Can a hockey team win without reruiting Canadian talent or using bruteforce? For the Dartmouth women's hockey team the answer is yes. Thanks to homegrown talent and a no-check rule in the women's game, Dartmouth's female hockey players have emerged as a force in the Eastern College Athletic Conference. The team is certainly one of the most idio syncratic. The skaters and their coach, George Crowe, consume more than 80 pieces of bubble gum per game. Last year they chewed their way to a 17-9-2 season and edged out Harvard and Cornell in overtime victories to win the tournament. But there is a good deal more to this success story than pink, squishy candy.

Winning the Ivy title is nice, but winning the Ivy League tournament is nicer because the tournament winner earns an automatic berth in the ECAC championships. Anchored by captain Kelley Coyne '90 in the net, the team wants to win the Ivy tournament again and challenge the dominance of the scholarship-granting ECAC powerhouse trio of Providence, New Hampshire, and Northeastern. Last year Coyne was crucial to the team's success. With her dazzling .931 save percentage, the number-two-ranked Ivy goalie held the opposition to an average of 2.02 goals per game.

At the other end of the rink, top scorers Judy Parish '9l and Lori jacobs '92 remain the key to the Green offensive attack. Parish, who excels at both forward and defense, was named first-team All-Ivy as a sophomore and ECAC rookie of the year as a freshman. She has plastered her name all over the Dartmouth record books with most goals by a defenseman (single-game, entire season, and career) and most assists by a defenseman (single-game and entire season).

This level of competition is extraordinary considering that women's hockey was virtually nonexistent, even in Canada, back in 1979 when the sport made its first appearance at Dartmouth. Crowe, who was the men's coach at the time, recalls that the talent pool was quite small and inexperienced; only half the fledgling team had ever played before, and the rest were converted figure skaters. Now in its eleventh season, the Dartmouth team has emerged as a force within the Ivy League, which in turn is becoming competitive with the scholar ship-gran ting schools. "It used to be you'd play them and get beaten by eight or nine goals," says Crowe. "Now there's a little more parity between the top three and the Ivies."

Even so, the number of experienced women players remains small—most women don't pick up the sport until high school. Goalie Coyne is an exception. The Cropseyville, New York, native started playing at age four. She had a big brother for inspiration. "I always used to follow him around and do everything he did. He hated me for it," she laughs. More typical is the experience of forward Caroline Horn '92, who says her parents did not allow her to play until she enrolled at Choate Rosemary Hall. "It was sort of the 'daddy's little girl' syndrome," she recalls. At boarding school, however, things began to change—hockey was in. "It was really the sport for girls," Horn says.

Not all schools have that sort of attitude. In an attempt to increase the pool of players, Crowe has founded a one-week summer hockey camp in Hanover, which drew more than 150 skaters last year.

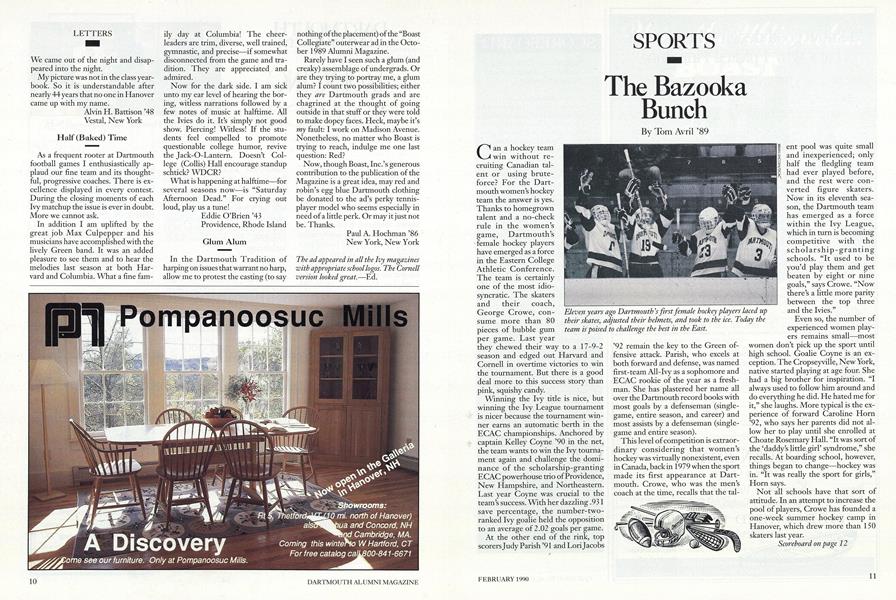

Eleven years ago Dartmouth's first female hockey players laced uptheir skates, adjusted their helmets, and took to the ice. Today theteam is poised to challenge the best in the East.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

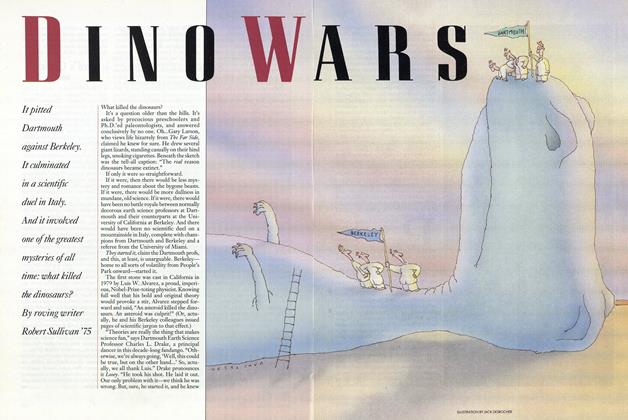

Cover StoryDino Wars

February 1990 By Roving Writer Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

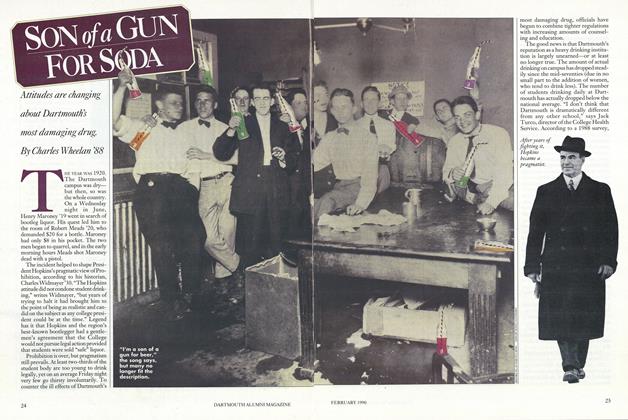

FeatureSon of a Gun for soda

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureIf You Thought the Comps Were Hard, Try This Quiz

February 1990 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

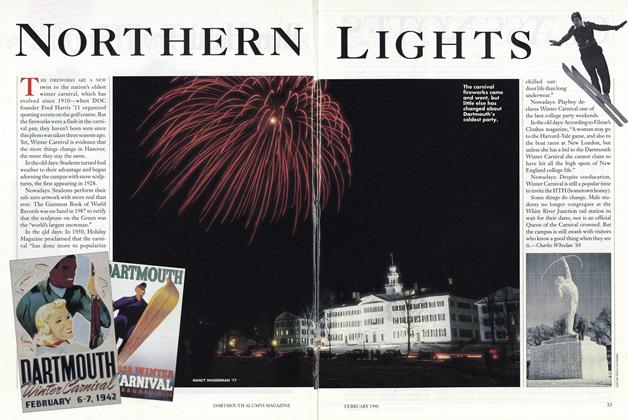

FeatureNorthern Lights

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

February 1990 -

Article

ArticleTHE ETHICS OF THE BOMB

February 1990 By Professor Walter Sinnott-Armstrong