• Hugh Brody, Maps and Dreams (Pantheon, 1981). As an anthropologist working in northern British Columbia, Brody pondered the difference between maps that native hunters carry in their heads and maps that mineral prospectors, government officials, or anthropologists carry in their hands. It's a remarkable study of contrasts between ways of looking at the same terrain.

• Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines (Penguin, 1987). Two books in one: Chatwin's journey in search of hidden routes across Australia, and fragments of a never-finished work that argues we are all born nomads.

• Paul Fussell, Abroad (Oxford, 1980). A splendidly opinionated survey of writers in an age before travelers had given way to tourists. • The Vinland Sagas, translated by Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Palsson (Penguin). Travel before maps and travel-books: part fantasy, part bloody realism, the tale of Icelandic rovers who came to North America a millennium ago. Watch out for the one-legged archers.

• Matsuo Basho, The Narrow Roadto the Deep North, translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa (Penguin). Many readers will find this the most difficult book, but patience makes it a friend forever. The record of a seventeenthcentury Japanese priest who went on a pilgrimage to the remotest parts of the central island, The Narrow Road mingles poetry and prose, one taking over when the other falls short.

• Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, TheSelected Letters, edited by Robert Halsband (Penguin). Lady Mary had the Enlightenment mind at its best: tolerant, curious, and witty. She wrote brilliant letters from Constantinople, immune to the priggishness or zealotry that a stay in the capital of Europe's hereditary enemy inspired in lesser travelers.

• Olaudah Equiano, Equiano's Travels (Heinemann). In the mid-eighteenth century, Equiano was a child among the Ibo in Nigeria, a slave in the Caribbean, a Philadelphia trader, a gentleman's gentleman in London, a gunner in the Mediterranean, a voyager in the high Arctic, a settler on the Mosquito (or Miskito) Coast, and a missionary and abolitionist wherever he went. On the surface a remarkably temperate account of what he did and what was done to him, his narrative still quivers with the ambiguous loyalties and feelings of a man who knew his readers from outside as well as in.

• Flora Tristan, Peregrinations of aPariah (Beacon). Anyone who wanted to know what Peru looked like in the 1830s would throw this book aside with an oath. But for passionate involvement in politics and society, Tristan can't be beaten. Her exploits in search of an inheritance do nothing to quell her contempt for orthodox behavior or her scorn for understatement.

• John Wesley Powell, The Exploration of the Colorado River (Dover). Sumptuously illustrated and sumptuously told, this expanded version of Powell's 1870s journals gives us exploration as adventure but also as the systematic expansion of knowledge. There's a confidence and a gusto in his descriptions of Native American life and the southwestern landscape that, with good reason perhaps, can't be found in Major Powell's twentieth-century heirs.

• Norman Lewis, Naples '44 (Pantheon). Lewis served as an intelligence officer in that great but exasperating city during one of the worst moments in its history. He writes with humane astonishment about the duplicity, re- sourcefulness, and courage that he witnessed.

• Zbigniew Herbert, Barbarian in theGarden (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich). Here is a rich collection of essays from 1962 about Italy and France by a most unbarbarous Polish poet hungry for painting, open politics, and good food.

• Sarah Hodgson, Masquerade (Academy). Just before the 1978 revolution Sarah Hodgson went to Iran disguised as a boy, going as far as Qom, the holy city. It's characteristic of Hodgson that the deception worried her far more than the danger. Her speculations about male and female behavior, fundamentalist religion, and the ethics of disguise make this small volume one of the most thoughtful travel books I know.

• Vikram Seth, From Heaven Lake (Vintage). The youngest traveler in the group is also the most cosmopolitan. Now a graduate student in California (the setting of his dashing verse novel The Golden Gate), Seth recalls a hitchhiking journey from Nanjing to Delhi via Tibet. The serious and the comic scenes are equally good. m

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

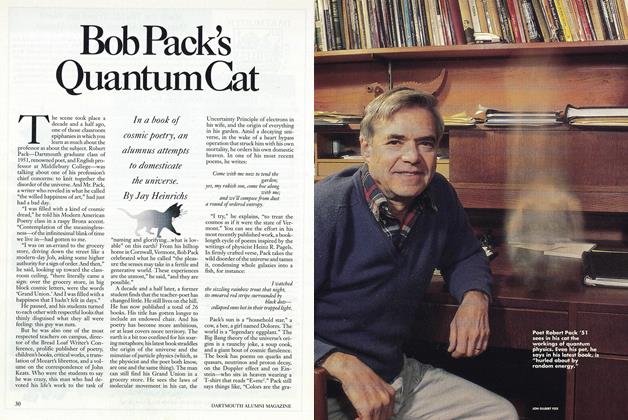

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

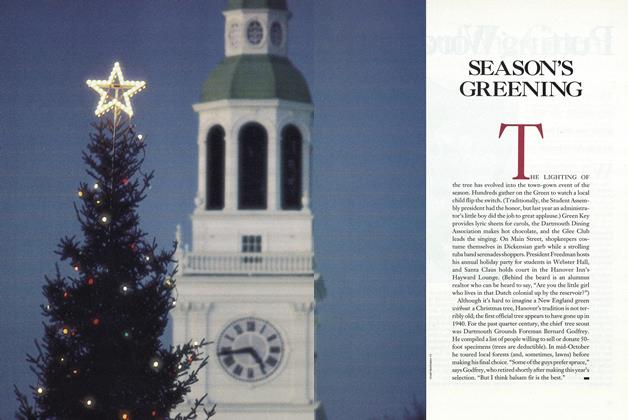

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1989 -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin