diversity of the nation. Colleges now want to enroll and hire not only blacks but Hispanics, Asians, and native Americans as well. Women have joined formerly male or male-dominated institutions, and lesbians and gays are demanding a place.

Black-white polarity, however, remains the most recalcitrant social problem in the country and will continue to haunt a more positive approach to affirmative action—as well as American life in general. Ironically, the group that affirmative action was designed to help seems to have been its least successful beneficiary in recent years, at least on the college scene. The numbers of black undergraduates across the nation have dropped alarming during the past five years. Unless that problem is addressed shortly, the impact on black college faculty and administrators—and on the nation's black community—will be terrible.

At the same time, you have to be pretty myopic not to see that the claims of other groups are inevitable and legitimate. No matter who opens the door, once open, everyone on the outside will wish at least to look in. The problem is to deal with the new challenges without ignoring the old ones.

Like the nation's colleges, America itself has gone through a shift in its ideal makeup. Once it was a city set upon a hill, where the religious and economic adventurers of England set out to fashion a "new order of the ages," as the Great Seal of the United States puts it. Then it became a melting pot that included a mix of people from various nations—European, mostly. Now some say we're evolving further from a melting pot to a salad, where ethnic and other differences are respected and retained. The salad is made up of Latin and Asian components, of women at a different level and manner, and, increasingly, of gays and lesbians. None of this was planned, it just happened.

In a small way, Dartmouth represents the changes in American culture. When I enrolled in this institution 36 years ago, there were only three other blacks in my class. I can recall two Asians and one Hispanic. There may have been others, but not many. Of course there were no women, and the number of gays was unknown—it would have been worth a gay student's undergraduate career to have admitted his sexual orientation publicly.

today, and while what I read in the papers indicates it is still not perfect or even as congenial as it might be, take it from me: there is no comparison with my undergraduate days. There is a level of consciousness, and an honest facing of issues, unknown then.

But the battle isn't over. And for- give me if I sound pessimistic, but the battle will never be over. The resurgence of racism, of sexist and antisemitic and homophobic incidents on college campuses as well as in the general society, demonstrates that the poison of prejudice remains. It can be reduced, significantly reduced. We have proven that. But in times of threat and uncertainty, in times of economic concern or faltering leadership, prejudice will resurface. I am persuaded that xenophobia—the fear of strangers and of the unfamiliar—is endemic to our species. It is the root of scapegoating and group discrimination. And as the numbers shift in American society, xenophobia manifests itself in different ways. Groups who once were so- ciety's outsiders begin to compete with one another. The differences we face are not merely ethnic or visible. The task before us is the creation of an inclusive society at a number of levels. For instance, the homosexual challenge, the most recent and currently the sharpest issue, is to my mind.no less valid an issue than race.

If my own home city of Los Angeles is a harbinger of things to come, the changes this nation faces as a society of distinguishable groups are just be- ginning. Because of the influx of immigrants, there is no majority group there. In Los Angeles County, there are more Asians than blacks. That was unthinkable five years ago. When a majority eventually emerges—as is expected before the next century be- gins—it will be Hispanic, not Anglo.

The rales of the game are changing all the time. If we are to achieve peace and understanding in this dynamic mixture of cultures and races, we will have the taxing job of explaining our- selves to one another for some time to come.

As a black person, I have heard blacks complain about how sick they are of having to explain themselves to whites. That is perfectly understandable. But stop explaining yourself, and you do so at your peril and at the peril of your children. It was John Adams, I believe, who wrote to his political foe Thomas Jefferson after both had left the presidency Adams said they owed it to posterity not to die before each had explained himself to the other.

Prejudice is democratic. The last time I heard a black called lazy in Los Angeles was by a Thai, not an Anglo. The last time I heard a Hispanic ridiculed for riding low it was by a black. If we don't talk and talk and talk to one another, if we don't make people answerable to people different from themselves, we will go back to the days when prejudice, bigotry and discrimination were the norm.

I'm reminded of a particular evening in 1957. I was sitting in 105 Dartmouth Hall for the Great Issues course required of all seniors. Onstage was a professor of histology from the University of South Carolina who undertook in the next hour to demon- strate the inferiority of the black race to the graduating seniors. I had grown weary in those four years of explaining myself, but while the good professor's presentation was distressing to my pride, I was pleased to be able by my presence to give him the lie. What if no blacks had been there?

In every society, in every group, there is an urge toward homogeneity. It is a natural urge, a desire for a condition in which everyone may be at rest. Periods of rest are essential for life. But periods of challenge are necessary for growth. They make us deal with people and issues that stretch and enlighten us at the same time that they make us uncomfortable. God gives us friends, people who share our values and our views, to support us. God gives us neighbors—people we don't choose, and whom we often fear or dislike in order to stretch our values, to test our views, and sometimes to widen our circle of friends by including some of them.

In a diverse world it is well to go to a college that believes in and promotes diversity among its students, faculty and administration. It is a better preparation for the world that's out there than homogeneity can ever give. But there is a price to be paid for talking to one another—for living cheek by jowl—and we ought to acknowledge that price and not kid ourselves. The goal is not just peace, it is also some form of accommodation. While the melting pot is not an adequate image for American society, neither is the salad. We may remain different and at peace only to the degree to which we are the same. We may differ in values and customs to the degree that we agree on other key values and customs. If the Jewish-, or African-, or Hispanic or Chinese-American is distinctly ethnic before the hyphen, the American after must proclaim a shared ethnicity no less real. That means we will always be shifting and jockeying to make the mix work.

The price can be seen at Dartmouth in the issue of the black tables. When I worked here, one of the perennial questions was, "Why do black students sit together in Thayer?" Why come to a white school and then separate themselves? My response was always that they integrated the school by coming, but they find themselves swimming in a sea of whiteness, in class, in dorms, in clubs, in fraternities, and it is useful from time to time to get together and compare notes. To sit down with someone they don't have to explain themselves to. Just to rest for a while in homogeneity. But the answer never seemed to be quite adequate.

Then one day I remembered "Little Big Man,"one of Dustin Hoffman's earlier films. He played a white child captured by the Sioux and raised as one of them. As in most Indian languages, guages, in Sioux the word for one of their own kind means "human being." At one point, Hoffman is talking to an elder of the tribe about the Sioux's being driven farther and farther west by the whites. In the course of the conversation, the old man says, "The Great Spirit seems to have made an endless number of white people, but only a limited number of human beings."

And it became clear to me: the group to which we belong are the human beings. The other groups are some- thing else.

During my tenure at Dartmouth, when whites went into Thayer they did not see the white tables where people like themselves were seated, they saw the black tables. The people at the white tables didn't see them- selves as racially segregated—they were just human beings. Now, as Asian tables or Latin tables are created, the black tables will look less strange. Or, as there are Asians or Latins or blacks scattered throughout the dining hall, we will all look less strange for being all similarly strange. Everybody will have a chance to be seen for who they are, a certain type of human being instead of some departure from the norm.

One of the uses of diversity is to make the strange seem less strange— or, if your prefer, to make the normal less normal. Human beings don't just come in the color or type we ourselves are, they come in all sorts of types and colors. And the sooner we learn that, the sooner we all will be able to deal justly and intelligently with the world of difference.

John Kemeny used to say that when- ever you make an effort to increase the College's diversity by recruiting another constituency, you have to be prepared to give the kind of support— academic, curricular, or social—re- quired to make the effort succeed. There's something to that. But those constituencies aren't the only ones to benefit. To the extent that we are all prepared as individuals and institutions to give more, to that extent do we all gain more—in knowledge, in under- standing, and in community. And to that degree have we all approached more closely that elusive goal the College calls a liberal education.

A diverse campus is good preparation for the world, says former Dean Traynham, but there's a price to pay.

The Reverend Warner R. Traynham '57 was dean of the Tucker Foundation from 1974 until 1983, when he became rector of St. John's Episcopal Church in Los Angeles.

"Prejudice isdemocratic. The lasttime I heard a blackcalled lazy in LosAngeles was by aThai, not an Anglo."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryFresh Heirs

November 1989 By Heather Killerew '89 -

Feature

FeatureA Foreign Correspondent's Essential Skill: Packing

November 1989 By Christopher S. Wren '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

November 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39 -

Feature

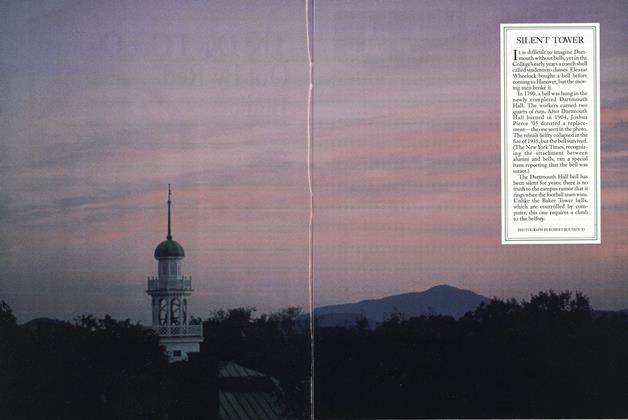

FeatureSILENT TOWER

November 1989 -

Cover Story

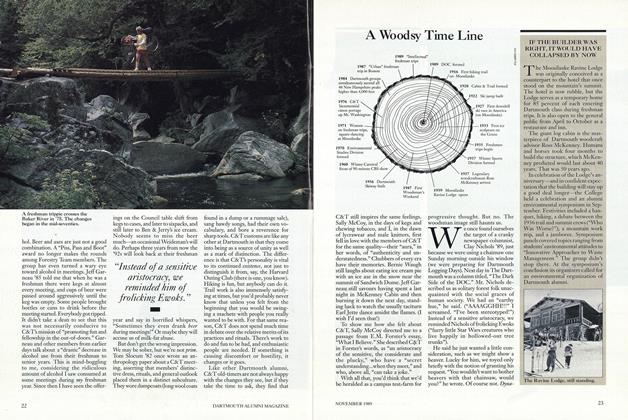

Cover StoryA Woodsy Time Line

November 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFashion Corner: Two Outing Club Looks

November 1989

Warner R. Traynham '57

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Friends' Best Friend

JANUARY 1964 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

OCTOBER 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Features

FeaturesIn the Face of Depression

MAY | JUNE 2025 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July/August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO SAVE THE WORLD IN SIX EASY STEPS

Sept/Oct 2001 By SUSAN HOLMES '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60