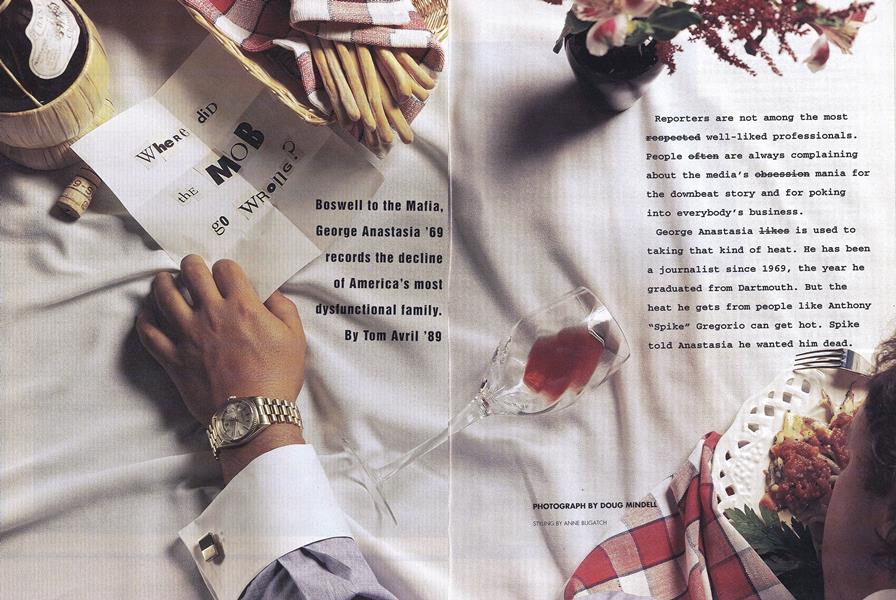

Boswell to the Mafia, George Anastasia '69 records the decline of America's most dysfunctional family.

Reporters are not among the mostrepected well-liked professionals.People often are always complainingabout the media's obsession mania forthe downbeat story and for pokinginto everybody's business.

George Anastasia likes is used totaking that kind of heat. He has beena journalist since 1969, the year hegraduated from Dartmouth. But theheat he gets from people like Anthony"Spike" Gregorio can get hot. Spiketold Anastasia he wanted him dead.

ACTUALLY, SUCH A DEATH THREAT IS A RARE hazard of Anastasia's beat. He covers organized crime for The Philadelphia Inquirer. That means he waits with the cops outside of Mafia funerals so he can swap information and watch who goes in and out of the church. It means he gets phone calls at odd hours from guys you wouldn't want within miles of your little sister. It means that the former Ivy League rugby player and espresso-sipping French major hangs out in scary neighborhoods where small slights—let alone unflattering newspaper stories— are taken seriously.

It means he gets Christmas cards from some unusual people. There was the one he got last year from Junior Moran, a mob associate now on death row for the murder of a local union boss. The card read: "Peace on earth, goodwill to men."

Because of his many interesting acquaintances, Anastasia had the best seat of any reporter in the country for what was arguably the bloodiest mob power struggle in U.S. history—a five-year battle that resulted in the murders of 28 Mafia members and. associates. Anastasia saw the rise and fall of the ruthless gangster Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo, the first American mob boss ever convicted of first-degree murder. Anastasia has published two successful books on the subject: Blood and Honor, an account of Scarfo's downfall; and Mobfather, a poignant description of a family that was torn apart during the struggle.

In a profession that is not known for reserved manners, Anastasia has an easy-going, earnest demeanor with just a hint of the South Philly tough guy. "He can put gangsters at ease, he can put cops at ease," says Fred Martens, executive director of the Pennsylvania Crime Commission, a non-profit fact-finding group. "Not that there's that much difference."

These social skills were clearly put to good use in Bloodand Honor, which was largely based on colorful stories related by Nicholas "Nicky Crow" Caramandi. Nicky Crow was a wiseguy who flipped and went into the Program because he was afraid of getting whacked. (Translation: Caramandi ratted on his fellow mobsters because he was afraid they'd kill him.) Now the Crow is cooling his heels in the Federal Witness Protection Program—"somewhere warm," according to Anastasia, who adds that he is not sure where that is exactly and doesn't want to know.

What Anastasia does know are details so sensitive that sometimes the police come to him for information. "He knows what kind of toothpaste they I use, what kind of toilet paper," jokes Justin Dintino, former superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. He adds seriously: "I'd gladly hire him as an investigator."

Much of the information comes from a group of seven or eight mobsters either flipped, been convicted, or both. Some call Anastasia's office. Others, like Moran, send Christmas cards. They like the work that Anastasia does, and they like being in the headlines, so they call him to get in their side of the story. Most are friendly—such as Nicky Crow Caramandi, a Philadelphia native who dropped out of junior high but makes up for it with his street smarts and charm. "'I guess we're friends," Anastasia says of Nicky Crow, with a shrug. With Spike Gregorio, things are a little more prickly.

IT WAS A REGULAR SEPTEMBER day in 1991 at the suburban New Jersey offices of The Philadelphia Inquirer—a standard office complex with modular furniture, acres of parking lots, and a monstersized mall just next door. Anastasia picked up his phone when it rang. It was Spike, who, it seemed, was very unhappy.

A small-time con man, Spike used to handle the cooking and housekeeping at Scarfo's Ft. Lauderdale hacienda. He had a story to tell, and he wanted George to tell it for him. George, perhaps unwisely, had said no. Blood andHonor was due out later that year, and Spike had nothing new to add to the tale. The book came out in the fall, with no contributions from the attention-starved mobster. On that day in September, an unhappy Spike called—collect—after having had a few too many drinks.

"I'm going to get a hatchet and crack you in the head. I'm going to shoot you between the eyes. I know where you work," Spike told Anastasia, who recalls that the phone call lasted about 20 minutes. When Spike was done, Anastasia dialed the FBI.

Which doesn't mean he admits to being scared on the job. "Concerned," maybe, but not worried. If you ask Alan Hart, a private detective who does work for attorneys representing the Mafia, that kind of attitude might be a bit foolish. "Some of the characters he's written about, he damn well should've been scared on occasion," Hart says. Anastasia's wife, Angela, agrees. "At first when we had people in organized crime calling us at home, I was a little concerned. George always tells me not to worry. But I do worry."

The Spike incident turned out fine, actually. The mafioso had just gotten a little hot under the collar, that's all. The death threat was a momentary little act of drunken rudeness, and Spike felt sorry afterward. A few days later, sobered up, Spike called George back. He wanted to apologize. Which was a very good thing. Spike was a Mafia "associate," just a step down from full-fledged membership. To qualify for membership you have to kill somebody. It is not a bad idea to treat a threat from such an aspirant seriously.

USUALLY, ANASTASIA'S DEALINGS WITH THE mob are not quite so tense. Some of the younger hoods tell Anastasia, in less than genteel language, to get lost. Others like to give him dirty looks. But in general the South Philly native is accepted, particularly by the older mobsters who still abide by their own peculiar code of honor. In their book he is a guy from the neighborhood, someone who can be trusted. "He projects the image of a real knowledgeable street kind of guy," says Hart, the gumshoe. The mob knows George has his job to do, and it doesn't hurt that he is about as thoroughly Italian- American as you can get. He is the grandson of Sicilian immigrants, and he married a woman whose grandparents came from Sicily and from near Rome. Anastasia is proud of his heritage, and he revels in soaking up the ethnicity of Philadelphia and its colorful neighborhoods. His favorite story involves an Irish police officer who, during testimony before a parole board, had to explain the mob's customary European-style greeting of a kiss on both cheeks. "It was classic testimony," Anastasia says. "An Irish cop explaining a Sicilian custom to a group of WASPs sitting on a parole board."

His Italian heritage gets him into trouble with some of those who share that background. They resent all the hype about the Mafia, as if the mob were Italy's sole contribution to society. Anastasia's own mother-in-law refuses to see the Godfather movies.

Anastasia has a different take on the situation. He sees himself not as a traitor to his heritage but as a sympathetic observer. And, indeed, he is careful in his writings to point out the positive contributions of the vast majority of his ethnic group. "I thought if anyone was going to write about organized crime, basically an Italian-American mob, it ought to be an Italian-American," he says, adding: "I don't think you can live your life worrying about people who buy into stereotypes, no matter who you are. Stand up. You are who you are, and screw anybody else. That's my attitude. I understand where some people come from when they say that, I just don't buy into it."

Most of Anastasia's subjects are doing little themselves to change the stereotype. Their very nicknames, which they take seriously, sound like the product of a politically incorrect novelist: Ronald "Cuddles" DiCaprio. Frank "Faffy" Iannarella. Joseph "Skinny Joey" Merlino. Vincent "Al Pajamas" Pagano. These are real guys, and they actually call each other by those names.

ANASTASIA HIMSELF HAS A NICKNAME, ALBEIT not one bestowed on him by the hoods he writes about. His buddies at Dartmouth apparently decided that "George" didn't sound Italian enough. So they named him "Vito." Those sensitive Dartmouth boys.

It was at Dartmouth that Anastasia got a taste for newspapering. That was during the pre-Watergate period, before every starry-eyed punk with a pen wanted to become the next Woodward or Bernstein. During French foreign-study programs in Montpelier and Toulouse, Anastasia would buy the International Herald Tribune every day and read it at a cafe while sipping cafe au lait. That got him interested in the business, and upon graduation he talked himself into a job at the Woodbury Times, a local newspaper in South Jersey. He married Angela, and soon came daughters Michelle and Nina. (Michelle graduated from Rutgers in 1993, and Nina is a student there.) George went on to the Courier-Post in Camden, New Jersey, before joining the Inquirer in 1975. In 1976 he covered the Atlantic City referendum that legalized gambling. Ultimately, that led to a fulltime beat covering organized crime, along with an insider's knowledge that is legendary among law-enforcement circles. "Sometimes I think he's in with them, like a fly on the wall, his information is so accurate," marvels Richard Zappile, chief of detectives for the Philadelphia Police Department.

That knowledge comes not just from tips but from an acquired sense of history—a sense tinged with apparent regret over the change that has come over the mob in recent years. Gone, to a certain extent, is the curious code of honor that existed among the oldtimers, many of whom were born in Italy. They may have been murderers, extortionists, and con men, but at least they didn't rat on each other. Since 1986, however, more than two dozen mob members and associates have flipped in the United States—a virtually unheard-of practice in the past.

Anastasia blames the change on kids these days. The mob's current troubles began with the murder of Philadelphia kingpin Angelo Bruno on March 21, 1980. The younger generation of hoods had grown impatient with the "Docile Don's" ban on drug dealing; he himself was suspected of skimming proceeds from dealers while keeping his own troops out of the action. And his seeming reluctance to get on the gambling gravy train in Atlantic City was too much for the impatient youngsters to bear. Bruno's reign ended with a shotgun blast to the back of the head as he was being driven home from a restaurant. To this day no one knows exactly who carried out the murder. The honors probably go to a few of the younger Philadelphia family members, who had the backing of some New York mobsters.

Bruno was succeeded by his second in command, Phil "Chicken Man" Testa. He lasted only a year before he was blown up by a nail bomb. Testa's successor: Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo, a man so ruthless, violent, and unpredictable that he shocked even his fellow mobsters. "Scarfo was a mob boss for the eighties," Anastasia wrote in Blood and Honor. "A greedy, ruthless despot whose family coat of arms could have been a pair of crossed .357 Magnums mounted on a blood-red shield embossed with the words 'Kill or be killed.'"

Scarfo's violence and paranoia proved to be his downfall. He offed 14 of his closest associates and was turning against still others when they began to squeal to save their own skins. Phila- delphia capo Thomas "Tommy Del" DelGiorno went to the FBI. Several days later, so did another high- ranking mobster, Nicky Crow himself. During the relatively gentle days of Angelo Bruno, mafiosi were often allowed to live when they screwed up Tommy Del anc the Crow knew they had no such luxury And so they turned on Scarfo, and on the family with him. The testimony sent the entire Philadelphia leadership to life imprisonment —except themselves. Caramandi and DelGiorno each got light sentences.

The mass convictions led to more flipping. Mafia turncoats eventually gave prosecutors ammunition to go after the mob in other cities, including New York's infamous Genovese family led by the "Dapper Don," John Gotti. But the story doesn't end there. The breakdown in the Mafia's own sense of morality has resulted in a series of well-publicized murders and mob-style takeover bids that continues to keep Anastasia extremely busy, and sometimes almost frenetic.

IN JANUARY 1993 A SOUTHERN Californian weightlifter named Rod Colombo was found slumped in the front seat of a car in Audubon, New Jersey. He had been shot three times in the back of the head. Colombo, who favored fine clothes and highly polished Italian loafers, was a suspect- ed mob associate and drug courier. The motive for the shooting was unclear, so Anastasia flew out to Colombo's remote hometown of Post Falls, Idaho, to track down his roots. But while Anastasia was out west, Mario "Sonny" Riccobene was found dead in similar fashion in the parking lot of a South Jersey diner. In that case, the motive was more apparent. Riccobene had made the highly risky decision to return to the area from the Federal Witness Protection Program after testifying against a number of Mafia members. Anastasia needed to cover that murder as well, literally on the fly. By the time he was in the air toward Denver's Stapleton Airport he was dictating the story to an editor over a passenger telephone. "The people next to me on the plane start looking at me funny, because I'm dictating this mob story on the phone," he recalls. "I'm on a flight from Spokane to Denver, calling in a story about a mob shooting in South Jersey."

The combined opus of his reportage forms a kind of twisted morality play. "Basically what the Mafia does is take the traditions of an Italian-American family and bastardize them: honor, loyalty, and family," Anastasia explains. "This next generation of guys didn't even believe in the bastardized values. They just believed in 'Get it all, get it now, what's in it for me?' And when they got jammed up and found themselves facing potential prison sentences, they looked to cut a deal."

A prime example is Nicky Crow Caramandi. A con man of legendary skill, he lived a cash-and-carry existence. Free of any driver's license, holding no insurance, he peddled phony merchandise, ran betting pools and numbers rackets, anything to make a fast buck. He joined the Mafia and rose to the highest ranks of the Philadelphia family and, after plotting and carrying out a number of murders, eventually reported directly to Nicky Scarfo. But when police approached him, he simply took the easiest way out by squealing on his mob "family." Then he took the next logical money-making step. In 1986, he got word to Anastasia through an FBI agent that he wanted to do a book. The agent set up the meeting at the federal building in downtown Philadelphia and left the two alone in a room with a long table.

It was the reporter's first face-to- face meeting with an admitted gangster. Caramandi was dressed in a brown suit and tie, none of the flashy gold chains worn by some of his colleagues. He was friendly and had a firm handshake. In short, he was, well, charming. At first glance, Anastasia was impressed. But then, he says, "You gotta remember, these guys have killed people, they're cutthroats. They're not even immoral, they're amoral."

The result, after hundreds of hours of taped interviews, was Blood andHonor, a sometimes humorous but mostly chilling account of the downfall of Little Nicky Scarfo. The book, published in 1991, is complete with real-life back-alley shootings, extortion, fancy restaurants, and hoods in trenchcoats. Or, at least, as real-life as possible. "I can't verify a lot of this stuff," Anastasia admits. "If Caramandi tells me why something happened, the guy on the other side of that why is either dead or inaccessible."

Likewise, the drunken threat from Spike Gregorio was another sign of troubled times for the Mafia. "That kind of typified the state of the Scarfo crime family," Anastasia says, shaking his head. "A guy calls you collect to threaten you. I wouldn't get that from the older guys. They understood everybody's role. These younger kids don't seem to understand anybody's role, even their own."

ALL OF WHICH MAKES FOR sad tales but great reporting. Anastasia has no plans to leave the business anytime soon. He has become instead what an economist would call a horizontal corporation, diversifying while staying within the field. His first book sold more than 100,000 copies. He has appeared on Geraldo. He is getting feelers from movie producers. Respectful editors at the Inquirer give him free rein to chase down whatever story he wants. And he is working on a third book, a kind of real-life Marriedto the Mob. This book, like his first one, approached him through the FBI.

A few months ago, the ex-wife of Ronald "Cuddles" DiCaprio, a New Jersey mob associate now serving 20 years for racketeering, called Anastasia. She had discovered her husband's involvement in several underworld murders, and she was afraid that he would kill her too. So she went to the FBI. Her courtroom testimony against the six-foot-three, 250-pound Cuddles helped put him behind bars.

But there was an added bit of drama, she told Anastasia. "My story's about something your other two books didn't have," she said. "Mine is about sex." Mrs. Cuddles now had a new married name: Mrs. Woltemate. She had married the FBI agent assigned to guard her. Thanks to this plot twist, Married to the Mob gets combined with The Bodyguard.

A killer scenario, true to lite Who wouldn't stick to a beat like that?

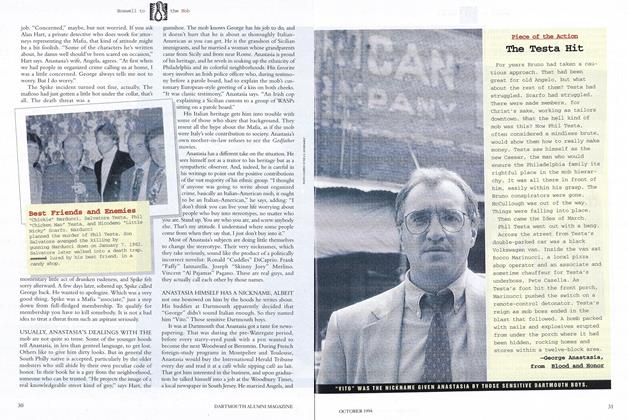

Best Friends and Enemies "Chickie" Narducci, Salvatore Testa, Phil "Chicken Man" Testa, and Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo. Narducci planned the murder of Phil Testa. Son Salvatore avenged the killing by gunning Narducci down on January 7, 1982. Salvatore later walked into a death trap, conned lured by his best friend, in a candy shop.

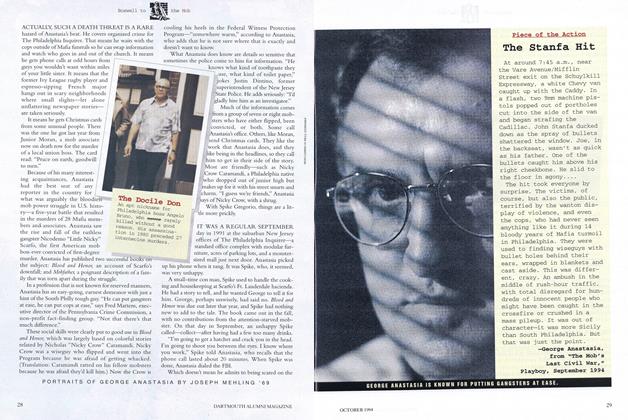

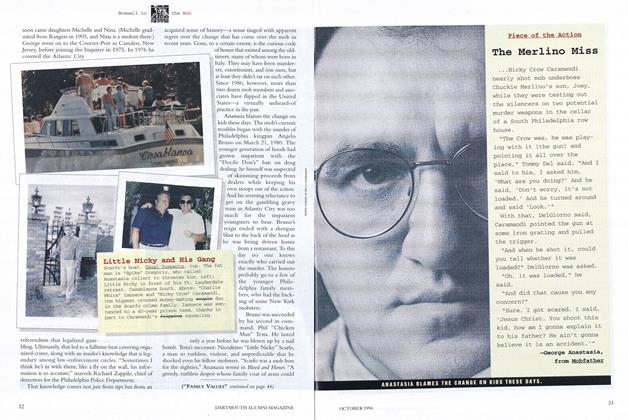

Little Nicky and His Gang Scarfo's boat, Usual Suspects, top. The fat man is "Spike" Gregorio, who called Anastasia collect to threaten him. Left: Little Nicky in front of his Ft. Lauderdale retreat, Casablanca South. Above: "Charlie White" lannece and "Nicky Crow" Caramandi, the biggest crooked money-making couple duo in the Scarfo crime family. lannece was sentenced to a 40-year prison term, thanks in part to Caramandi's flipping squealing.

Little Nicky and His Gang Scarfo's boat, Usual Suspects, top. The fat man is "Spike" Gregorio, who called Anastasia collect to threaten him. Left: Little Nicky in front of his Ft. Lauderdale retreat, Casablanca South. Above: "Charlie White" lannece and "Nicky Crow" Caramandi, the biggest crooked money-making couple duo in the Scarfo crime family. lannece was sentenced to a 40-year prison term, thanks in part to Caramandi's flipping squealing.

Little Nicky and His Gang Scarfo's boat, Usual Suspects, top. The fat man is "Spike" Gregorio, who called Anastasia collect to threaten him. Left: Little Nicky in front of his Ft. Lauderdale retreat, Casablanca South. Above: "Charlie White" lannece and "Nicky Crow" Caramandi, the biggest crooked money-making couple duo in the Scarfo crime family. lannece was sentenced to a 40-year prison term, thanks in part to Caramandi's flipping squealing.

The Docile Don An apt nickname for Philadelphia boss angelo Bruno, who rarely killed without a good reason. His assassination in 1980 preceded 27 internecine murders.

IT'S FOR YOU. Chicken Man and Little Nicky in the salad good days.

TOM AVRIL is a starry-eyed punk whohas written about hair implants, violentpets, and male strippers as a reporter out ofthe suburban New Jersey office of ThePhiladelphia Inquirer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

October 1994 By Varujan Boghosian -

Feature

FeatureBait & Bullet and the Politically Correct

October 1994 By Sydney Lea -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Testa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Merlino Miss

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

Tom Avril '89

Features

-

Feature

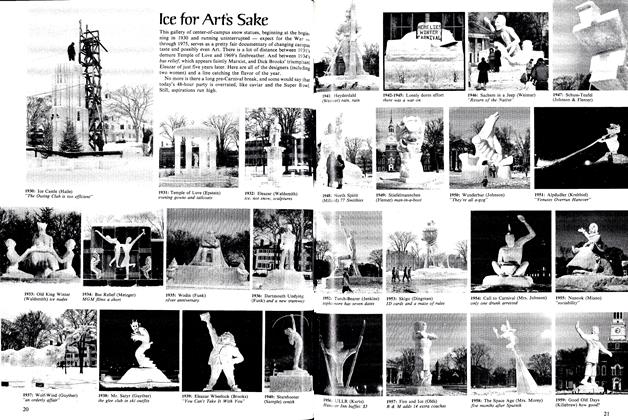

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMateo Romero '89

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureA BRIGHT FUTURE

July/Aug 2010 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

MARCH 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD ROMAN SPEAKS TO US STILL

June 1976 By DAVID SHRIBMAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham