IN APPEARANCE art history professor Artemas Packard was the epitome of the dashing Hollywood British WW I flier; classic profile, trimmed mustache, dark, piercing eyes in the John Barrymore, Ronald Colman model. And perhaps he was trying to reinforce that image when he tried to introduce a special feature to the art history majors' senior seminar.

The English Department had weekly teas for majors, served by an undergraduate in a white jacket. Artemas envied this ancient Oxbridge touch and sought to top it in eruditeness by adding a wine-tasting ceremony to our deliberations. The bottle of Chateau La Tour 1925 was a gift from his own pocket. He brought it with a package of paper cups to the ground-floor seminar room in Carpenter Hall. Eight of us sat around the table, we in our corduroy slacks, our professor in his Harris tweed jacket with leather elbow patches. At a break in our art discussion he introduced us to the colorful history and unique characteristics of the wine. He went on about the importance of region, grape, color, bouquet, and age. Then just as we thought we would never get to taste it, he described in some detail the proper way to decant the elixir. Holding the bottle at just the right angle so the wine would leave the neck smoothly, he poured a few drops into the eight Lily cups. Then he passed his cup under his aristocratic nose, proclaimed the aroma up to snuff, and put it down. We were directed to do likewise. We did so, reverently. I think I sneezed, discreetly. Then he described the pace—slow—of the actual sipping, allowing the liquid to circulate around the teeth, gums, and palate. Then, and only then, were we to close our epiglottises and let the wine slide down our throats. He did so with a sigh and raised his eyebrows to signal that we could now imbibe.

We collectively raised our cups to our lips and, with many a sidelong glance to be sure we were not early or tardy, slowly drank a few drops. But when we put our cups down we noticed they had left a distinct wet ring on the table. Some of us pulled out our hankies and hurriedly wiped off the evidence. Others examined the lower edges of the cups and discerned a few red drops growing there. We reached for the unused cups and put our leaking cups into them as surreptitiously as we could. Without comment Professor Packard did likewise. However, the spell was broken. He went on comparing the vintage we were enjoying to others from other years and vineyards. But our attention was diverted to the likely event that we would soon run out of cups as we continued to put fresh ones under our individual collections. As the stacks of soggy cups continued to dissolve before our eyes, our concern for the varnished walnut conference table increased.

Finally Artemas acknowledged defeat and released us. As we filed out, he was heard to mutter something about selecting a more satisfactory brand, perhaps the Dixie line, and the fact that, though oil and water do not mix, apparently alcohol and wax mix only too well.

If clear-plastic wine goblets had been invented then, Professor Packard might have repeated the experiment. But he did not. And the ritual never became an Old Art History Majors Tradition.

Packard wished it were in Dixie.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryGetting Things Right

March 1995 By Donald Goss '53 -

Cover Story

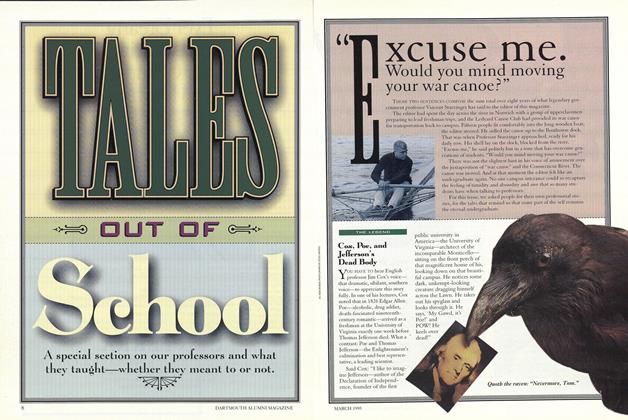

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

March 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDiseased With Poetry

March 1995 By Everett Wood '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryQuite Good

March 1995 By Abner Oakes IV '81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPoesis

March 1995 By David Bradley '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRousseau Cops an Exam

March 1995 By Philippa M. Guthrie '82

John R. Scotford Jr. '38

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

JUNE 1959 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

November 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

FEBRUARY 1991 -

Feature

FeatureTHE HOPKINS CENTER

MAY 1957 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Feature

FeatureThe Green Curve of the Future

JANUARY 1969 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

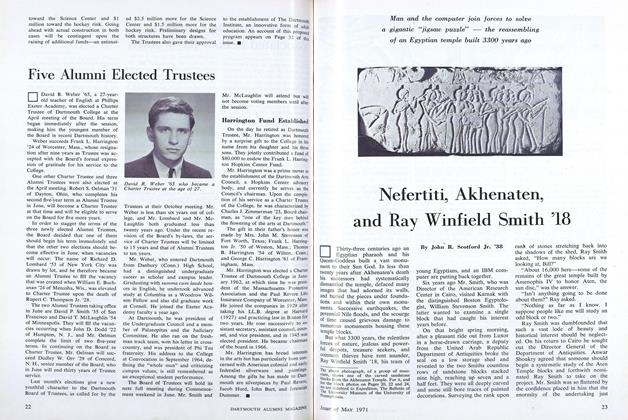

FeatureNefertiti, Akhenaten, and Ray Winfield Smith '18

MAY 1971 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe President on Campus Life

January 1954 -

Feature

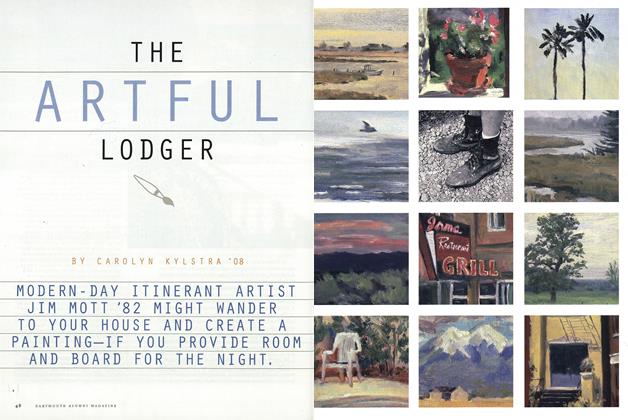

FeatureThe Artful Lodger

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Cover Story

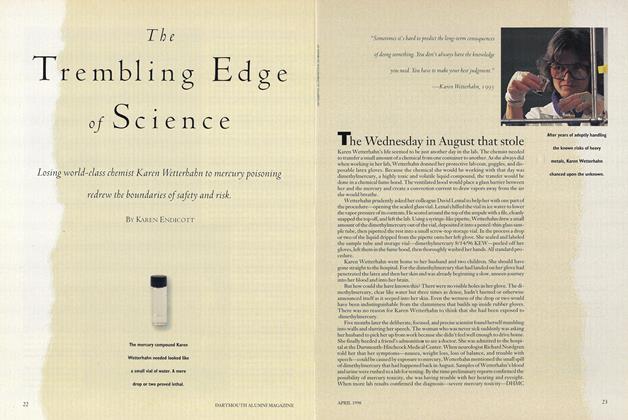

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

APRIL 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTransformation

MARCH 1995 By Richard M. Page '54 -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER