When interpreting for the powerful, you talk fast or you don't eat.

"If you see an arm or a foot in a picture, it's probably me."

When Deborah Garretson speaks, Mikhail Gorbachev listens.

As a freelance interpreter, the Dartmouth Russian professor is in a line of work that has brought her close to some of the most powerful players in U.S.-Soviet relations. In the course of duty she has attended a rodeo with both countries' top military brass, toured the Soviet Union with then Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Admiral William Crowe, and worked late into the night with diplomats hammering out the details of the INF Treaty on the eve of the 1987 Washington summit.

More importantly, Professor Garretson got the chance to meet the übiquitous Gorbachev, whom she describes as "an incredibly dynamic man. You can just feel the energy." She also came to know Ronald Reagan, "a likable guy," she says.

Getting close to powerful people wasn't on her mind when she became a linguist, however. The product of an international childhood, Garretson spent most of her youth in Ethiopia, where her father was an advisor to the Emperor Haile Selassie during the Eisenhower administration. Amharic, the local language, came easily, although she concedes, "We spoke very ungrammatical Amharic because we learned it from the kids on the street."

Russian was an interest that developed later in life. She majored in French and minored in Russian at McGill—mostly for the novelty of it. "Russian was just an unusual thing to do," she admits. After graduate work in Russian and Slavic linguistics at New York University, she joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1976. Garretson sees her ability to master the language without growing up in the Soviet Union as motivation for her students. "It lets them know that they can learn Russian to the point where they can do this kind of work," she says.

Her job as an interpreter was actually a contingency plan. "We were the first really big group of women com- ing up for tenure at Dartmouth," she explains of herself and some female colleagues, "and we didn't know what to expect because so few women had been tenured in the past." She took the State Department test, but soon learned that the life of an interpreter is subject to the vicissitudes of the Cold War. "After the Afghanistan invasion, not much was happening in U.S.- U.S.S.R. relations," she recalls. But 1985 was a turning point. That fall she joined the U.S. side in the Nu- clear and Space Talks in Geneva. The Geneva summit followed shortly after and gave Garretson her first chance to work with the top echelons of the American team. She was scheduled to be the backup interpreter for Nancy Reagan and Raisa Gorbachev but was instead called into service for Secretary of State George Shultz. "I was terrified," she says. Yet Shultz turned out to be "very relaxed and easy to relate to." Since then she has worked the Washington Summit, the Joint Chiefs of Staff tours of the United States in 1988 and of the Soviet Union in 1989, and the Nuclear and Space Talks every fall since 1985. Her greatest triumph was the 1987 summit, when Garretson interpreted for Gorbachev at a State Department luncheon. She is not at liberty to discuss specific conversations, but she does profess to have great respect for the Soviet leader. "Folks who actually meet him come away with a very different impression of him and what he's trying to do in the Soviet Union," she maintains. "He's a leader of real stature."

Interpreters are expected to be omnipresent and invisible at the same time. "It's like housework," she says. "If it's done well, nobody notices." They sit behind and between guests at a meal ("Unless you're a fast interpreter, you don't get to eat."), linger several steps behind dignitaries as they walk, crowd into the jump seats in a limousine, and stay out of the photos. ("If you see an arm or a foot in a picture, it's probably me," Garretson tells her students.) Each diplomat brings an intepreter to the table who offers to the other side a precise translation, in tone and content, of what has been said. "Sometimes you'd like to say things differently, but you can't take that liberty," says Garretson. Most of the time interpreters go unnoticed, but the media love to dwell on the inevitable errors. For instance, Newsweek gleefully reported that when President Jimmy Carter visited Poland in 1977, his speech about Polish people's "desires" for the future was translated to the Polish people as "lusts."

Russian is particularly difficult to translate simultaneously because the most important word often comes at the end of the sentence. The real challenge, however, is humor. "Jokes are very hard to interpret," says Garretson. "It is a point of professional pride if you can find some way or another to make them fanny in Russian."

Interpreting has given Garretson a taste of a lifestyle rarely afforded an academic. During this past year she accompanied Admiral Crowe and his entourage on a ten-day, eight-city tour of the Soviet Union. "I'd been in the U.S.S.R. all spring with the Dartmouth students in this decrepit dorm," she recalls. "I felt like I'd gone from the slums to the Kremlin." After all, what is acceptable treatment for visiting dignitaries is protocol for their interpreters. Deborah Garretson may have been walking two steps behind Admiral Crowe, but she was still on the red carpet. Official duties have taken her from a helicopter ride around Manhattan to a jaunt in a troika in Moscow. During her most recent trip to the Soviet capital, she remembers, "the motorcade drove down the center lane with sirens blaring and three lead cars to break the traffic. So you're traveling in the wrong lane at a hundred kilometers an hour. I almost had a cardiac arrest."

Social settings are the real perks for interpreters, because the pressure is relatively low and the occasions offer the best insight into the personalities of the powerful. Garretson says Admiral Crowe has a disarming sense of humor and a "tremendous human dimension." As for Shevardnadze, "He's a Georgian—charming, clever, but drives a hard bargain." Diplomats develop jokes among themselves and even find time to talk about the weather. "People are people," she points out.

Nonetheless, the diplomatic regimen can be grueling. Says Garretson, "You live their lives with them because you are their only means of communication. It takes an incredible amount of work and patience." Duringthe final push for the INF Treaty in the fall of 1987, work went on around the clock. "We had beepers," she says. "We were like medics on call. My last shift was ten p.m. to two a.m." When the two sides do manage to come to terms, the rewards are enormous. "Because of my convictions, it's been an honor to work on disarmament," she says. She still has a pen that was used to initial the 1987 INF Treaty at the Washington Summit.

The thaw in relations has affected the Dartmouth Russian Department as well. "The program is expanding like crazy," says Garretson, and the department is scrambling to find staff to accommodate the new interest. The average number of students taking introductory Russian has doubled during this decade. The number of majors in the language has gone from about ten a year during the 1970s to two dozen in this year's senior class. Dartmouth has two foreign-study programs in the Soviet Union, one in Moscow and a second in Leningrad.

Garretson's involvement with the Leningrad program has given her a taste of what it's like to negotiate with the Soviets. The program has traditionally been taught during the summer term, but when Dartmouth wanted it moved to the spring term to coincide with the Russian academic year, it was Garretson who wrangled with the Soviet bureaucrats to enact the change. "Getting that program moved was a bigger accomplishment than interpreting for Gorbachev," she says half seriously.

The professor now spends her fall terms abroad and the remainder of the academic year in Hanover. "Going back and forth—living in two different worlds—keeps everything in perspective, " she observes. In both worlds, she serves as a role model for her students, a woman who has broken into a field that in many countries is still dominated by men. ("The Soviets don't have women interpreters, period.") The money is good, and as for job satisfaction, Garretson is one of a select few who can say after a day at work that they have moved the world one step closer to peace. M

Russian Professor Deborah Garretson grew up speaking Amharic in Ethiopia and majored in French in college. She took up Russian for the novelty of it.

Garretson facilitates some bilingual schmoozing between the Soviets and Admiral Crowe and wife. Social settings are perks for interpreters.

We put Charlie Wheelan to work whenhe came back to Hanover after a worldtour. He also wrote the cover story forthis issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

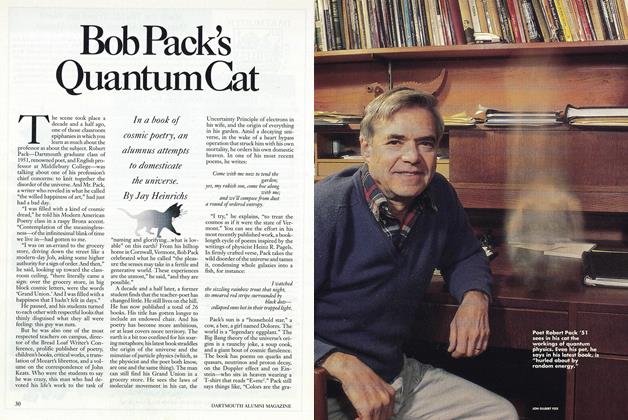

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1989 -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

December 1989 By Fred Louis 111

Charles Wheelan ’88

-

Article

ArticleImprover

MARCH 1988 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAre Americans Saving Enough?

JANUARY 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

OCTOBER 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

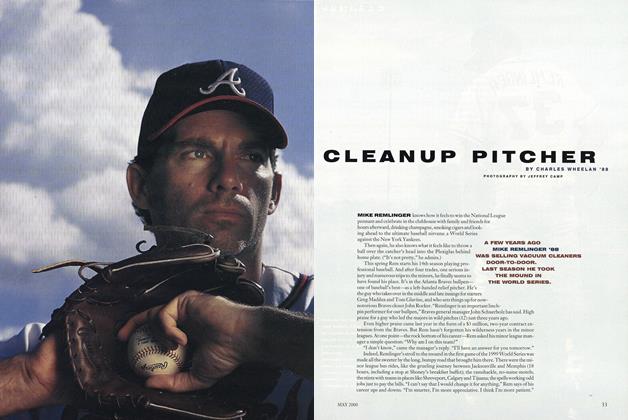

Feature

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

MAY 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Interview

Interview“Look Globally”

Mar/Apr 2006 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleHow to Start a Political Party

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By Charles Wheelan ’88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTucker Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1965 -

Feature

Feature"Doggie" Julian, Master Coach

JULY 1967 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWarming up for 50 years: The yeast of elderly innocence

JUNE 1982 -

FEATURE

FEATURERemnants of a Moment

MAY | JUNE 2016 By GAYNE KALUSTIAN ’17 -

FEATURE

FEATUREHat Couture

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By HEATHER SALERNO -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith