Neural networks are not limited to institutions like Dartmouth. Outside academia, the brainlike computer systems are being put to uses that non-neural programs can't match. A few examples:

• Airlines are beginning to use neural nets to allocate seats on flights.

• Security firms have devised systems that recognize individuals' handwriting or faces.

• Banks that have used neural nets to evaluate loan applications report fewer defaults.

• Neural networked electronic eyes look for parts defects in assembly lines.

• The Postal Service hopes one day to use the technology to read handwritten zip codes.

• The military has spent millions of dollars in hopes of revolutionizing target recognition, smart missiles, and self-navigating tanks.

And that's not all. Neural nets have also found their way into bond trading, oil drilling, linguistics, medicine, and the manufacture of products ranging from cars to fluorescent light bulbs. You can even try a neural network at home. A $99 program called Brainmaker (California Scientific Software, Sierra Madre) is made to be run on personal computers. Another PC neural net, called NeuroShell, can be had for $199 from Ward Systems Group in Frederick, Maryland.

But don't expect high-I.Q. computing for your money. Even the most advanced neural nets have a way to go before they become a match for human brains. According to the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, five years from now neural networks will be many times more sophisticated than today's versions but will only approach the complexity of a bee's nervous system.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMUSIC AND THE MIND

September 1989 By Jay Heinrichs and Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureA Cure for Nostalgia: the Ultimate Comp Exam

September 1989 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

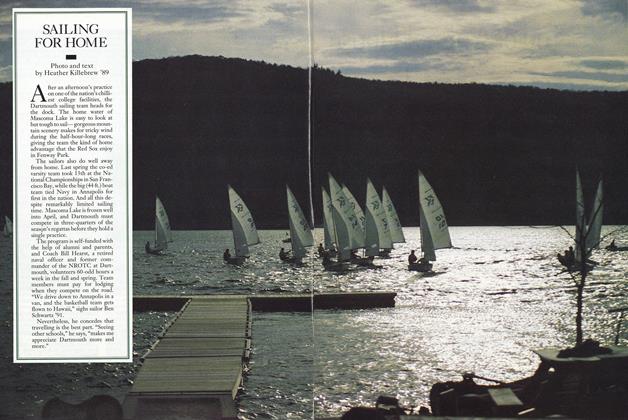

FeatureSAILING FOR HOME

September 1989 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureSon of Animal House

September 1989 By Ed. -

Article

ArticleThe man who wrote the movie returns to find brothers in slime.

September 1989 By Chris Miller '63 -

Article

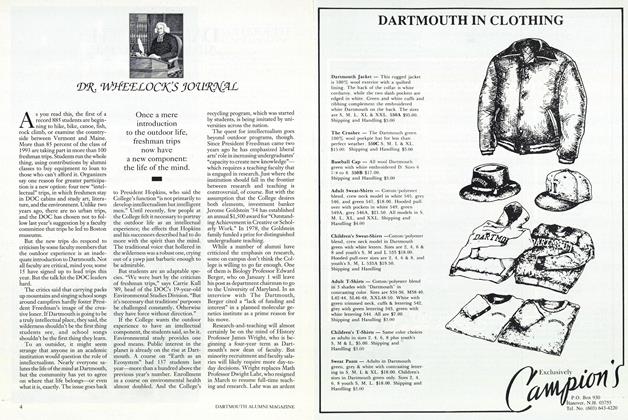

ArticleDR WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1989