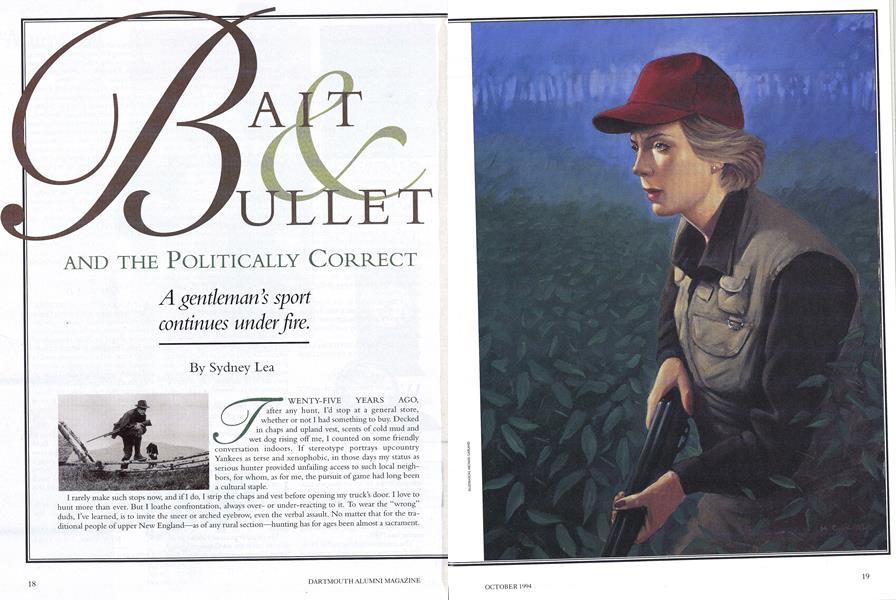

A gentleman's sport continues under fire.

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, after any hunt, I'd stop at a general store, whether or not I had something to buy. Decked in chaps and upland vest, scents of cold mud and wet dog rising off me, I counted on some friendly conversation indoors. If stereotype portrays upcountry Yankees as terse and xenophobic, in those days my status as serious hunter provided unfailing access to such local neighbors, for whom, as for me, the pursuit of game had long been a cultural staple.

I rarely make such stops now, and if I do, I strip the chaps and vest before opening my truck's door. I love to hunt more than ever. But I loathe confrontation, always over- or under-reacting to it. To wear the "wrong" duds, I've learned, is to invite the sneer or arched eyebrow, even the verbal assault. No matter that tor the traditional people of upper New England—as of any rural section—hunting has for ages been almost a sacrament.

The demography is changed utterly, more "sophisticated" folk now on hand to judge such ancient vision as anything but sacramental. They have come to undo barbarism.

According to the testimony of certain undergraduates, this sort of judgment is prominent at Dartmouth too. The members of Bait & Bullet (founded in 1921, and thus the oldest such continuous organization at any U.S. college) feel the apprehensions I've referred to above—the same apprehensions, when I arrived at Robinson Hall, that made me hesitate to ask where the club's first meeting of the year might be held.

Sixteen people attended that meeting. Six were freshmen, five were seniors, six were fishermen only, and one was female (on which generic imbalance more later). There seemed no other categories into which to divide the body, save that there was a plurality of Californians, a fact of which I could make nothing.

The gathering was unofficially chaired by Matt Little '94, though Harley McAlister, another senior, was also obviously perceived as a luminary. Proceedings were impromptu and low-key: Jon Rosenblatt '94, encouraged people to stick with the club, pledging that veteran outdoorsmen like Matt and Harley would be generous with their know-how to neophytes, as others had been to him as- a freshman; older members reminded younger that they could be licensed locally only after presenting a firearms permit, a former license, or certification from a hunter safety program; McAlister advised his colleagues that all firearms at Dartmouth must be registered and stored with campus security; finally, Matt pointed out the availability of B & B equipment, which included "two fly-rods and tons of duck decoys."

Harley McAlister would drag out those decoys on the next Monday, the one just after Columbus Day weekend, which was also the opening weekend for ducks. I arranged to join him and some cohorts then, at a nearby marsh. (By habit, I omit place names.) I offered my canoe, which would get us all onto a well-stationed and brush-covered island.

However excellent the blind, though, when the time came our expedition seemed inauspicious. The duck would of course be spooky after an early-season barrage. The day was predicted to break absolutely clear, too, which would further lengthen odds, no wind or wet to move the prey. As Harley and I set the decoys in false dawn, we heard the last barred owl chant its eight-note aubade into the utter stillness.

We also heard a quack or two in the dark, which would be the final hint we'd get of a duck in the neighborhood —apart from a pair of hooded mergansers, which no real sportsperson shoots. "Little dippers," I've heard them called locally. That morning they bobbed and paddled, cavorting for hours in the near shallows, as I've seen them do over the decades, driving one of my retrievers after another to a near-frenzy. I thought of my poor Topper, dead two autumns before; I could all but see him champ his whitened jaws as the little dippers churned almost within reach—what in hell was I waiting for?

I felt myself smile, though ruefully. For me, a duck hunt seems inevitably reminiscent, even elegiac. Memory takes hold, perhaps because such a lot of that hunt is spent, precisely, in waiting. Were they yet old enough to feel as I did, these Bait & Bullet gunners?

At all events, as the hours passed, there they sat: McAlister, Beth Parento, Sean Hennigan, Rosenblatt, all '94, and Damian Johnson '96. (A chief regret, both for the author and for the membership, is that Matt Little proved unable to join us then, and—because of a term in Spain—in our subsequent conversations.) A flock of Canada geese passed at one point, but so far off it was hard to distinguish their cries from the barking of dogs. The last streamers of pink lost themselves in the sky as the day went increasingly cold—and hopeless.

Yes, to hunt duck in this part of the world is to wait, often for nothing. In its idleness, the group soon turned to the sort of humor any skunked sportsman will recognize: tales of botched shots, collapsing blinds, murderous weather. Not a wing whistled, yet as it turned out we were not waiting for nothing. I at least felt fine to be just where I was, autumn's hysterical trees upended in the pools' reflections, the heavens almost purple, clouds slow and hard-edged; it was fine to witness these young people's camaraderie as their laughter skipped across the slue and rebounded from the high rolling tier to north- ward.

Suddenly Harley crouched. "Is that a pair of ducks?" he whispered, as if we hadn't been speaking at full volume just instants before. Ducks it was: blacks at that, the wariest that fly, especially after they've heard a shotgun or two. They dabbled within plain earshot of our island.

"Well, just to say I tried," Harley muttered, blowing a few hail notes on his call, then cutting back to a feedchuckle.

The blackduck leapt off their pool. I watched them, certain that they'd be out of sight in seconds. But no. Astonishingly, they pumped right at our spread—with the marvelous energy a duck's flight exhibits—low to the water, never even circling, passing over the west side of the island, where one was intercepted. I paddled off to fetch it. As I held that drake aloft, the sunlight caught his vivid blue primaries, which winked and changed shades, an effect that always and oddly reminds me of a cheap raincoat. Feeling the bird's warmth and weight, I also felt a small jet of juice from under my tongue: eating the game is rarely the first thing I think of when I retrieve it, but I'd rather sit down to a meal of wild duck than of anything else I can conjure.

I lay this one down in the Old Town's hull, and almost blinked to behold him there. "Forty years of this stuff," I said, "and I've never seen the like of it."

"Maybe we ought to tell more jokes," Harley answered.

"Better ones too," someone chided.

We all giggled like school- kids.

"It's a good thing none of the wrong people saw," Beth mused. "They'd really believe this was nothing but slaughter."

THE SONS AND daughters of Bait & Bullet believe that such an equation between hunting and slaughter may undergird the hostility toward them of many Dartmouth peers. Like me, they also believe the equation to be ignorant: that incident with the blackduck was every bit as rare as I'd claimed, and the notion of grouse or white- tail or turkey as "defenseless"... well, it is simply absurd, as any hunter could tell you. For which hunter, hearing the rattle of the escaping partridge's wings, the canny buck's snort of alarm deep in the thicket, the sudden, all-enveloping silence that follows the spooked tom's lovesick gobble—which hunter has not cursed and praised, but above all marveled at the defenses of truly wild prey?

As I learned at a follow-up meeting in February, however, it is not merely ignorance that's involved in Bait & Bullet's pariah status, even within the DOC. If Beth Parento voices her frustration over a common and, she insists, not a good-natured greeting—"Hi, Beth! Killed anything lately?"—she is more frustrated by her colleagues' rush to label her. "I not only hunt," she points out, "but I also belong to Bait & Bullet. So right away I'm in some category, whether I think I belong there or not."

By Jon's assessment, attitudes toward Bait & Bullet actually dramatize a larger, collegewide problem: "You're either 'with us' or you're the enemy." The numbers are not even. The past season's expeditions attracted about 20 hunters altogether.

"We are black sheep, even in the DOC." says Harley McAlister. After a pause he adds, "Maybe especially in the DOC." And after another, he admits that Bait & Bullet's own attitudes may be partly accountable: "We don't go to many Outing Club meetings. They don't do or believe things that we can really merge with."

"For me," says Beth, "a prime attraction of Bait & Bullet is just that it's so informal." She argues, to general assent, that hunting is sufficiently personal and meditative that it rejects agenda—including political ones.

It occurs to me that for Bait & Bullet members one great appeal of their club is that it provides relief from politics. But how can this be realistic? As hunters in current society, I remind them, they can't hope to duck political controversy. I feel myself wince, inwardly: again I picture myself in a general store; it's 1994, not 1969, and I warily eye my fellow shoppers as they pick and choose among the imported wines, the whole-grain baked goods, the exquisite specialty condiments.

And yet I want to hold the members to a theme for now. After all, I argue, a club is an institution: why have one in the first place if you don't want to make a statement, if you don't want politics?

The responses are various. Marco Seandel, a senior, and exclusively a fisherman, says that Bait & Bullet provides a way for students—especially freshmen, who have no cars and little knowledge of regional geography—to meet people with common interests. "But again," he cautions, "unlike others we don't try to identify ourselves through organizational affiliation. We get stuck with this 'conservative' label, even though I'd say that in general our politics are actually more on the liberal side; for Bait & Bullet purposes, though, what they mostly are is irrelevant."

"People call us throwbacks," says Sean Hennigan, "which is supposed to mean people who live without any self-inspection."

"Yes," Damian agrees, "and when it's used about a hunter, it means someone who's resisted humanization and 'progress,' the sort of cartoon Neanderthal who goes around clubbing animals...and women."

"How about it, at least as metaphor?" I ask Beth. "The ratio of men to women here right now is five to one. Is that representative of the club?"

"Yes," she concedes. "But it's also representative of American society at large. I don't see why we should make the club look bad just because it reflects that situation, or even slightly improves on it."

I goad her some: "Isn't a college or university supposed to be more enlightened than mass society? Why aren't there more women in the club if it's not Neanderthal?"

How, I wonder, might I answer my own question, virtually all my hunting partners being men? I sense that perhaps I've persisted in my questioning in the hope that Beth may help me. And yet the issue, alas, seems cloudy for her too: "I've never hunted with another woman on campus, it's true," she says. "Some go, but not with us." She frowns in thought for a moment. "Maybe they just don't like it as much as I do."

In any case, she doesn't feel like the odd person out. She recalls that morning on the marsh, the morning of the suicidal duck. "I felt right in place," she says. "I think Harley is great, as a person and an outdoorsman. I've never felt I was looked down on or discriminated against by him or any other member. Not at all."

"We aren't that sort of throwback," says Jon. "Though if you used the word in another way I'm not sure I'd mind it. If you meant someone who valued independence and hated group-think, I'd be proud enough to let you call me a throwback." He edges forward in his seat. "The great thing about these things we do is that means are often a lot more important than ends."

The comment brings us to an intriguing turn, enthusiasm for the discussion patently mounting. The end of hunting may be a kill, but it is only one aspect of the art. Harley compares hunting to his other enthusiasms: "Hiking or rafting, somehow I feel like a spectator. When I'm hunting, I feel like I'm participating, like I'm in the game, in nature."

"There are so many programs now that rich kids can afford," Jon notes. "Like, Eight Great Locations in Alaska! You go to all eight, and suddenly you're a naturalist."

"My cousin in Montana calls it the McDonald's of adversity," Harley chuckles. "I pay you to tell me how to suffer in the outdoors for a while...and then I'm an outdoorsman, simple as that. Very efficient. And there's another argument based on efficiency too. People tell me, 'You don't have to go hunting.' Of course I don't. But instead of just peeling the plastic off some steak I bought in a supermarket, I like to do things from the bottom up now and then."

I KNOW EXACTLY WHAT HARLEY IS talking about, for if I have spent more than four decades in the game woods and the trout streams, I have also spent my entire adult life trotting back and forth between the academy and a writer's desk: Both contexts are extremely mediated ones. Both depend largely on words. And, like any author, I knew—well before trendy literary theory came along to tell me so—that words, however well wrought or assembled, do not represent direct experience.

A word, in short, is no more than a symbol.

The members with whom I speak are 30 years my junior; perhaps because the world they inhabit in their youth is so much more "symbolic" than it was in mine, they have turned to hunting and angling with far greater awareness of their value as primary experiences than I had at a similar age.

And yet I wonder aloud if any of them has ever changed the mind of a committed anti-hunter. "It's like arguing over religion," I suggest. I speculate that this may in fact be another reason for the more strenuous agents of political correctness to regard Bait & Bulleters as throwbacks: anything that smacks of the religious is so easily construed by skeptics as archaic, anti-"progressive."

Beth puts a final twist on all this. For her, a native Vermonter, the sort of hunters' fellowship that draws her to this beleaguered little club is a sign of her fellowship with her northcountry neighbors, however their numbers may dwindle, however different their educational and economic conditions from hers and her college friends'. "And it's nice too," she adds, "to feel that I'm doing something my grandfather did, and his grandfather before him. You could say it does have something like a religious aspect."

THE THOUGHT STICKS WITH ME as I drive home after our final meeting, the roadside trees still bright with last seasons yellow NO HUNTING posters till I get far north of the Hanover-Norwich axis. And I think on my brief acquaintance with these young Dartmouth people, whom, it turns out, I have come to like enormously. Do I like them because they are hunters? Or am I attracted by certain admirable qualities of spirit in them, certain "traditional values" (to use a term that has recently been woefully cheapened) that started them hunting in the first place? For me—the poorest judge imaginable, so much of myself at stake—it is hard to be sure.

At the foot of my dirt road, however, I'm distracted from all such speculation by the sudden apparition of a deer, momentarily caught in the high beams. The animal is very large and—despite this February's record-breaking cold—sleek. Likely some savvy old buck, I imagine, though of course his antlers have long since been thrown down for the wintering rodents to gnaw.

Knowing his enthusiasm for stalking deer, I suddenly imagine Harley McAlister taking up the fellow's wide, heel-heavy track of a cold November morning. The sky is the color of old metal, the first flakes of the year sifting out of it. All about, the woods have that hard, abstract look they take on when no leaves but the odd oak- or beech-cluster cling to the branch.

Then the faces of Jon Rosenblatt, Matt Little, Sean Hennigan, Damian Johnson, Beth Parento, and even the devoted fisherman Marco Seandel: all appear among the gaunt trees. And I myself, against all reason and logic, am transported—as so often I've been in a sporting life—to some odd realm of faith.

FELT MYSELF SMILE, THOUGH RUEFULLY. FOR ME, A DUCK HUNT SEEMS INEVITABLY REMINISCENT, EVEN ELEGIAC.

THEY HAVE TURNED TO HUNTING WITH FAR GREATER AWARENESS OF ITS VALUE AS PRIMARY EXPERIENCE.

WHAT DRAWS BETH TO THIS BELEAGURED LITTLE CLUB IS SIGN OF FELLOWSHIP WITH HER NORTHCOUNTRY NEIGHBORS.

SYDNEY LEA taught at Dartmouth from 1970 to 1979. Hislatest collection of outdoor essays, Hunting the Whole Way Home, is available from the University Press of New England.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

October 1994 By Varujan Boghosian -

Cover Story

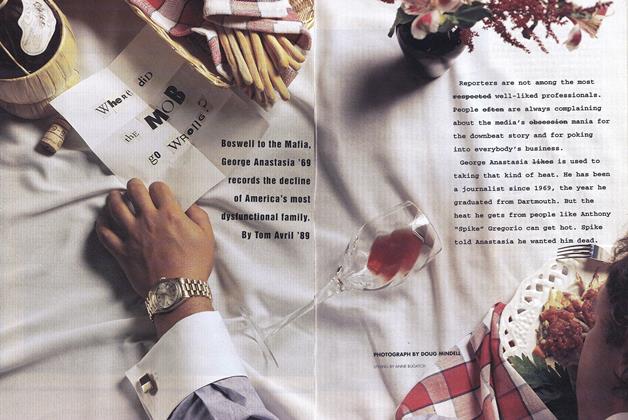

Cover StoryWhere did the Mob go Wrong?

October 1994 By Tom Avril '89 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Testa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Merlino Miss

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA New Look for Reunions

JULY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureCAT NORRIS

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureEB's EDITOR

APRIL 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HOOK VIEWERS WITH AN ADDICTIVE SOAP OPERA STORYLINE

Jan/Feb 2009 By JEAN PASSANANTE '75 -

Cover Story

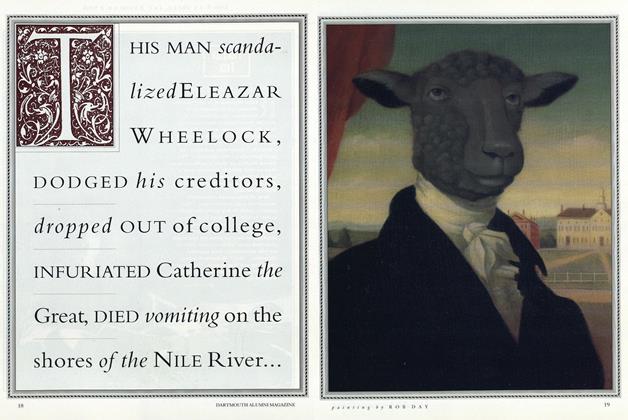

Cover StoryThis Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock

June 1993 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26