The end of a search: alumni in Israel

DARTMOUTH graduates grin and tell humorous stories about meeting fellow alumni around the globe. Burton Bernstein '53, writer for The New Yorker, recently went to Israel for a series of articles on the Sinai Desert. He chuckled, too, when he found that his traveling companion and guide, Clinton Bailey, a lecturer at Tel Aviv University, had entered Dartmouth as he left. Many alumni have visited Israel; authors such as Bernstein and the late A. J. Liebling '24, also of TheNew Yorker, have written about it. But a dozen or so former Dartmouth students all but one born and raised in the United States have made Israel their home.

The list of names uncovered in the College's records of alumni, in literary references, and by letter-writing began to grow. Having lived on a kibbutz in Israel for five months, I was curious to find out more about this group. What had motivated these men to settle in Israel? What directions had their lives taken? Ten from the classes of '55 to '76 answered my questions by mail with frank and honest responses. If these alumni shared experiences at Dartmouth, a common religion, and the decision to live in Israel, not all spent four years in Hanover, not all are deeply religious, and not yet all have become full citizens of Israel. Their experiences and opinions betray a diversity that is not untypical of Israeli society.

Kenny Garon '75 worked on Kibbutz Revadim in the summer before coming to Dartmouth. After the Yom Kippur War in 1973, he responded to the call for workers and took six months off from college. Within a few months, he said, "I ceased to consider myself in the temporary role of volunteer and started instead to give serious consideration to settling in Israel. Thus did I happen to settle in Israel." What does becoming a citizen, which Garon did in August 1975, mean? Responsibilities include army service and reserve duty. "Despite the fact that it takes you away from home and family," he said, "milium service becomes a natural part of everyone's life." Garon is married to Bruria, a sabra or native-born Israeli, and he and his wife quickly did what most young Israeli couples do started a family. He said with pride, "Our daughter not only has the distinction of being a true sabra but she also is a real kibbutznicket."

The image of the kibbutznik may be a familiar one, but actually fewer than five per cent of the Israeli population lives on these communal settlements. "The kibbutz provides for all the needs of its members and is like a separate society within the Israeli society," said Garon. "Consequently, we work without salary and are expected to participate in the running of the kibbutz, in the full spheres of culture and administration, in addition to the work." Not much in Garon's educational background prepared him for work as a dairy farmer, but he contends that "my education prepared me to be open to search, to search for who I am and what is my purpose. The search found the answers that I am a Jew, that I want to live with my people, and that I want to help rebuild the country and redeem the land. These things they do not teach you at aggie school, not even Cornell." Garon said that he did not run away from America: "I only made Aliya [literally 'going up,' meaning migration to Israel], Simply stated, my place is here."

Garon is one of three alumni to have settled on a kibbutz. "Kibbutz is by definition socialism," he explained. People work according to their capacities and receive according to their needs. Mike Madeson '76 was attracted by this ethos. He explained his impulse to emigrate from the United States. "My first problem was my unwillingness to accept some of the gross inequalities between people. If on the one hand some people have lovely homes, ski houses, three cars in the driveway . . . other Americans are feeding their children dog food for lunch." Three years ago, Madeson helped found Kibbutz Yahel, which is located in the desert near the Jordanian border, 35 miles north of Eilat. Today, he serves as treasurer.

ISRAELIS, conscious that the country needs workers, actively solicit youthful volunteers from all over the world. "If young Jews, who do have a choice, would come to live in Israel and constitute a positive element, the chances of the state's survival would be greater," commented Bailey, the Tel Aviv University scholar of Bedouin culture. Many volunteers do go to kibbutzim, staying for a couple of months, or longer if the kibbutz invites them to join. Peter Imber '69 was one of those who joined. "Since leaving Dartmouth," said Imber, "I have been, in chronological order: production assistant for the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite, dairy farmer, soldier, teacher of English as a foreign language, video technician and producer."

Arriving in Israel in 1972, Imber took an ulpan - an intensive course in Hebrew on a kibbutz and married Mira, a woman from the kibbutz. He returned temporarily to the United States to attend a graduate program in motion picture and television production at U.C.L.A. "This country [the United States] is very set in her ways," Imber wrote. "Nothing I could do would change anything here. I could only aim at getting my 'piece of the rock.' Israel needs every man, woman, and child who wants to be there. It's such a small country that an individual does make a difference. In a way, it is enough for me to live my life in Israel, and raise a family that will continue to live there, for my life to have meaning and purpose. Historically, I have made the most important contribution that a Jew can make to Judaism."

Alongside the kibbutzim has flourished another kind of settlement moshavimbuilt on the principle of cooperation rather than communalism. Norman Lavene '55 lived on a moshav in the Jordan Rift near Jericho for six years. When the Six Day War broke out in 1967, he was an investment adviser on Wall Street. "I kept my radio running continuously in my office," he remembered. "When the war ended, I finally decided I was not going to miss out on the most exciting adventure of the 20th century for a Jew." In Israel, he worked first in a bank, but, finding that "uninspiring," he became a moshavnik. He moved to Jerusalem "the city I love" three years ago. "Today, I am a gardener," he reported, "doing physical labor."

The Law of Returns, by which all Jews are eligible for citizenship in Israel, gives the country its melting-pot quality. "I use French and Russian from time to time when talking with immigrants whose Hebrew is weak," said one of the Dartmouth alumni. Although Hebrew, revived and modernized from Biblical texts, is the national language, the streets and marketplaces sometimes echo of English, Spanish, German, Yiddish, Polish, Persian, and Arabic. Immigrants from Europe are called Ashkenazim. Eliezer Gavish '65 is one of the Ashkenazim who emigrated from Poland with his parents in 1950, when he was 13. "After living through the Holocaust, I guess the motivation for going to Israel was clear," he wrote. (Gavish studied in the United States and then returned to Israel to teach sedimentology at Tel Aviv University.) Most of Israel's national leaders are Ashkenazic, but over 55 per cent of the population is Sephardic or Oriental from Africa and Asia. The meeting of East and West is not necessarily harmonious the pot bubbles but doesn't necessarily melt.

THERE is another tension today the role of religion in a country that has always supported a small orthodox population. Aaron Grossbaum '76 went to Israel to explore his religious roots. He studies in Jerusalem at the Yeshivat HaMivtar, "a Jewish parochial school teaching only religious subjects." According to Grossbaum, "The approach taught here appeals mostly to college-educated people so much that it's called the 'lvy League yeshivah.' " It is associated with Michelet Bruria, one of the few schools in the world where the Talmud is taught to women, and it attracts Americans like Grossbaum who have a limited Jewish education. "My family was what I consider a fairly typical non-observant Jewish family in Westchester County," said Grossbaum.

Why the religious urge? At Dartmouth, he had helped revive Hillel. While traveling extensively in Europe and Russia, however, he found that "I was completely on my own for the first time and had to arrange that portion of my life that related to Judaism without the support one gets from the community around him. I became dissatisfied with Reform Judaism and realized that if I wanted to change my religious life, Israel was the place to do it." After graduating from Dartmouth and working in New York, he returned to Israel to study and decided to stay. "I do not feel different and out of place here," Grossbaum said. "The interesting thing is that my feeling of being out of place in America was so subtle that I was not very aware of it."

Jonathan Gershowitz '62, a social worker for Histadrut, the largest federation of labor unions in Israel, had worked in the Jewish community in St. Louis. He took a trip to Israel for two years with his family, hoping to get a feel for the culture. They had every intention of returning to the United States. They didn't. "Being in Israel adds dimensions to my religious life that are non-obtainable anywhere else in the world," Gershowitz explained. "In Israel I can be more fully Jewish. It's important to stress that this is so not because of lack of religious freedom in America but because of the special relationship between the Jew, the Torah, and the land of Israel."

Although orthodox Jews comprise only 20 per cent of the population in Israel, the religious parties hold a trump card in the coalition government and have bargained for special laws no public transportation on Shabbat, kosher restaurants, and national observance of religious holidays. The rabbis have powerfully influenced the civil codes, too there is no civil marriage, and women cannot appear as witnesses in religious courts, for example. Most of the country, however, is not observant. "I find one of the joys of living here is not having to belong to a synagogue," admitted Lavene, the gardener from Jerusalem. "I am totally secular but, of course, speak Hebrew and live according to the Jewish calendar." For many, then, to be Jewish is to be part of a nation with a land, language, and history. To Clinton Bailey, this history "satisfies the desire for roots."

Others told me they came to Israel out of "Zionist motivations." David Fisher '76, for one, said, "I believe that Israel is the homeland of the Jewish people and am directing my life toward the building of the Jewish people and their state." He is doing this as a government urban planner.

Obviously, a Jew is not in a minority in Israel. Frederick Bacon '59, sales director of a medical electronics firm in Rehovot, recalled a conversation from his un- dergraduate days. When he handed in his final exam to Professor T.S.K. ScottCraig, with whom he had studied closely, the philosophy teacher said, "I have watched your handwriting all these years. It is so straight and clear, but somehow so secret underneath. I must tell you it is the symptom of a Jew in a Christian society. You will have to cope with this problem in the future." Bacon laughed, never dreaming that at the age of 35 he would emigrate to Israel. He married a woman he met three days after arriving and they now have two children.

"ONE must be a bit philosophical and have a sense of humor to live well in Israel," Bacon commented in his letter to me. The temperature can hit 110 degrees. Public transportation, although cheap and widespread, shuts down for 26 hours on Shabbat. The economy, based on a six-day week, suffers from severe inflation over 100 per cent in 1979. "Peace as well as war, can be expensive," said one alumnus. Redeploying troops and moving bases cost money, and as security went up, so did prices. "There is, however, one thing different about our inflation," explained Lavene. "Unemployment does not exist."

Taxes, too, are high, probably the highest in the world. "Taxes are necessary, wearying, and amateurishly collected in many segments of the economy," said Gershowitz, the social worker. The money goes in part to fuel the bureaucracy described by various alumni as "incompetent," "superfluous," "horrible," "overgrown," and "obstructive." But, continued Gershowitz, "Its redeeming feature is the Israeli bureaucrat, whose heart melts at almost every appeal to his humanity."

The government, by Grossbaum's standards, is one of the "least responsive democratic governments in the world." He explained that people vote for parties, not candidates, and party discipline remains very strong "the result is that policies change very slowly if at all." He added that "since the vast majority of the people came from Eastern European or Middle Eastern backgrounds, where there is no tradition of democracy, it's amazing that there is a stable democratic government at all." Gavish, from Poland, verified this. "It is still a democracy," he said.

Throughout Israel, soldiers of the Israeli Defense Forces are omnipresent. Women must serve two years, men three. Although their terms may be cut 'back, immigrants are not exempt. "I particularly saw my army service as the key to opening the door to my successful absorption into Israeli society and my acceptance by the Israelis as one of them," said Garon, who purposely chose a course in the army similar to the one selected by most young men on his kibbutz serving as a noncommissioned officer in a paratroop unit. Most Israelis choose to fulfill their army obligations after high school. One alumnus compared it to the American college experience. "When one finishes both," said the alumnus, "he is expected to know what he wants to do with his life and he is con- considered to behave like an adult, which wasn't the case when he entered either of these institutions." Imber, one of the kibbutzniks, hated the year he spent with an artillery battery in the Sinai a 28-yearold among 18- and 19-year-olds. "Reserve duty has been much more tolerable," he confessed. "I like the guys I serve with and accept the 35 days of duty a year as a chance to take a 'vacation' from the everyday problems of home and work. I feel we all try to make the best of our common inconvenience."

For one to three months every year, all male Israelis must serve in the milium, up to the age of 55. It becomes, they say, a part of their lives. To Bailey, it is a "historic privilege." To Bacon, who described himself as a "toy soldier," it is a "cleaning of the head." To others it is a chance to see old friends or meet new ones. "In my last army stint," said one,"I was quartered with six other men. We grew up on four continents and spoke over a dozen languages between us. We represented every social class, from welfare recipients to quite well-to-do."

Gershowitz recognizes the necessity of service but admitted that "going into the milium invariably upsets my kids, wears out my wife, and puts my already understaffed social service into a state of stress." Wives and mothers do not serve in the Israeli army, but they send their husbands and sons off and then live with the fear of what may happen. Lavene, too, mentioned anxiety in describing one of his shifts. "I spent three weeks patrolling the area around the Dead Sea from terrorist penetrations. It took a month to recover from the tension."

The threat of terrorism causes Israelis to be a news-hungry people, tuning in to radios in buses, stores, and homes. "I have had very little experience with terrorism," said Grossbaum, the yeshivah student studying in Jerusalem, the target of many attacks, "but even a little is too much." He related two brushes: "I boarded the Jerusalem-Haifa train almost a year ago. After the train was delayed for an hour and a half with no explanation, I took a bus. On the bus radio, I heard a news report that a bomb had been found on the railroad tracks, just outside Jerusalem, a half-hour before the train was due to leave. Last April, a bomb went off in the center of Jerusalem, killing one and injuring about ten. I, like hundreds of other people, had walked by the bomb an hour and a half before it went off." Grossbaum explained Israel's "paranoia" about security. One must bear in mind the constant threat of terrorism and military attacks that Israel has lived under since the begin-ning of the state. When violent death looms so close in the daily life of people, it affects their attitudes."

These Dartmouth alumni agree on the necessity for military service, but their reactions to the outlook for peace vary. "I was very pleased to hear the news and was looking forward to a more relaxed atmosphere here, a chance to visit neighboring countries and an end to terrorism," said one, although he, and most, are not as optimistic now. Angered, Bailey called the terms of the peace "very bad," and indeed they are for him for he may have lost the freedom he had to roam the desert and mingle with the Bedouins as "Dr. Bailey."

FEW of my correspondents praised Prime Minister Begin, but one lauded the Egyptian president. "Sadat's visit to Jerusalem was revolutionary," he said. And if the agreements cost money, another added, "that is certainly a price Israel is willing to pay for peace with Egypt." But what, they wonder, comes after Sadat?

As . one-time citizens or as dual citizens of the United States, they assessed this country's participation in the negotiations. "The U.S. role is generally positive," according to Bailey. "It wants peace in accordance with its own interests. If Israel does not get better terms, the responsibility is more with Israeli than U.S. leaders." Bailey described his own government as composed of "mostly selfserving, rather ignorant and provincial opportunists." Lavene, the ex-Wall Street investor, judged the United States more harshly: "The U.S., as far as I am concerned, is only interested in assuring itself a steady oil supply." Even if the American role in peacemaking is at once "respected and suspected," in the words of one alumnus, many recognized the need for support.

In confronting the Palestinian problem, expectations and definitions differ. "The 'Palestinian problem' is easily solvable depending on what you think specifically is the 'problem,' " said Bacon, the salesman. He does not think other nations really want to solve it or that they really care about the Palestinians. "The solution," he said, "is obvious. Change 'Jordan' to 'Palestine' and do the Allon Plan most of the West Bank is the province of Jordan." Today, over half of Jordan is composed of Palestinians.

Young Israelis are searching for new answers. Fisher, the urban planner, has participated in interfaith conferences and personal Jewish-Palestinian dialogues. "Yet the solution must be on a political as well as a personal level," he said, and he believes reconciliation is possible. "We cannot stop the quest for peace," Fisher continued. "In the long run it is our only choice. Although the autonomy talks will be long, drawn out, and not too successful, the negotiations must continue. The momentum must not be halted."

Garon and fellow kibbutzniks at Revadim are active supporters of ShalomAchshov "Peace Now" a movement that arose like the Vietnam protest, in opposition to hardline political policies. "There are many of us who would welcome a chance to negotiate with any Palestinians who are willing to accept the existence of the State of Israel in accordance with United Nations Resolution 242 in return for solving their legitimate problems," Garon said. "Our first reaction to the announcement of the Camp David agreement was one of euphoria. I'll always remember that night as one of the happiest and spontaneous celebrations of the kibbutz and, as you know, on kibbutz we know how to celebrate."

Since that time, Garon and his neighbors have seen the main obstacle to peace as "the extreme elements on both sides" and the United States' role as "bringing the other factions into the peace process." If Garon attacks government policies, he admitted, "It also becomes one's privilege to become Israel's staunchest supporter."

MIKE MADESON of Kibbutz Y ahel confronts the question of his age: "Having grown up during the Vietnam War, I have often asked myself the very basic question, What do I believe in to such an extent that I would be willing to fight and die for it should it be necessary?" He admitted that the contradictions of shortterm moves for example, forming West Bank settlements and long-term goals peace complicated the issue. But his answer to his own question was "The right of the Jewish people to a nation of their own after 2,000 years of worldwide dispersion and continuing persecution is a cause I would die for."

Beth Ann Baron 'BO is an undergraduateeditor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

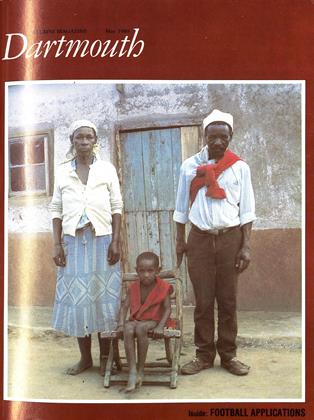

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G -

Article

ArticleVox

May 1980 By Norman R. Carpenter '53

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSidney Chandler Hayward '26

JULY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureEVEN DISAGREEING WITH HIM WAS PLEASANT

May 1955 By ARTHUR H. LORD '10 -

FEATURES

FEATURESA Monk’s Journey

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2007 By Kristine Keheley '86 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

FEATURE

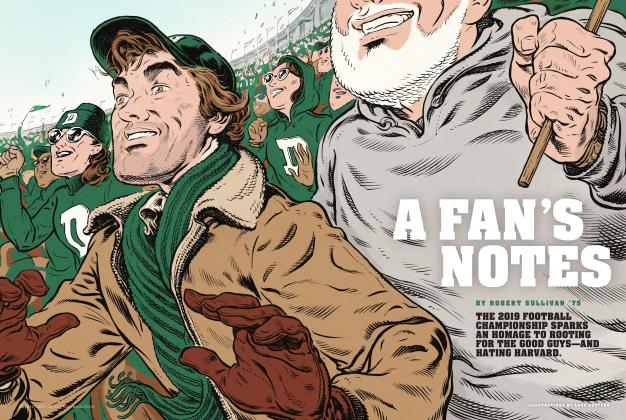

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75