A compassionate circus of literary ringmasters puts the spotlight on contemporary writers

literary magazines: Pamphlet-like productions that sit around in bookstores for months, gathering more dust than glances. Knotty poetry by people with three names. In-groups of writers who publish each other and take years to return your coffeestained, comment-free manuscript. "Thank you for your submission. We regret to say that at the present time it does not meet our needs ..."

These images sum up small-circulation journals for many people. The mental picture they see is something like a plainpaper version of the Ivy League colleges: clubby, intellectually arrogant, outrageously selective, and prestigious out of all proportion. Yale has only about 5,000 students, but kids from around the country are battling to get in. The same thing cabe said for quarterlies like the Hudson Review or the Paris Review: poets, fiction writers, and essayists are braving even higher admission odds in the hope of showing up in 2,000 or so copies.

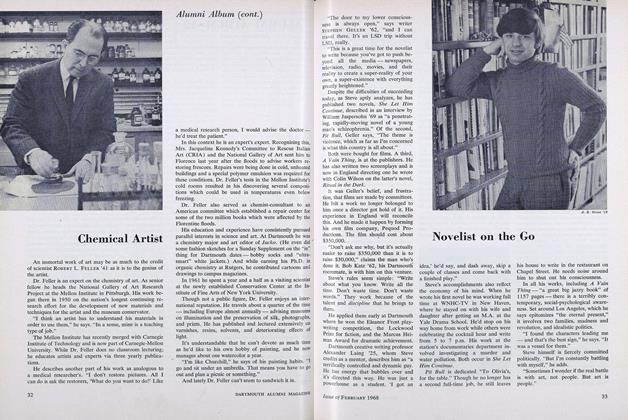

I/anover has an example of each of these choosey, intellectual flagships. Everybody knows Dartmouth, but if you're not an avid reader of serious, contemporary writing, you might not know the New England Review and Bread Loaf Quarterly (NER/BLQ) edited by Jim Schley '79 and former Dartmouth professor (and poet) Sydney Lea. Since its founding in 1977, the magazine's reputation has soared. It is now often metioned in the same breath with venerable and much older reviews. Robert Penn Warren has called it "one of the few literary magazines I feel I must always see."

Remarkably, the editors have won this prestige without growing stuffy. Though necessarily selective (the quarterly gets about 1,000 submissions a month), one office visit will tell you that NER/BLQ is hardly arrogant, and apparently not controlled by people who value reputation or connections over good writing. Schley, who hasn't yet trimmed his hair for the Yuppie decade, remarks: "We have no compunctions about rejecting the big names—Joyce Carol Oates, for instance. She's told us that she likes our comments nevertheless.

"Since there's no money to be made we can say we are really out to publish the best work that we can find. As a rule, we don't solicit. We get stuff from people we want without doing it." Managing editor Maura High adds: "A lot of people appreciate that. They feel we are rooting for those who don't have a huge market value."

One of the unusual things about the magazine is that the editors themselves read every submission and try to make some comment on each one. Anyone who has ever sent off a story or a poem to a journal knows this is a rarity. Lea, Schley, and High are all poets themselves and because of this, they seem sensitive even protective in their role as literary ringmasters. High comments: "We try to cultivate a special relationship with our writers. We try to be compassionate and try to respond to each submission in a helpful way. If we can pinpoint where we feel uncomfortable with the work we'll do so."

While NER/BLQ has been fulfilling its stated purpose of "drawing attention to younger writers" by giving so much attention to submissions, it has published many familiar names as well. Those that have sent in intrinsically pleasing work, that is. In the past year, the magazine has featured commentary, fiction, and poetry by Ann Beattie, Raymond Carver, Richard Hugo, Grazia Deledda (one of six women to win the Nobel Prize for literature), Philip Levine, Seamus Heaney, and others.

"In our role as impressarios," says Schley, "we try to stage each issue as a three-ring circus. Sometimes we've had ten elephant acts in a row and we need a giraffe act. One of the problems is that we don't always have as much from women to publish. In poetry, especially." Adds High: "In general, we don't want to have our 'values' so fixed that people won't send us work because they think it's not our type."

N« England Review began publishing in September 1978. "When the magazine started," says High, "it had to keep reminding people that it was not regional. We'd get submissions from people in the South, and they'd say, 'I hope you New Englanders don't mind Southern writing." In 1982, Dartmouth passed up a chance to adopt the Hanover-based publication. Middlebury College, which runs the prestigious Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, added "Bread Loaf Quarterly" to the magazine's title and with this simple step picked up a respected journal to compliment its commitment to writers. (Editor Sydney Lea is now an adjunct member of Middlebury's English department and a staff associate at the Conference.)

Jim Schley remembers how he joined the staff of the magazine. Writing a simple letter led to a position some people would trade their leather-bound library for. "When I first started, Syd (Lea) was teaching at Dartmouth, Middlebury, and Yale. He couldn't keep up with reading submissions. I knew him, and wrote a note saying 'if you ever need someone to help out . . . His answer was: 'Well, now that you men- tion it, let's try it out.' I lived near Amherst, Mass., and would come up and get a box of manuscripts to read. I was initially very curious to see what others were writing. I made a pact with myself that if I couldn t explain why I was rejecting something, I would send it on to Syd."

The magazine's Dartmouth connections continue even without official ties to the College. NER/BLQ's offices have remained in an historic book-lined study at 13 Dartmouth College Highway. "We like being part of the Dartmouth community, says Schley. "Maura works there (teaching in the English department), I'm an alum, and we've published dozens of Dartmouth professors and alumni. Now, with Dartmouth's new commitments to creative writing, the quality of work we see from the College has gone up. We like it especially when we publish a Dartmouth person.

"Perhaps because of the new academic interest in writing," continues Schley, "because of all the writing programs, we're getting a lot of submissions that are quite good. What's hardest is to separate out the exceptional ones. Writing is more craft-like these days. People are still looking for something that 'takes your head off' but writers are getting more like jazz musicians. They're learning Jelly Roll Morton's stuff before coming out with their own."

Many writers have decided that the NER/BLQ editors favor submissions which, in one way or another, tell a story. There is some truth to this. In a promotional flyer, the editors make the following admission: "Our tastes incline, consistent with flexibility, toward narrative values in verse as well as in fiction, and to a writerly devotion to scrupulous craft." Still, the last thing Lea, Schley, and High would want is to scare off writers or readers with different tastes. "For example," says Schley, "we're starting to publish a lot more lyrical, closely observed poetry. And our special Caribbean issue opened our eyes to some more experimental stuff." (NER/BLQ's other special issue, "Writing in a Nuclear Age," has been published as a book by University Press of New England.) Schley makes a final point: "We do discuss and argue over anything we find interesting. Sometimes we have three-hour meetings. We bring in ethics and all sorts of things."

Schley and High disagree with those who catagorize NER/BLQ as "anti-avant-garde," although they are happy to admit a dislike for writing that is obscure or packed with jargon. Remarks Schley, "We don't go along with the idea that contemporary writers only write for each other. I think that many of our readers are not writers. They are former English majors, people who are interested. We want to stretch the borders for these people.

"NERIBLQ is, in the end, a kind of sampler. It's more reliable than coming across a review and learning that The New YorkTimes says you should buy such and such a book. You read the author here, and then maybe you go out and buy the book." *s?

"We don't goalong with theidea thatcontemporarywriters onlywrite for eachother."Co-editorJim Schley

"We try tocultivate aspecialrelationshipwith ourwriters."ManagingEditor MauraHigh

Co-editor Sydney Lea

The author is a former DAM staff writer and iscurrently an editor at Antioch Publishing Company in Ohio.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Reaffirmation of Mission

November 1986 By Raymond L. Hall -

Feature

FeatureHow "Eleazar" Pulled It Off

November 1986 By FRANK K. KAPPLER '36 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

November 1986 By Bob Monahan '29 -

Article

ArticleTony-winner Jerry Zaks '67: "...in the first place"

November 1986 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleDavid O. Hooke '84: Chubber's Boswell

November 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Sports

SportsDartmouth Soccer

November 1986 By Jim Needham '70

Peter Mandel

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySIGNED ANIMAL HOUSE SCREENPLAY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureFreedom and Discipline

May 1955 By AMOS N. BLANDIN JR. 18 -

Feature

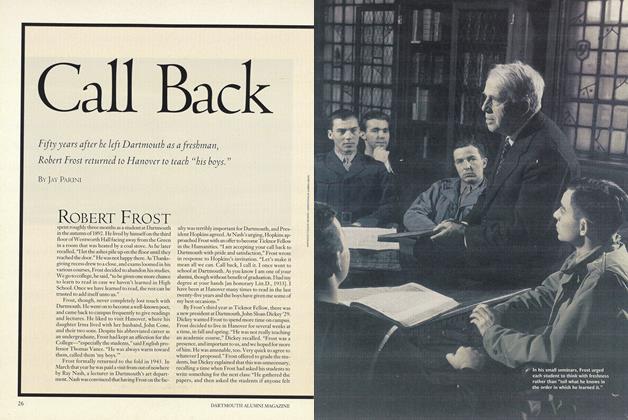

FeatureCall Back

May 1998 By Jay Parini -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

DECEMBER • 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING