When Europeans invaded America, they never really left home.

The accounts that Spanish explorers wrote of their expeditions to the New World have enjoyed a rather ambiguous status: as literary works they appear too factual, and, as historical documents, they seem too unreliable. But in dealing with the politics of imagination—the relation of thoughts and beliefs to socioeconomic and historical realities—the accuracy of these documents is totally irrelevant. What matters is the pattern of inaccuracies, the specific ways in which facts were manipulated and realities misrepresented.

Texts from the Age of Discovery from 1492 to 1600—reveal that the New World was conceived in terms of images and fantasies from ancient or medieval literary and scientific sources. In the process of "making" a new world, the writers merged old dreams with new ones. Consistent with 15th-century acceptance of contradictions between theory and experience, the explorers saw little urgency in using new facts gained through their travels to modify existing theories. For example, accounts of expeditions to the "torrid zone" depicted a reality quite different from the cosmographic theories accepted at the time about the nature of that area of the world. Newly acquired evidence would often be accepted for years alongside the theory it contradicted, thus contributing to the 15th-century illusion that reality was ever-multiplying, open to all possibilities and limited by no constraints.

People assimilated new knowedge into a universal schema in which everything, however strange, had its place, meaning, and function. The 15th century "collected facts as it collected exotic objects, assembling them for display like curios in a cabinet," says the historian J.H. Elliot. The concept of the "wonder room" crowded with exotica illuminates Europe's relationship to America. These rooms—filled with specimens representative of the wonderful strangeness of the New World—allude to the in- finite possibilities of the unknown, the magical space of Utopias and dreams. But the wonder room is also a figure of appropriation, reduction, and control that exposes the politics of imagination in the Age of Discovery.

The preoccupations of the conquistadors reveal the inner dynamics of the politics of imagination. For instance, the classical myth of the Amazons had long been part of the collective imagination. But fascination with the myth in the context of discovery reveals—among other things—the anxiety of a society forced to reappraise itself in response to the possibility of facing in unknown lands the subversion of its own order, of its male supremacy. From Marco Polo to Cortes, repeated reference to the Amazons expresses the endurance of the classical tradition in the collective European imagination, the apprehensions of individual travelers, and the social realities of male power and female subjugation in 15th-century Europe.

At the same time, the collective imagination was ready to perceive the New World as the land of promise where all personal dreams and collective Utopias could materialize. Close scrutiny of the conquistadors' accounts reveals that the explorers tried to bear out this expectation—and were adept at using it to market their expeditions.

Columbus is a prime example. As his exploration of the New World progressed, he repeatedly came into contact with concrete realities that challenged his own fantasies about what he would find. Yet, the more he saw of the new continent, the more he seems to have gotten carried away by his imagination. The gap between reality and description widened. Columbus's identification of Venezuela as the Garden of Eden is perhaps the most incredible of all imaginary representations of the New World. Significantly, it took place during his third voyage, after Columbus had actually explored much of the New World. His claim that Venezuela was Terrestrial Paradise appears to be his desperate attempt to use the powers of imagination to validate his enterprise after his earlier voyages had failed to find the gold, spices, and advanced civilizations promised by Marco Polo—and expected by Columbus's financial backers.

Cortes's writings present another aspect of the powers of imagination. He describes the conquest of Mexico in objective legalistic prose, but fractures in his narrative—the silence of the vanquished, the omission of crucial facts, the reordering of eventsreveal a fictionalized Utopian presentation of the social order that he created and governed. Cortes's imaginary reconstruction of the conquest is invested with the same scientific authority that shapes Machiavelli's discourse. It expresses not just the Utopian vision of a dreamer, but the game of power of an exceptionally skillful political mind.

The dreams of the discoverers were indeed full of fantastic perceptions and Utopian goals that reflected the collective imagination of the time. They also contained the political strategies that laid claim to that unknown marvel, the New World.

For farther reading, I recommend the books below.

Beatrix Pastor, like the Orozco Murals behind her, decodes the discovery of the Americas.

Almost 500 years after Columbus? set foot in America, Spanish: Professor Beatriz Pastor is taking up where the explorer left off. In the mote reaches of libraries in Spain and America she is uncovering worldview that Columbus bestowed, upon the lands he discovered. Read ing between the lines of the reports, and other texts that Colum bus and subsequent explorers sent to European officials and patrons, tor uses literary criticism as a magni lying glass to expose the and expectations that colored observations of the Americas. It was in America that Pastor be gan her journey into the minds of the conquistadors, but she traces the roots of this interest to her departure from her native Spain. Newly married, she had left Barcelona, where she had been studying Latin American literature, to accompany her husband to the University of Minnesota. "The displacement from one continent to caused problems," she recalls. "Everything—from food and clothing to body5 language, facial expressions, and mariners of speech—was different. I found myself reevaluating my life." As she struggled with cultural adjustments, Pastor studied for a in comparative literature and came into contact with the work of Latin American author Alejo Carpentier. When she read his short story "El Camino de Santiago," her life took a turn. "This is the best story on the whole ) process of transformation," she says. "It crystallized my personal interest in into an intellectual question about how people idealize their own culture and impose their fantasies on new environments." Her academic quest led her to examine the transformations of those earliest of Spaniards who came to America: the conquistadors. She has already published a book on the topic, Discitrso Narrativo de la Canquista de America. An English transla tion is due out in the fell of 1991, just before the Columbus quincentennial. Meanwhile, Pastor is back in Spain for a year to research a book about Utopias. But first she is leading Dartmouth students on the Language Study Abroad program in Granada, where she expects to witness some new trans- formations. "LSA is the soul of Dartmouth's language programs," she "Students really have to reappraise a lot of things." Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryFresh Heirs

November 1989 By Heather Killerew '89 -

Feature

FeatureMaking the Normal Less Normal

November 1989 By Warner R. Traynham '57 -

Feature

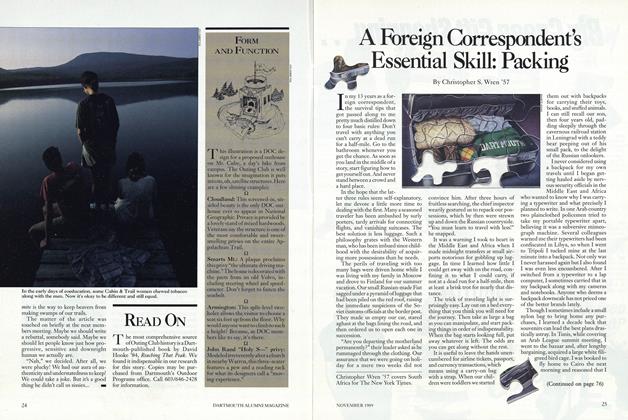

FeatureA Foreign Correspondent's Essential Skill: Packing

November 1989 By Christopher S. Wren '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

November 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39 -

Feature

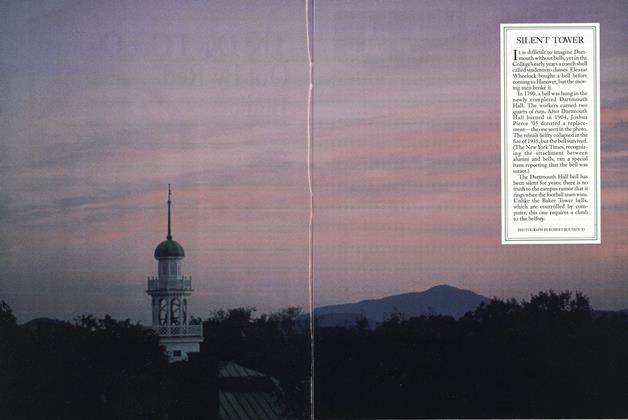

FeatureSILENT TOWER

November 1989 -

Cover Story

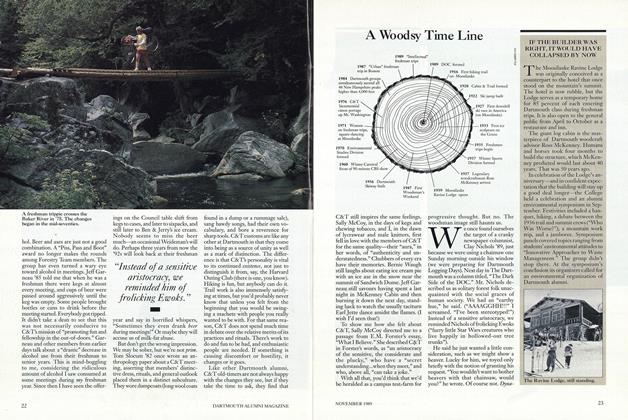

Cover StoryA Woodsy Time Line

November 1989