The music still jumps—but you have to know where to listen.

Tune into jazz on the radio and chances are you'll hear some pretty mundane music. In this age of shirtsleeve emotions, pop jazz, and soft rock, a time when "easy listening" masquerades as improvisational music under the guise of "new age," it may seem that jazz has reached the end of the creative road. But—largely off the beaten commercial track—jazz musicians are still blazing provocative trails.

Modern jazz began almost 50 years ago in the after-hours clubs of Harlem as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, and others improvised music that was impolite and aggressive, urban and tough—though capable of being sensitive and tender in ballads. The name given to this new jazz matched its impact: bop! This was a controversial music which demanded that you sit down and listen; it was black music as art and black musician as artist.

Bop was difficult to play, and not everyone could deal with it—or wanted to. But bop begot other jazz styles. Miles Davis, drifting from bop in the 19405, unfurled the softer textures, unusual tone colors, and more complex arrangements known as "cool jazz." Harddriving, fiery "hard bop" flourished in the 1950s with such groups as Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, the quintets of Horace Silver, the Max RoachClifford Brown Quintet, and the first great quintet of Miles Davis.

Jazz styles proliferated in the 19605. There were tie "angry young men" Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, Max Roach, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Sam Rivers, Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane—who struck aggressive postures and refused to establish toe-tapping grooves. As in the bop era,"free jazz" black musicians were in the vanguard The sixties saw the second great quintet of Miles Davis and the seminaljohn Coltrane Quartet. The "cool, white, and intellectual" Dave Brubeck Quartet was the most popular small jazz group on college campuses. Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Sun Ra held court in the underground. The "soul jazz" of Cannonball Adderley, King Curtis, Jimmy Smith, the Jazz Crusaders, and Les McCann and Eddie Harris explored the roots of gospel and blues. Late in the decade, the Art Ensemble of Chicago rose out of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, and such white "jazz-rock" groups as Blood, Sweat and Tears and Chicago proved that rock with horns could swing.

In 1969 Miles Davis launched the "jazz-rock" or "fusion" revolution with a double album called "Bitches Brew. " His sidemen in the sixties became the leaders of the jazz-rock movement in the seventies and eighties: Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul, Wayne Shorter, John McLaughlin, Tony Williams, and Herbie Hancock. The seventies saw the "loft jazz" movement in New York, where this "new jazz" attracted attention in the performing spaces of the likes of Sam Rivers.

The Reagan years fittingly brought two conservative tangents: "neo-classical jazz"—exemplified by Wynton Marsalis, who not only played classical music brilliantly but sounded exacdy like Miles Davis in the 1960s—and "new wave," exemplified by mind-numbing performers Kenny G and Najee.

What's next? I don't think there will be any tidal waves capable of overwhelming other styles, just many smaller waves—some new, some old. Within the multiplicity of styles there is plenty of room for originality. Unfortunately, you seldom can hear the most creative jazz on the radio or buy it in your local record store. For the most part it is music outside the commercial mainstream: underrecorded, poorly marketed, existing beyond the bandwidth of normal airplay. But it does exist, and is well worth the search.

For starters, here are some of the more notable jazz recordings of the last decade. All can be special-ordered from your local record store or from the Bose Express Music Catalog (50 West 17 th Street, New York, NY 10010; telephone: phone:1-800/233-6357). Many of the musicians below have performed with Dartmouth's Barbary Coast. All will grab your attention.

of the struggle for social change.

Don Glasgo goes far the spontaneity,improvisation, and rhythm of jazz.

As director of Dartmouth's student jazz ensemble, the Barbary Coast, adjunct professor of music Don Glasgo serves as a catalyst for the creative alchemy that is jazz. Coaxing students to the improvisational edge, he turns budding musicians into jazz performers. The method behind Glasgo's magic is to teach students about style and rhythm largely through listening to the work of different artists. "Jazz is an oral tradition. You leam by hearing," he says. "One of the most gratifying results of all this effort is seeing students become enamored of great artists they weren't aware of before. I love teaching them to respond to creative music." Then comes his.alchemy: helping students put that response into their performances. "Students often solo for the first time with the Barbary Coast," he explains, "'lo have the courage to express their own voice in a solo, they need unwavering support. I try to provide an atmosphere of encouragement and understanding. It's a delicate, but rewarding task." Glasgo's affinity for jazz goes back to his college days at Ohio University and the University of Illinois. While studying classical music, he found himself more and more attracted to jazz, particularly jazz composition and arranging. Because there were few jazz studies programs in academia at the time, Glasgo earned a bachelor's and master's degree in theory and composition. After moving to Hanover in 1974, he foresaw his Dartmouth calling at, a Barbary Coast concert. "The Coast was student-directed then," recalls Glasgo. "Though that succeeded for them in the past, in 1974 they needed some guidance." He offered his services and has been with the ensemble for 14 years. During that time he has pursued doctoral studies in ethnomusicology at Illinois; taught courses on jazz history and world music; taught himself jazz piano; and founded "Jazzlines," a newsletter that reaches more than 700 jazz enthusiasts. One of Glasgo's joys has been bringing in major guest artists for the Barbary Coast's Winter Carnival concerts. He recounts his favorites: "Dexter Gordon, by reason of sheer presence. Max Roach, by virtue of his generosity and commanding musicianship. Slide Hampton for his outstanding arrangements and virtuosic 'trombonisms.' Sun Ra, for being Sun Ra. And Lester Bowie, from whom I learned the most musically—and he was a lot of fun!" Heather KiUebrew ’89

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

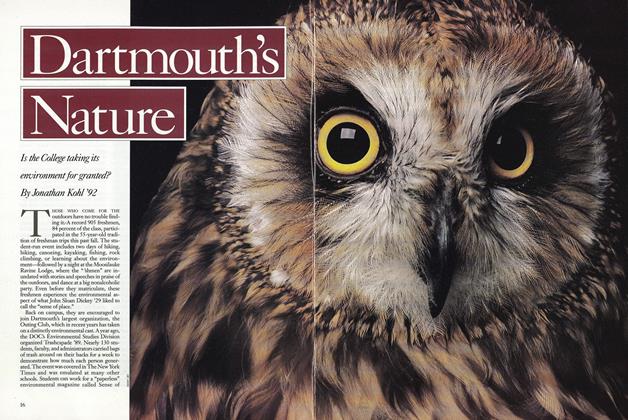

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Nature

December 1990 By Jonathan Kohl ’92 -

Feature

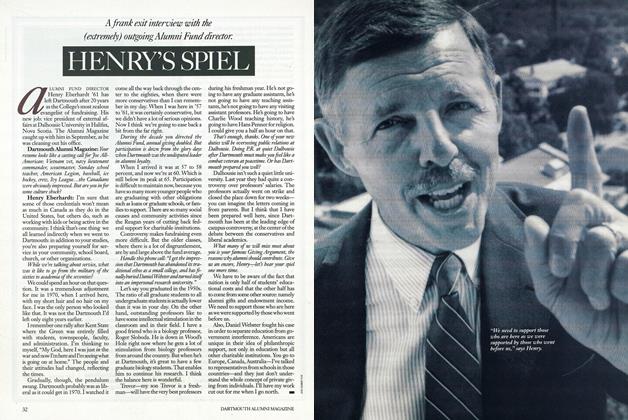

FeatureHENRY’S SPIEL

December 1990 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK’S JOURNAL

December 1990 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleThe Case Against the Dartmouth Review

December 1990 By George B. Munroe -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

December 1990 By Michael H. Carothers