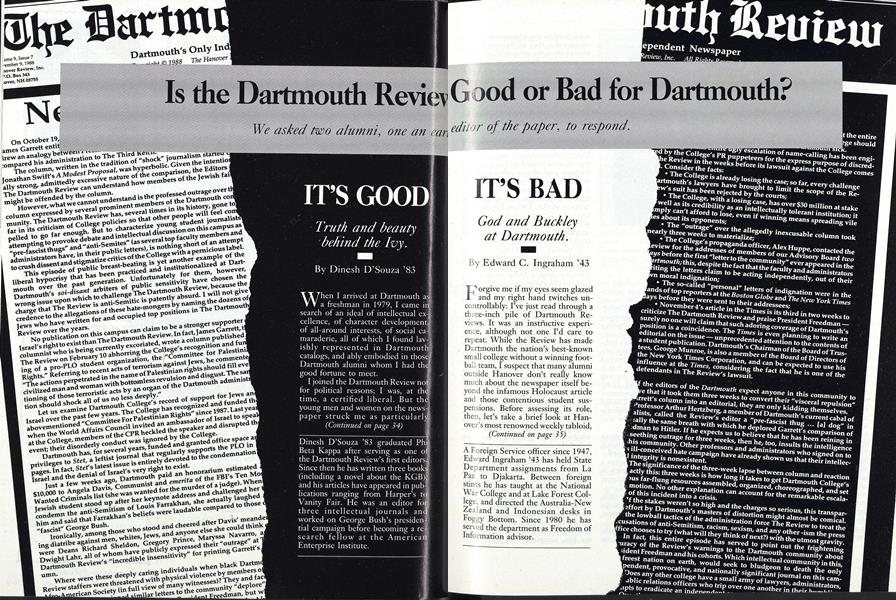

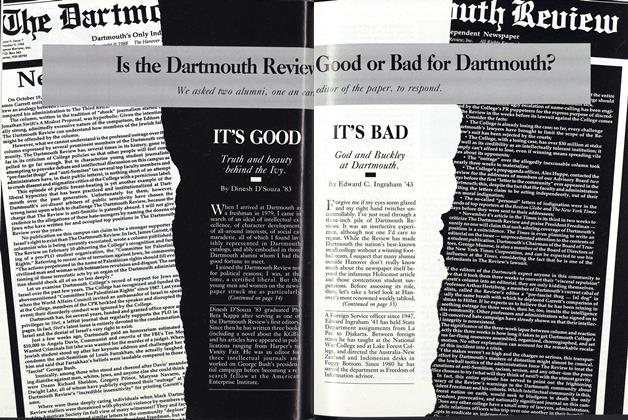

We asked two alumni, one an ear editor of the paper, to respond.

Truth and beauty behind the Ivy.

When I arrived at Dartmouth as a freshman in 1979, I came in search of an ideal of intellectual excellence, of character development, of all-around interests, of social camaraderie, all of which I found lavishly represented in Dartmouth catalogs, and ably embodied in those? Dartmouth alumni whom I had the good fortune to meet. I joined the Dartmouth Review not for political reasons; I was, at the time, a certified liberal. But the young men and women on the news! paper struck me as particularly bright, which is to say passionate about ideas; particularly witty, which is to say courageous in making light of campus orthodoxies; and particularly keen about pursuing the same goal of all-around achievement as I was. I also found Rachel Kenzie, the Review's publisher, particularly beautiful.

Gradually I was swayed to the deep-felt convictions of the founders of the Dartmouth Review, convictions that I dare say are shared by most alumni: the view that Dartmouth is distinctively a college, dedicated to undergraduates and to teaching; that Dartmouth should seek the opinions of alumni with the same zest that it seeks their donations; that diversity is meaningless if it does not extend to tolerance of differing points of view; that students of whatever race, gender or creed deserve to be treated fairly and equitably; that intellectual quests should be supplemented by athletic and extracurricular pursuits; that, above all, there is truth and beauty lurking behind the ivy, for those who are willing to devote their entire lives to the quest.

The vast majority of students on the Review believe in these principles. Today Review alumni count among their numbers a Massachusetts state representative, a nationally syndicated cartoonist, senior policy staff in the Congress and the executive branch, and several widely published writers and commentators. Review graduates have authored eight books in as many years; that is undoubtedly a Dartmouth record. "The Review has produced Dartmouth's most able and accomplished graduates in recent years," Trustee John Steel '54 tells me. "Anybody else would be proud of these students."

I am most proud of the 40 or so undergraduates who devote as much as 40 hours per week to the newspaper, this in addition to managing a full course schedule. The Review is Dartmouth's journalism department, having trained more than 200 students over the past years in the skills of writing, editing, layout, photography, and independent management of a $150,000 annual enterprise.

Nearly every publication at Dartmouth College is either owned or subsidized by the administration. No wonder that they all frequently genuflect before the views of that administration. The Review is Dartmouth's only independent source of news. The paper is at its best with investigative reporting; for instance, what Fortune magazine termed its "stunning" demonstration that more than 100 Indian chiefs, from tribes across the country, favor the Indian symbol and urge its return at Dartmouth.

The Review is the only realistic check on abuses and excesses by Dartmouth professors and administrators, who should be responsive to students and alumni whose tuition and contributions pay their salaries. Largely in response to Review critiques, Dartmouth has revised the mission of the Tucker Foundation, amended Trustee election rules, and opened up debate on the curriculum to include consideration of a "great books" requirement.

Without the Review, alumni would not know that they recently helped pay $4,000 for a hateful outburst by Angela Davis of the U.S. Communist Party. (As an undergraduate, I found that conservative speakers were often denied access to College facilities on dubious pretexts.) The Review registered strong condemnations by several of Dartmouth's art professors of the administration's censorship of the Hovey Grill murals and of religious symbols in Rollins Chapel. Absent the Review, who would hear about de facto segregated dormitory facilities for blacks? Who besides the Review consistently opposes the administration's attempt to roll back the fraternity system, or to bowdlerize the alma mater? I doubt most alumni would know about feminists dressed as witches, throwing red-died tampons before Dartmouth officials, including the former president. How many realize that, for the past several years, special-interest groups at Dartmouth have held a separate graduation ceremony, with separate speakers? (They find the official ceremony to be an endorsement of Dartmouth's white male heterosexual establishment.) The Review made the College Health Service's distribution of safe sex kits, complete with listings for oral-anal sex, "fisting," and "watersports" (urinating on each other), both a Dartmouth and a national issue.

Love Dartmouth though we may, we must admit: these things do happen. It is not disloyal or illegitimate to ask: Is this Dartmouth at its best? Is this what alumni and parents get for their money?

For alumni, receiving the Dartmouth Review (for a mere $25 a year) is indispensable for understanding the issues facing the College today. Partly this is because of the Review's keen reportorial eye (in 1982 the paper won the Society for Professional Journalists' first place award for in-depth reporting), partly because the Review is Dartmouth's intellectual propeller, dominating if not setting the political and philosophical agenda on campus.

"The Review has succeeded where countless tenured professors have failed—in stirring up animated debate on campus on issues such as academic excellence, affirmative action, and freedom of the press." So remarked The New Republic, bastion of American liberalism. Dudley Clendinen of The New York Times called the Dartmouth Review "the best written college newspaper in America." Recently former Dartmouth Trustee Robert Field '43, no friend of the Review, said publicly that he "respects the intelligence and writing ability of students on the Review." Dean Edward Shanahan said he keeps a scrapbook of Review articles. Even President Freedman said he reads the Review often and finds it interesting and thought-provoking.

The assertion that the Dartmouth Review is not "truly" conservative usually comes from doctrinaire leftists for whom the only true conservative seems to be one who salutes and ratifies the liberal status quo. The Review, however, seems authentically conservative to William F. Buckley, Patrick Buchanan, William Bennett, William Simon and John Sununu.

Joining these luminaries are Alan Dershowitz of Harvard Law School, Morton Halperin of the American Civil Liberties Union, and Nat Hentoff of the Village Voice, the three most prominent civil libertarians in the country, who have spoken up for the Review's free-speech right and denounced the barely veiled efforts of the administration to silence the Review.

Despite its national support, the Review is quintessentially Dartmouth. It is a newspaper produced entirely by Dartmouth undergraduates, about Dartmouth, distributed free to students and faculty. More than 5,000 alumni subscribe; the average contribution is around $50. The Review receives no foundation, corporate, or outside funds for its operating budget.

Certainly the Dartmouth Review has made mistakes. Mostly these result from failed attempts at satire or humor. Certainly the Review is too often sophomoric, but I don't get too indignant when I remember that many of its writers are, after all, sophomores. Occasionally the paper shows an excessive relish in controversy; one editor is fond of telling deans that "taking on the Review is like wrestling with a pig. Not only does it get everybody dirty, but the pig likes it."

The Review maintains its jocular edge not only because this gets the paper noticed (more than 90 percent of students read it, according to surveys by the Amos Tuck School of Business) but also because it refuses to take itself or its adversaries too seriously. In every man, as Nietzsche said, there is a child who wants to play. .

opens up its pages to criticism and dissent. Every substantive letter is printed. The Review is quick to admit overstatement and error; several times I have read items entitled, "We Goofed," and they have not been concealed on the back page. The excesses of the Review are incomparably lesser, in number and severity, than those of radical elements among the Dartmouth student body, faculty, and administration. Furthermore, there is no evidence that these Review critics are ever adult enough to admit error. For all its "damn the torpedoes" attitude, the Review always

As a nonwhite sensitive to issues on racism, I find the Review refreshingly free of that condescension toward minorities that is commonplace at Dartmouth and in society. The Review staff has always been both ethnically and philosophically diverse, and charges of bigotry, such as that recently leveled by Trustee Chairman George Munroe '43 in an all-alumni mailing, appear transpar ent, artificial and insincere.

A recent survey showed that almost 90 percent of Dartmouth faculty voted for Dukakis. The Review, as Dartmouth's voice of dissent, provides an alternative voice. Without the paper, Dartmouth would be a duller place, more inert about politics, much more monolithic in its perspective. If the Review is silenced, there will be no one left to be Dartmouth's vox clamantis in deserto, standing up for those truths "ever ancient, ever new" that I came to Hanover to discover, a long time ago as a freshman.

Dinesh D'Souza does a grip-and-grin with a favorite president.

Dinesh D'Souza '83 graduated Phi Beta Kappa after serving as one of the Dartmouth Review's first editors. Since then he has written three books (including a novel about the KGB), and his articles have appeared in pubications ranging from Harper's to Vanity Fair. He was an editor for three intellectual journals and worked on George Bush's presidential campaign before becoming a research fellow at the American' Enterprise Institute.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLoyalty's Roots

April 1989 By Katie Crane -

Feature

FeatureSix Questions for the Candidates

April 1989 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S BAD

April 1989 By Edward C. Ingraham '43 -

Feature

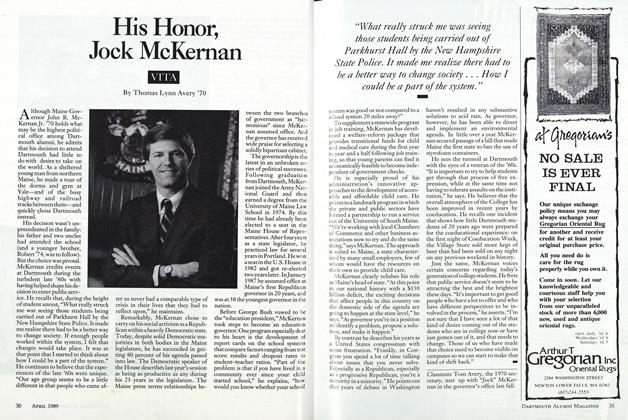

FeatureHis Honor, Jock McKernan

April 1989 By Thomas Lynn Avery '70 -

Feature

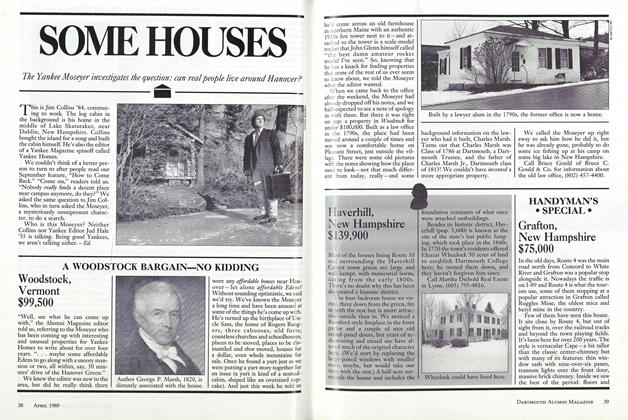

FeatureA WOODSTOCK BARGAIN—NO KIDDING

April 1989 -

Feature

FeaturePlainfield, New Hampshire $295,000 and up

April 1989

Dinesh D'Souza '83

Features

-

Feature

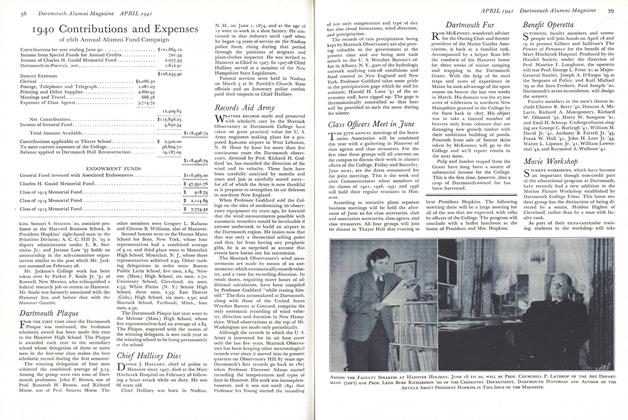

Feature1940 Contributions and Expenses of 26th Annual Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

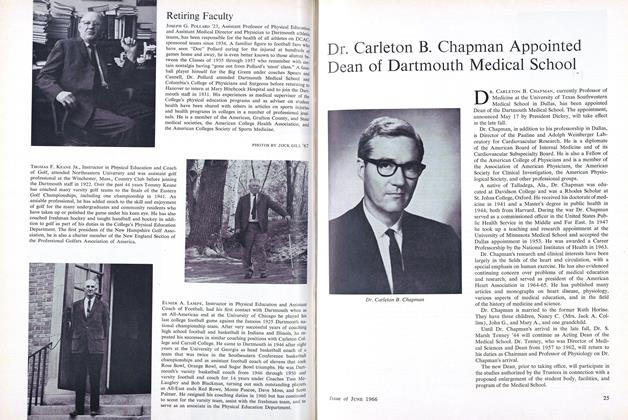

FeatureDr. Carleton B. Chapman Appointed Dean of Dartmouth Medical School

JUNE 1966 -

Cover Story

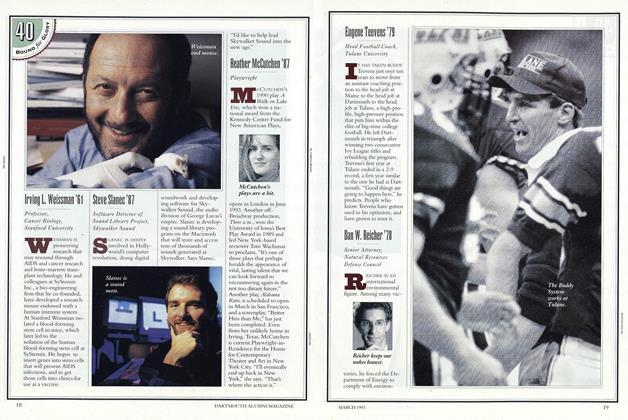

Cover StorySteve Slanec '87

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureDeath and Reunion: the loss of a twin

June 1981 By George L. Engel -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

OCTOBER 1981 By M. B. R -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1951 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER