In the early fifties, John Sloan Dickey 29 had thechance to create virtually a whole new faculty.What he did led to the Dartmouth of today.

JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29, THE TWELFTH president of Dartmouth College, once said his term fell into three periods of roughly eight years each. In the first such period there was litle he could do that was new. The second period was one of rapid change, perhaps unparalleled in the history of any mature institution, and the third was one of consolidation. I was fortunate to witness the last two periods as a member of the faculty. These were the years 1953 to 1969. They have a lot to do with the College you see today.

He faced a second, more subtle problem as well. If you ask a college president what kind of faculty he or she looks for, you're likely to get a glib answer: "All faculty members should be outstanding teachers and truly eminent in their field." Of course, the statement is always sincere, but we would be liars if we claimed to succeed with every member—there just aren't enough top teacher-scholars to go around. Therefore, although good institutions are fortunate to have several who are outstanding in both areas, presidents have to compromise. And how they compromise shapes their institutions.

A great deal has been said about the differences between Harvard and Dartmouth. The most visible is that Harvard has some very large graduate schools. But the most significant difference for undergraduates is how the faculty is chosen, and what it sees as its priorities. Harvard rightly prides itself on having a large number of world-famous, highly eminent people on its faculty. It does not hesitate to appoint such people, even if they happen to be poor teachers and hate freshman classes. Dartmouth will pass up some of these same eminent people if they are poor teachers, and that is a fundamental difference between the two institutions. I used to say to students, "Don't look at the names in the catalogue. Find out who teaches the freshmen."

President Hopkins certainly espoused this philosophy, but he went a step further. He once gave a famous speech in which he questioned the Ph.D. as the appropriate degree to qualify people for teaching at the college level. "To a point, I can understand his qualms. I have personally known many Ph.D.s who were absolutely lousy teachers. But that is not the whole story, and that is where John Dickey's second problem came in. While President Hopkins recruited a number of faculty who were eminent in their fields, many were not. And even eminent professors don't always remain active. A superb teacher at age 30 may be hopelessly out of touch by age 60. Eventually, scholarly work became the exception rather than the rule. I think the Mathematics Department is a textbook example.

Math during the Hopkins years of the 1920s was truly outstanding. I am told by senior colleagues at other institutions that it ranked among the ten best mathematics departments in the country. But during the early 1930s, one key member died young. Another left for a sister institution. And still others who had been active in mathematics became inactive. Robin Robinson '24 remembers joining the department as its youngest member in 1929. He served for many years with distinction and became one of the College's great registrars. What he didn't realize was that he would remain the youngest member of that department for 25 years. And mathematics is very much a young person's field.

Then, in the early fifties, John Dickey suddenly faced the retirement of most of the tenured faculty in a relatively short time. He was determined to build a new one that would be different not completely different, because he prized outstanding teachers just as much as President Hopkins didbut one in which members remained active in their fields. The phrase we heard over and over again from John Dickey was "teacher-scholar." Sometimes we got very tired of hearing it, and it is only in studying history that we realize why John made such a point of it: he wanted for Dartmouth the best of both worlds. He wanted people who were outstanding both as teachers and as scholars.

I don't know how much of that legend is true, but the young political scientist, Donald Morrison, did become dean of a quite elderly faculty at a ridiculously young age. He eventually became the first provost of Dartmouth College. The history of this period of rapid change is of a collaboration between John Dickey and Don Morrison. They made a great team, because the president can set the general tone of the institution and give it direction, but the dean and the provost will lead the recruitment effort.

When Morrison was made dean, I was still on the Princeton faculty. I was happy there; my wife, Jean, and I were making plans for building a house and starting a family, and I had every expectation in the world of spending the rest of my life at that university. And then a telegram arrived. "Can you have lunch with me Friday?" it said. It was signed by some dean of the faculty of Dartmouth College. I turned in surprise to Jean and said, "Where is Dartmouth College?"

I would learn the answer to that question rather well later on. But first I had lunch with Dartmouth's dean, who said he had come to persuade me to leave Princeton. I quickly said to him that there was absolutely nothing he could do to persuade me. Naturally, I was wrong.

Dean Morrison said he wished to put before me an opportunity: to come into a department where only three members would be left by the time I arrived, and to build it backup from scratch. I could not resist that challenge. Thus I became one of the first senior appointments that John Dickey would make as president. (I use the phrase "senior appointment" in the technical sense, in that I came as full professor and as chairman-designate. I certainly was not senior in age, being only 27 years old at the time. I was lucky that, in the midst of the painstaking research Don Morrison had done on me, someone got my age wrong and thought I was 31. If Don had known my true age, Dartmouth's history might have turned out differently)

I learned many years later, after becoming close friends with Don, how I came to be invited. The Math Department happened to be the first one where a huge number of retirements would occur, so John Dickey said to Don, "Let's make an example of it." He invited a visiting committee of some eminent mathematicians. They spent two or three days on campus and wrote a report that Don was careful not to show me until it could have no possible influence on my work as chairman. That is because, after looking at all the facts, the group concluded that it was not possible to build a first-rate math department at Dartmouth. Instead, the group said the best we could do was to build a department that would be distinguished in teaching. And perhaps we could become strong in a not-very-competitive area in mathematics; they suggested the history of mathematics.

Remember, Dean Morrison was a political scientist claiming no special expertise in mathematics. Still, he read the report, shut it in his desk, and said, "What do I do next? I'm certainly not going to do that." Instead he asked Dartmouth's mathematicians: "Which school has the strongest math department?" At that moment the best one happened to be at Princeton. Don went there and asked the chairman, "How do I build a math department?" The chairman replied, "You can't build a math department. You're not a mathematician. Your job is to identify a promising young mathematician, bring him to Dartmouth, and then give him a completely free hand in building a department."

What happened with Dartmouth's Math Department was repeated throughout the entire institution. Each time, the attempt was made to bring in one or two key people and then let the department take off on its own. After a decade of this, the changes were decisive.

When I first came here, the Math Department was housed on the top floor of Dartmouth Hall. Next to us was a department (I won't identify it) of very nice gentlemen. They were conscientious teachers, but we found one thing terribly odd about them: all the offices were empty after noon. The professors would come in and teach their classes, but there was no other professional activity going on in that department at all. We in Mathematics, on the other hand, were a bunch of Young Turkswe were quite likely to be in our offices at midnight. Very strange.

The committee wanted to know how we could add a course without hiring another faculty member. "Who's going to teach it?" the members asked. "Professor X will teach it," I replied. "All right," they said. "That means he has to drop some course he taught last year. Who is going to teach that one?"

I was confused. I recited the courses that Professor X was teaching in the current year and those he was scheduled to teach in the next year and—although this wasn't typical even for us—it happened that no two of the courses were the same. The committee looked at me as if I were mad, and that's when I found out that most faculty members at the time taught exacdy the same courses year after year after year. Don Morrison once noted in a quite public forum that in some courses the lecturenotes had not been changed for 20 years. That era ended with Dickey.

With the change in the faculty came a change in the quality of students. And here I want to be very specific. I liked Dartmouth students from the moment I arrived. When I compared the qualifications of Dartmouth and Princeton students, I found that the average Dartmouth undergraduate matched his counterpart in Princeton. We also had a few students who were as good as the best students at Princeton. The problem was, we had very few of them—statistics showed that Dartmouth was simply not getting its share of the best. Furthermore, our outstanding students said they rarely came because of the faculty's reputation; they came because of Dartmouth's many other attractions.

It took a lot of work to get the word out to students, parents, and school counselors. It took strange collaborations—the football coach, Bob Blackman, and I became good friends. I helped him recruit good football players, and Bob recruited a number of outstanding mathematics students who never played football. We also recruited some darned good math students who played football. We were proud when a co-captain of the team was an honors major in mathematics. This is a far cry from the college players you see on television who are majoring in "undergraduate studies"—whatever that is.

Dartmouth's ability to attract outstanding students improved noticeably during the sixties, and it improved even more during the seventies. This was important, because there is a symbiotic relationship between the faculty and its students—particularly the top students. I can speak to this personally, as someone who has taught more than his share of huge lecture sections that represented a cross-section of the student body. I was happy with these students, but there is a special thrill in recognizing a small number who are exceptionally talented. It takes very good faculty to attract them. In return, a reasonable number of outstanding students is terribly important in retaining the best faculty.

Let me briefly look at some other changes. One that came, was glorious and died, was the Great Issues course. It was a success for many years, and I've heard testimony from endless numbers of alumni that it meant an enormous amount to them. In spite of that, the course died in the sixties. My guess as to its demise is this. When it was first put in, it was so innovative—it was truly unique in the nation—that the College could attract the greatest stars in all fields to come here and lecture to the entire senior class. As time passed and some of the novelty wore off, the College appears to have been forced to turn to some secondstring speakers, and eventually to some thirdstringers who couldn't keep the attention of the entire senior class. Remember, this was the sixties. I happen to love the students of the sixties—they had many good attributes but being polite to boring lecturers was not one of them.

A second highlight of the Dickey era, and one where Dartmouth did not receive enough credit, is the distributive requirement. I happen to think we have one of the best in the country. It's not a specified list of required courses but a rule that students cannot be too narrow, that they must sample the humanities, the sciences, and the social sciences. All such requirements were under enormous attack by the students of the sixties, and most institutions compromised. One Ivy League institution gave in completely; we did not. Of course, much of the credit belongs to the faculty, which votes such requirements. But John Dickey was right out in front, arguing against compromising our standards. His words stiffened the faculty's backbone. I was quite angry when, a couple of years ago, Harvard got much media acclaim when it toughened its requirements. A Dartmouth alumnus asked me how Harvard's wonderful change compared with what we had at Dartmouth. I responded by saying that Harvard was getting all the publicity for going back to what Dartmouth had never given up.

Then there was John Dickey's move on discrimination. His ultimatum to the fraternities—giving them ten years to remove all discriminatory clauses from their charters or else go local—made headlines even in England, where I happened to be at the time.

But I don't want to leave you with the impression that all changes come from the administration. If you bring in the right faculty, they are going to come up with initiatives, probably many more than an institution can take. Therefore the administration's role is to support the most promising ones. Of the many such changes over those 16 years, two got the greatest public recognition—and, according to a survey, did the most to make Dartmouth even more popular with prospective students. The first of these is the Freign Study Program. The faculty initiated it, and it is the best of its kind in the nation. Some 60 percent of all Dartmouth students now spend at least a term overseas in programs of high quality.

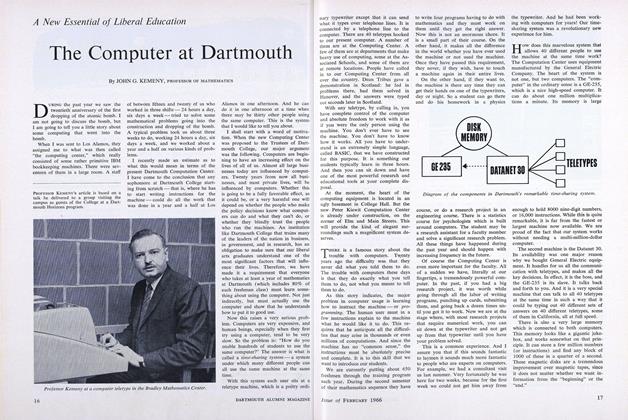

The second area is computers. Dartmouth was a most unlikely place to take a lead in this field, which requires expensive hardware. We substituted ingenuity for money a good tradeoff—and in 1964 became the first institution where every student, every faculty member, had a chance to use a computer freely. I was once asked at a professional meeting how we managed to come in first, even though M.I.T. had started building a large time-sharing system a year before we did. My answer was that M.I.T. had hired professionals, while we had hired undergraduate students.

I want to mention one controversial decision of that period. This was the launching of Ph.D. programs at Dartmouth College. There's never been a question that the undergraduate college was the number-one priority, and yet we tend to forget Dartmouth's history of having pioneered in graduate education. Let me remind you that we have the fourth-oldest medical school in the country. It goes back to the eighteenth century. We may have been founded by a Yale man, but, as President Dickey once rubbed in to Kingman Brewster, the Yale Medical School was founded by someone from Dartmouth Medical School. We have one of the oldest graduate civil engineering schools in the country, and we have the oldest school of business administration.

Graduate education is not strange to our history. But before the late fifties, the Trustees had drawn a line at not having Ph.D.s. Then in came the Young Turks, who clamored for some modest programs. Skeptics said to us, "If you didn't like to teach undergraduates, you should never have come to Dartmouth. You know .what the number-one priority of the institution is." Our answer was a question: "Would a top faculty member spend 30, 35, or 40 years of a professional career without ever teaching an advanced course?" It is not that undergraduates aren't bright enough to take such a course. It's just that many fields, such as mathematics, have to be taught sequentially. Undergraduates—even the best ones—never get quite to the edge of knowledge. Our argument was to give us the stimulation of teaching advanced courses, and the supervision of graduate theses—which is a good way of keeping faculty up to date with their fields.

There were safeguards built in. The number of graduate students in Arts & Sciences was limited; to this day, we are nowhere close to that limit. As a matter of fact, when I became president, I tried moving on this. I felt badly that none of the Ph.D. programs was in English. I got a major foundation grant; a committee planned a good Ph.D. program in comparative literature; and then the bottom dropped out of the job market. At its last meeting, the committee said, "If we go ahead with this program, we're going to train unemployed Ph.D.s in comparative literature." We decided not to go ahead.

A decision made late in the Dickey presidency was to return the Medical School to a full four-year program. When I heard about it, I stormed into the office of Leonard Rieser '44 and said, "This is the stupidest decision I ever heard." By the mid-seventies, I had changed my mind. If the Trustees had not made the decision, the health-care system here would have become second- or third-rate-ruining health care not just for the Dartmouth community but for a large part of northern New England. Last fall, I happened to be lying in the hospital after a recent operation. I was terribly grateful that the Trustees had decided not to listen to what I had once said on the subject.

In retrospect, what can we say about the Dickey faculty? First of all, it has been intensely loyal to the College. There were some losses. A small number—much smaller than at our sister institutions—left. Some died, of coarse. There were some very painful losses that's when outstanding faculty members decide to become administrators. (Think about that one!) But most of the faculty devoted the bulk of their professional lives to Dartmouth College and stayed here until retirement. They have received extremely high marks from students, both for the quality of teaching and for devotion to the student body. Pick up almost any guidebook for secondary-school students and look under "Dartmouth" the faculty's dedication will be singled out for praise.

John Dickey also got his wish. This faculty has remained active in its professions, carrying out scholarship and research. Many departments became major forces of innovation, which helped the reputation of the institution, and, in many cases, had a national impact.

That is the legacy left to us by John Dickey and by Don Morrison. It is a proud chapter in the history of Dartmouth College. MM

Students need only look aroundthem to find one of the College'smost underrated strengths—assetslike its cabin on Reservoir Pond.

Dickey brought in thefreshest of blood byapproving the hire of a29-year-old Princetoniannamed Kemeny to headup Mathematics.

Instead of beingcanned, the story goes,Morrison was deaned.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

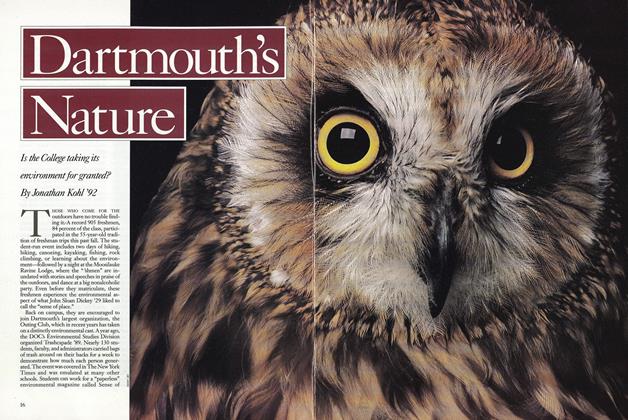

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Nature

December 1990 By Jonathan Kohl ’92 -

Feature

FeatureHENRY’S SPIEL

December 1990 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK’S JOURNAL

December 1990 By E. Wheelock -

Article

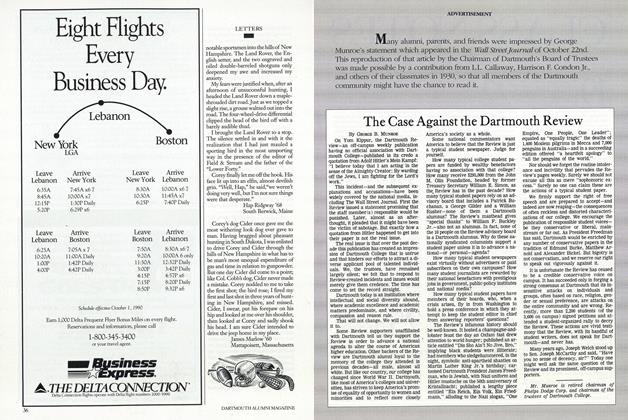

ArticleThe Case Against the Dartmouth Review

December 1990 By George B. Munroe -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

December 1990 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

December 1990 By Fred Carleton

John G. Kemeny

-

Feature

FeatureThe Computer at Dartmouth

FEBRUARY 1966 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleThe road less traveled

DECEMBER 1971 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleI was enormously moved

April 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

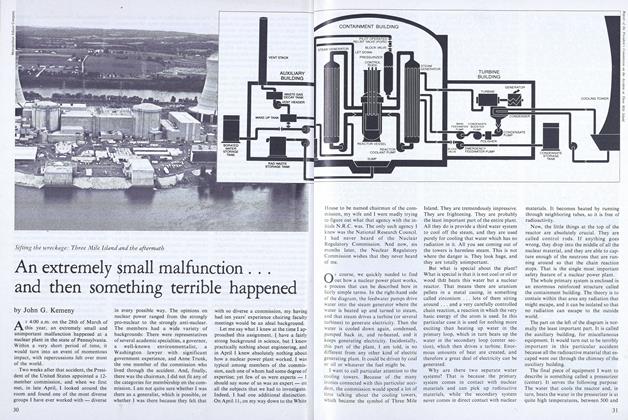

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

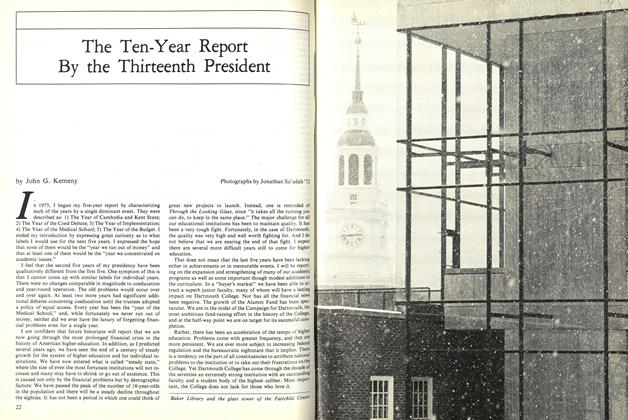

Cover StoryThe Ten-Year Report By the Thirteenth President

June 1980 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Feature

Feature"The Real Business"

June 1955 -

Feature

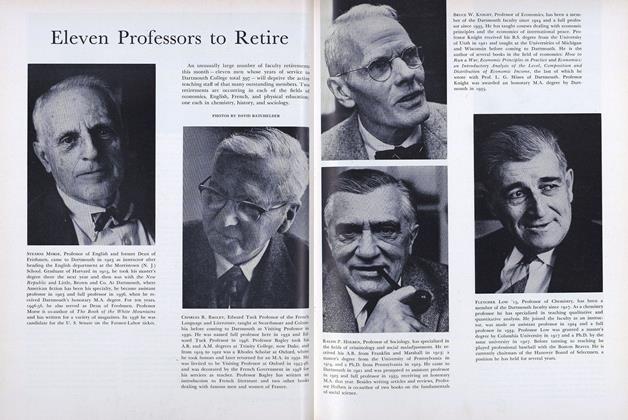

FeatureEleven Professors to Retire

June 1960 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

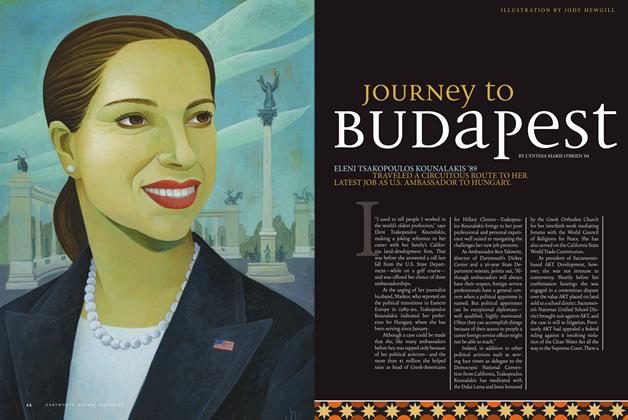

FeatureJourney to Budapest

Nov/Dec 2010 By CYNTHIA MARIE O'BRIEN ’04 -

Feature

Featureclassnotes

MARCH | APRIL By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

FeatureNuances

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Oz Griebel '71