By night she washed dishes in Thayer for work-study financial aid funds. By day Kristine Taylor '89 was being lured away from premed sciences by a growing fascination with psychology. During sophomore summer she took a statistics course not everybody's idea of a good time. But this was Psychology Professor Jamshed Bharucha's stats course, which he enlivened by introducing his class to a new computer program that is useful for setting up psychology experiments. There was a catch, though. The software was full of errors. "Jamshed told us that we could use it if we were willing to correct the bugs," Taylor recalls. "I ended up asking him a lot of questions."

Her questions led the Rochester, New Hampshire, native to quit Thayer and take a job during junior year as Bharucha's student assistant.

Rarely has the term "work-study" applied so well to a student's endeavors. She conducted tests on introductory psych students for Bharucha's research on how the human mind processes music. She served as a control subject in the professor's experiments with a brain-damaged patient. And as she earned her wages, she explored the field of cognitive psychology, including neural networks. But her greatest payoff came from Bharucha's insistence on treating her work as if it were the start of a research career. For example, he insisted that she learn computer programming. "What good is a computer to you as an experimenter if you can't program it to do what you want?" he asked an initially reluctant Taylor.

and their naivite on paper led Taylor to conclude that computer models can be extremely useful in helping people to understand physics concepts. "I would like to give these results to physics professors to show them where people go wrong," she says. "Perhaps it would change the way they teach."

Her work with Bharucha has already affected other students. The professor made her a teaching assistant and had her give a lecture on her research for his introductory cognitive-psych course. In the days that followed "her talk, several students asked her how they, too, could become research and teaching assistants. She sent them to Bharucha.

Not surprisingly, some Dartmouth students and faculty members assumed that Taylor, who spent most of her senior year at her desk in the anteroom of Bharucha's office, was one of the Psychology Department's many graduate students. But grad school is elsewhere for her. This month she enters a program at the University of Oregon, a center of research in cognitive psychology. She has already arranged to work on motion perception studies with Jennifer Freyd, a leading researcher in the field.

Taylor says that graduate schools were impressed with her work with Bharucha's neural nets. But she credits her mentor not just the research with launching her career. "Jamshed got me fired up about psychology," she says, adding that she plans to become a college professor herself.

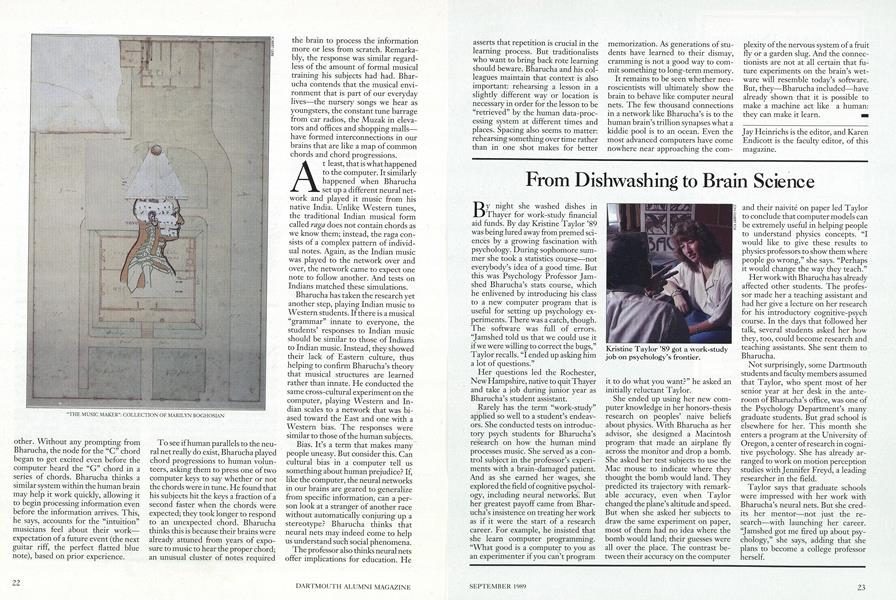

Kristine Taylor '89 got a work-study job on psychology's frontier.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

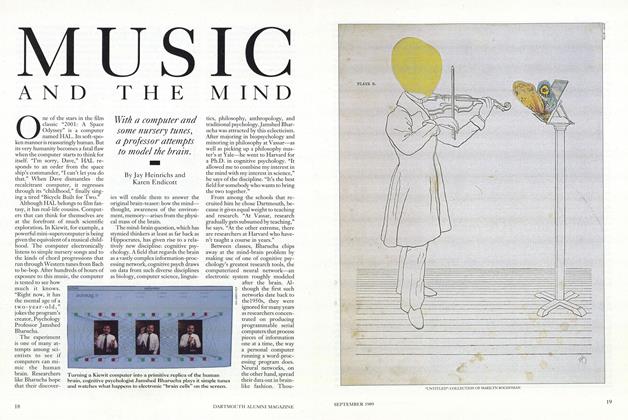

Cover StoryMUSIC AND THE MIND

September 1989 By Jay Heinrichs and Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureA Cure for Nostalgia: the Ultimate Comp Exam

September 1989 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

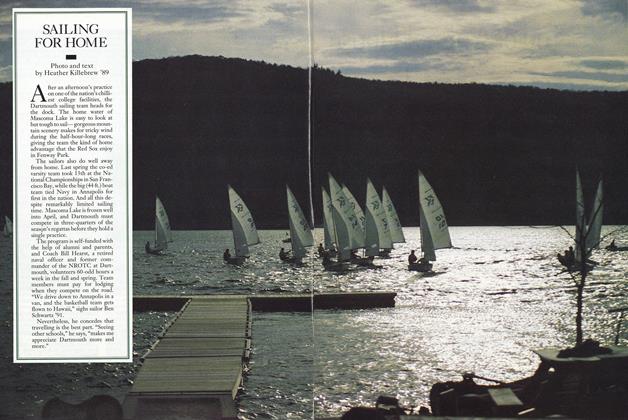

FeatureSAILING FOR HOME

September 1989 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureSon of Animal House

September 1989 By Ed. -

Article

ArticleThe man who wrote the movie returns to find brothers in slime.

September 1989 By Chris Miller '63 -

Article

ArticleDR WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1989