God and Buckley at Dartmouth.

Forgive me if my eyes seem glazed and my right hand twitches uncontrollably: I've just read through a three-inch pile of Dartmouth Reviews. It was an instructive experience, although not one I'd care to repeat. While the Review has made Dartmouth the nation's best-known small college without a winning football team, I suspect that many alumni outside Hanover don't really know much about the newspaper itself beyond the infamous Holocaust article and those contentious student suspensions. Before assessing its role, then, let's take a brief look at Hanover's most renowned weekly tabloid, distributed free to students of all races, colors and creeds.

The Review wasn't quite what I'd expected. Anticipating a heavyweight blend of the National Review and Mein Kampfi I found myself wandering fitfully through National Lampoon land. Sophomoric, sure, but this was more than that, a sort of paranoid sophomoria. Plowing through its pages, I found a few bits of tolerably sharp prose; much that was embarrassingly poor; humor occasionally successful, more often leaden; and a resounding adolescent pretentiousness. The journal responsible for such havoc on the Hanover Plain turned out to be a pretty dismal product, even for a clutch of 20-year-olds. Asked to grade it, an English professor (other than Professor Hart, of course) might waver between Cminus and D-plus.

Despite the Review's commitment to "the great ideas of Western civilization," I looked in vain for a scrap of cultural content (not even a saving quote from Nietzsche). So what do they write about? Mostly the usual campus controversies: vehemently defending fraternities; deploring retrictions on student behavior at football games; touting the Indian symbol; snarling at other student organizations, especially those representing minorities, women and gays; grousing about Thayer food (shades of my youth!), and, above all, denouncing—endlessly—the College administration, its policies and selected faculty members. When they do address serious College issues, they follow the invariable rule of thumb that anything the administration does is not only wrong but dishonest. Thus the Presidential Scholars program is a fraud, the Council on Student Organizations cheats in distributing funds, the Alumni Fund "fakes" its figures.

Sports are generously covered, with Dartmouth teams defiantly labeled "Indians," a word one ambitious reporter managed to use 11 times in a single short article on women's hockey. The world outside the College is addressed largely by several pages of not very funny oneliners and such choice articles as "Dukakis Makes Doctors Sick" and "Did Teddy Kill Mary Jo?"

Although I'd read President Freedman's statement, I was unprepared for the Review's unrelieved nastiness. A freshman who wrote a critical letter to the editor is berated for "organic stupidity." President Freedman and his staff (along with "deanlette Mary Turco") are "interlopers ... liberal fascists . . . masters of distortion" busily "spreading vile lies" to impose "college tyranny." This sort of drivel flows endlessly through the Review's pages, on and on and on. Personal attacks on individual faculty figures descend at times to the level one would normally find scribbled on a lavatory wall. Rather than journalism, one gets the impression of adolescent resentment run wild.

In one area, though, I'll have to admit that the Review staffers are preeminent. If there's a single halffavorable sentence in a letter or magazine article wholly critical of the Review, they will locate it, rip it bleeding from context, and quote it triumphantly as the author's ringing endorsement of their position.

A decade ago, when the State Department sent me off for a year to bring the wisdom of Foggy Bottom to a dozen colleges in the Middle West, I became familiar with a variety of student publications. Some were excellent, others as scatterbrained as the Review. None, however, remotely approached it for sheer venom. And, significantly, nobody beyond the home campus ever paid the slightest attention to any of them. If the Review were just another of those student-produced journals, different from the myriad that enliven college campuses only in its bloody-mindedness, the College should be able to endure it unenthusiastically but without too much discomfort. One might even argue tepidly that the damned thing be welcomed on the grounds that any form of student intellectual expression, however tasteless, is better than none.

It's not the Review's unsavory content, however, that's produced what most recognize as a serious problem for Dartmouth. As every alumnus who hasn't spent the past year in Antarctica knows, the Review has become a problem for one reason only: a group of highly motivated outsiders have been sponsoring it, guiding it, providing it with mind-boggling publicity, finding White House jobs for its alumni, and using it to promote their agenda. Through their support, the Review has become something very different from the normal campus publication. No, it's not an "independent" voice, it's the product of its sponsors.

The tax-sheltered sponsors portray themselves as white knights defending traditional values against eight years of misguided, liberal-tainted College administrations that have jettisoned dear old Dartmouth in favor of enforced scholasticism, de-emphasized athletics and pandered to noisy minorities. The Review is their tool for fighting the apostasy.

Who are they? The Review's advisory board includes the publisher of the National Review, a former editor of Sun Myung Moon's Washington Times, two right-wing columnists and a clutch of other prominent conservatives— none of whom, interestingly, went to Dartmouth. We also have special guru William F. Buckley, the odd mix of wealthy alumni who make up the Hopkins Institute, and some (although by no means all) of the prominent names that stud the pages of the shrill fund solicitations I keep getting from the Review. In short, a representative group of today's militant right'. Mindful that exposure to paranoids begets paranoia, I'm not suggesting a conspiracy. Let's say they simply pursue the same tactic at the same time.

While much of their agenda for the College seems backward-looking to the point of nostalgia, the white knights have every right to press it on the College. Classmates whose opinions I respect (well, sort of ...) are even willing to give credence to some of their arguments. Let me take a deep breath and assume for the sake of argument that they're right and I'm wrong. I'd still submit—in fact, I'd shout it from the housetop that fostering a group of smart-ass undergraduates to engage in a sort of journalistic terrorism is a deplorable way to advance any cause.

These young gunslingers have distorted the always-delicate campus relationship among students, faculty and administration, turning speech into invective, debates into shouting matches, and drowning out serious discussion. No one will deny that the College administration, being human, occasionally makes mistakeslike that silly sex-kit program a few years back. In the hands of the Review, however, each minor administrative blip becomes a deliberate, shameful assault on our fundamental liberties. This at times can be amusing. But it was not at all amusing last year, when three of the brats went too far, sassed a professor and were suspended. Whatever the merits of the case, I found it deeply offensive that their adult handlers turned the occasion into a public-relations spectacle, invoking columnists from Buckley to Nat Hentoff (who should know better) to proclaim a mythical threat to freedom of the press. The College has been subjected to what seems to me grossly unfair publicity as well as those costly harassing lawsuits.

Not all the Review's victims are the people it attacks. Perhaps the worst thing the handlers have done is to inflate the egos and destroy the perspective of the young students whom they've adopted. Last November multitudes of "60 Minutes" viewers watched the Review's suspended 21- year-old editor, after radiating neoadolescent snottiness, blurt out plaintively to Morley Safer that "All I want to do is pursue stories . . . like you guys do."

Is the Review bad for Dartmouth? Of course it is. Simply stated, we have a subsidized alien presence on campus It has—to borrow the phrase poisoned the campus .atmosphere: harassing students and faculty, insulting minorities, provoking overreactions from its faculty victims, and undermining the whole concept of civility on campus. The annoying thing is that the Review would almost certainly fade away if one could only pry loose the bony fingers and, especially, the bottomless pockets of the outside handlers.

In the real world, of course, that isn't going to happen. The Review will remain the toy of its sponsors. On the other hand, Pollyanna tells me that there are signs the crisis has peaked and may dwindle away as the novelty of pit-bull student reporters wears off, the lawsuits wind down, the columnists find something else to write about, and the alumni Indian symbolists as well as effete liberals begin to realize what the Review is really doing to the College and the loyal sons (O.K., O.K., daughters too) who love her.

As the Arabs say: Insh'Allah!

Ed Ingraham contemplates The Dartmouth Review.

A Foreign Service officer since 1947, Edward Ingraham '43 has held State Department assignments from La Paz to Djakarta. Between foreign stints he has taught at the National War College and at Lake Forest College, and directed the Australia-New Zealand and Indonesian desks in Foggy Bottom. Since 1980 he has served the department as Freedom of Information advisor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

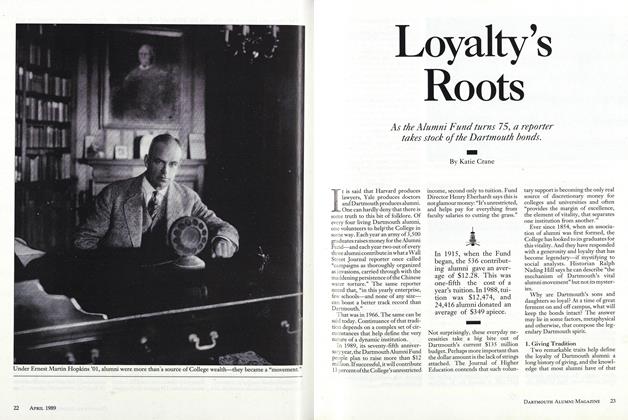

Cover StoryLoyalty's Roots

April 1989 By Katie Crane -

Feature

FeatureSix Questions for the Candidates

April 1989 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S GOOD

April 1989 By Dinesh D'Souza '83 -

Feature

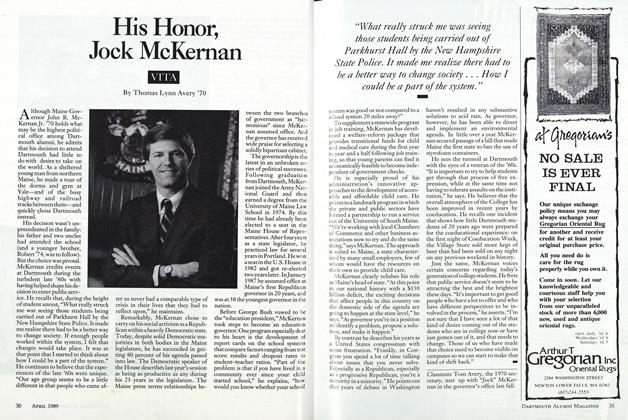

FeatureHis Honor, Jock McKernan

April 1989 By Thomas Lynn Avery '70 -

Feature

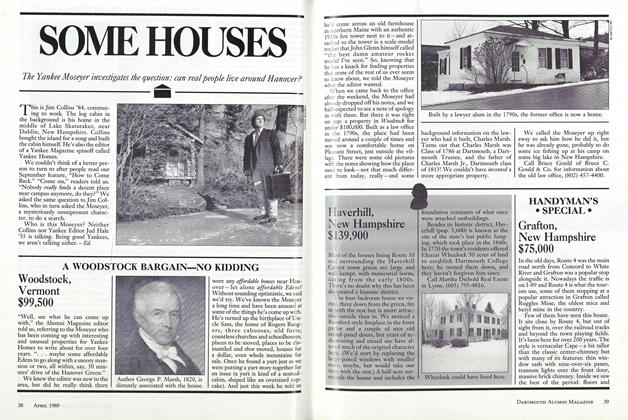

FeatureA WOODSTOCK BARGAIN—NO KIDDING

April 1989 -

Feature

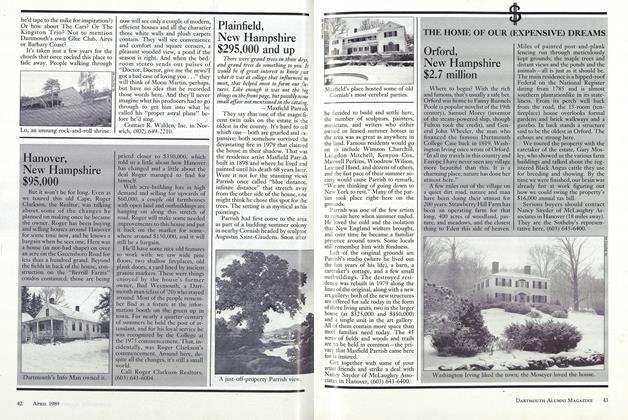

FeaturePlainfield, New Hampshire $295,000 and up

April 1989

Edward C. Ingraham '43

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRevival of the M.D. Degree

APRIL 1970 -

Cover Story

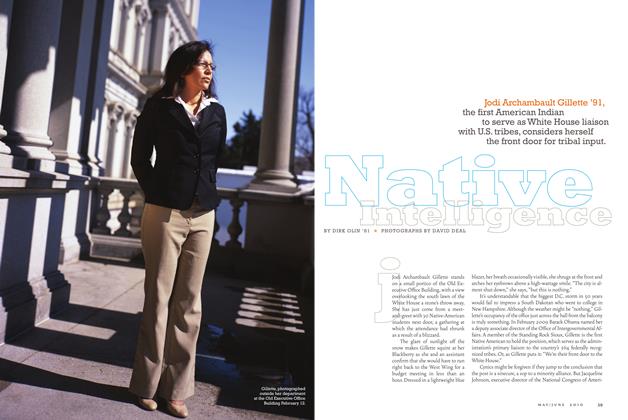

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

Nov/Dec 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

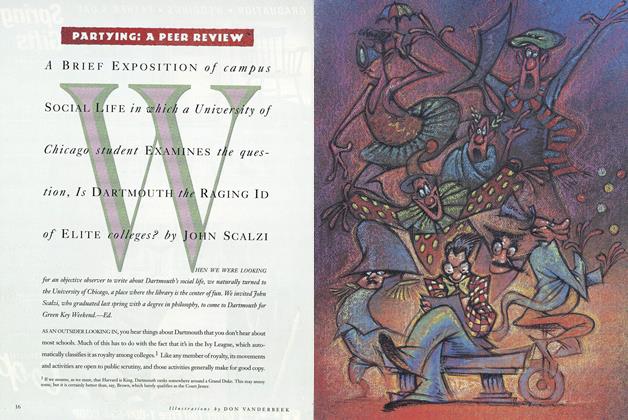

FeaturePARTYING: A PEER REVIEW

MAY 1992 By John Scalzi -

Feature

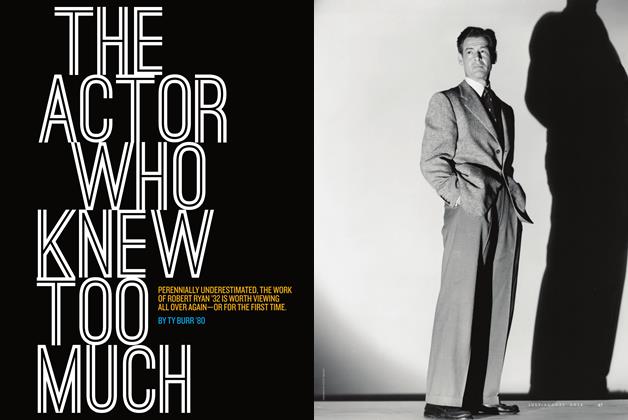

FeatureThe Actor Who Knew Too Much

July/August 2012 By TY BURR ’80