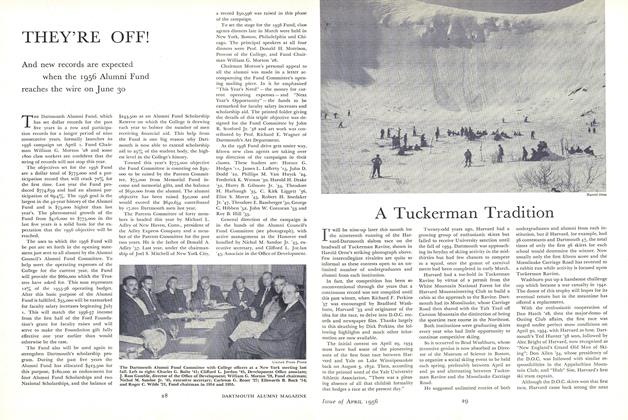

According to Jack Wennberg, what underlies many physicians'practices isn't so much hard science but shibboleths assumptions about the effectiveness of much medical treatment that aren't warranted by the facts. There is rarely a sinrest "right" answer in medicinejust "composites of probabilities and patient preferences," as Wennberg puts it "I"d guess that only ten percent of medicine is a wager against death. The rest is a quality of life, or patient preference, matter." By Susan Dentzer '77

Warning: the film you are about to see is for medically mature audiences only.

Several men in their 60s and 70s appear on a video screen, talking about a decision that more than 300,000 Amerimen make each year whether or undergo surgery to remove a portion of the prostate.

The first man, who decided to have the surgery, describes how it helped. "It was such a feeling of relief. I remember the day I walked into my urologist's office, singing, 'Summertime... and the peeing is easy.' On another occasion I described to him my ability now my regained ability to put my initials in the snow."

A second man, who elected toforgo surgery, describes how he feelsnow. "My symptoms go up and down like the stock market. There is the sense of needing to get to the toilet in a hurry because of discomfort. All the tickets on the airliner or in concerts or theater had better be on the aisle so I can get out in a hurry if I need to. I don't go through a three-hour movie without having to leave."

A third man, who also had surgery, talks about his problems afterwards including "retrograde ejaculation," a condition where semen retreatsinto the bladder during sex. "I was stunned. It was a climax and all of a sudden I had this sensation and nothing happened.. .And I had leakage [of urine], I think the word is incontinence. This was a minus, a big minus. I'm annoyed with myself I figured surgery was like having your hair cut or something. Surgery you just can't take lightly. It can be, depending on the person, very serious."

Fade to black.

Coming soon to a tharter near you? Well, to a doctor's office near you, maybe. This unorthodox piece of cinema verite is the work of an unlikely group of filmmakers led by Dr. John E. Wennberg, professor of epidemiology in the Department of Community and Family Medicine at Dartmouth Medical School. With a title like "Choosing: Prostatectomy or Watchful Waiting," Wennberg and his colleagues don't expect the film to captivate the critics in Cannes. It's simply one of the tools they hope will revolutionize American health care.

The film, actually an interactive videodisk, is the first of many that may ultimately be produced at Wennberg's growing "studio" in Hanover. There, since coming from Harvard Medical School to DMS in 1979, Wennberg has helped put Dartmouth at the forefront of what is now one of the hottest areas of health-care research. Known as the "outcomes" movement, this field has one basic premise: although America spends almost $700 billion a year on health care, physicians and patients have only a vague notion whether much of it does any real good. At worst, we could be wasting a third or more of all health-care expenditures on medicine of dubious value.

Wennberg wants to change that and as a result, he has proselytized coast to coast on the urgent need to explore the real outcomes of many medical and surgical procedures. He was instrumental in creating a new center for outcomes research at the medical school; moreover, his tireless lobbying also helped convince Congress to create a new federal agency pumping tens of millions of dollars a year into the field. Without better information on outcomes, and brakes to slow the health-care system's furious growth, Wennberg believes, physicians and hospitals will keep overtreating many patients. That would waste precious resources that should be used to ensure adequate access to health care to those who need it, including the estimated 33 million Americans who now lack health insurance.

Wennberg's fervor stems from three decades of exploring the mysteries of medicine. The 56-year-old physician, who grew up in Bellows Falls, Vermont, and in Washington state, is a graduate of Stanford and of McGill Medical School in Montreal. Trained in internal medicine, he also earned a master's degree in public health from Johns Hopkins, where he began his longstanding focus on epidemiology. Today he is part sociologist, economist, consultant, and healthservices expert: more likely to quote the philosopher Michel Foucault than Marcus Welby, and more at home with statistics than with a stethoscope. A health nut, he eats only low-fat food (his wife, Coralea, can whip up a mean turkey chili). He keeps a breakneck pace, yet friends say he has mellowed a bit from the hard-charging, proud academic he was in years past. Most comfortable in jeans, Wennberg now spends much of his time in a suit, logging thousands of miles each year as a nationally known health-care consultant.

But his central preoccupation remains epidemiology, the study of the patterns of disease and medicine's answer to detective work And that's why Wennberg reacted with the tenacity of Sherlock Holmes when he first came upon the case of the Doctors Who Performed Too Many Tonsillectomies.

VARIETY MAY BE THE SPICE OF LIFE but should it be the stuff of a science, like medicine? Wennberg began pondering that question in the early 19705, while serving as director of a Vermont state program trying to make certain that good medical care and adequate health facilities were available throughout the state. The only way to find that out was to do what epidemiologists often do: use computers to assemble large databases about incidences of disease and treatment, then conduct statistical analyses to determine who has been getting sick and where. Wennberg and his staff went from hospital to hospital and community to community in Vermont, collecting information about scores of medical procedures. In effect, they put the state's entire health-care system under the microscope. And what they saw was as amazing as any new germ that ever popped up on a scientist's slide.

In a word, they saw variations huge, inexplicable variations in the rates at which many different medical procedures were being performed from place to place. Take tonsillectomies: in Middlebury, a small town about an hour and a half northwest of Hanover, Wennberg and a colleague, Alan Gittlesohn, compiled statistics showing that seven percent of young people under the age of 16 received the routine childhood operation. But in Morrisville, about an hour and a half north of Hanover, 65 percent of children appeared to have the procedure. That was a dramatic difference that seemed to make no sense. How could children in one place be plagued with so many more sore throats, swollen tonsils, and infected adenoids as children in another? "We had a tiger by the tail," Wennberg recalls today.

It turned out that the town's tonsillectomies were being performed by five local physicians, a mix of family practitioners and surgeons. Unbeknownst to them, their practice patterns were as remote from the rest of Vermont's physicians as if they'd been on an island in the Pacific. They weren't yanking tonsils out of kids' mouths to torture them, or to fill up their own appointment books; they were doing it because they thought it was good medicine. When Wennberg and his colleagues showed them the variation data that clearly made them out to be outliers, the doctors were astounded, and after looking into the medical literature vowed to perform fewer surgeries. "One said he was glad that all this had happened, because there were so many gall bladders that needed tending to," Wennberg recalls.

The physicians weren't alone, for Wennberg and his researchers began to see dozens of other practitioners performing procedures at far higher rates than their colleagues. Soon they noticed other strange patterns: some procedures, like hernia operations or hospitalizations for heart attack or stroke, tended to be done at about the same rate from place to place while others, like hysterectomies or surgery for lower back pain, exhibited the same odd swings as tonsillectomies. For patients, it appeared, anatomy wasn't always destiny; often, geography was.

Wennberg and colleagues began to consider a variety of hypotheses to explain these "small area variations," as they called them. Were some doctors performing too many operations because they were greedy? Even George Bernard Shaw had suggested that a society where surgeons were paid to chop off legs was likely to be inhabited by lots of amputees. But while there may have been a few bad apples, Wennberg and company found that the vast majority of doctors performing high rates of surgery were like the doctors of Morrisville: they seemed honestly to believe that it was in patients' best interests. When confronted with evidence of the variations, moreover, doctors tended to go through a series of stages. At first, they were "madder than hell," in Wennberg's words, and questioned the validity of the data; next their doubt gradually gave way to belief; belief sparked arguments among doctors over why the variations occurred; and then physicians performing high rates of procedures quickly changed their ways. "I certainly was a classic example of this process," says Dr. Robert Keller '58, DMS '59, who first met Wennberg in 1982 and is now executive director of the Maine Medical Assessment Foundation, an organization formed with Wennberg's help to examine variations in medicine among the state's physicians.

Consumer demand didn't seem to account for the variations, either. Wennberg and his career-long colleague, Floyd Fowler, interviewed people around Vermont. Hard as they looked, they couldn't find evidence of patients begging physicians for procedures in one town while residents of other areas turned up their noses at them. Nor were the variations confined to Vermont: in every location the researchers eventually studied including Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, lowa, and even England and Norway large differences in treatment patterns appeared.

For lack of any better explanation, Wennberg and his fellow researchers finally began chalking up the differences to what they called "practice-style factor" the ways in which doctors chose to practice medicine that seemed based more on habits or hunches than on any real scientific assessments. Physicians were apparently developing these hunches to fill a gaping intellectual hole in medicine: many common medical and surgical procedures hadn't really been examined or studied in a scientifically valid way. A perverse double standard existed in health care; while the United States was spending about $2 billion a year on randomized clinical trials of new drugs, almost nothing was being spent to determine how much a heart bypass really helped a man with artherosclerosis, when a pregnant woman needed a caesarian section, or whether children who had received tonsillectomies would have fared better without them. In a sense, far from being the omnipotent paragons of science that the public believed they were, modernday physicians didn't seem all that far removed from ancient medicine men. And it was science's and society's fault for not giving them the right tools.

And so the discovery of small area variations and practicestyle factor helped spawn the field of medical outcomes research. Or, as it is described by Dr. John Wasson, a close associate of Wennberg's at the Medical School: "Outcomes, let's face it, that's just jargon. The important thing is the patient's ability to function, the quality of life. If I chop out a guy's prostate, how does he pee?" Dr. Arnold Relman, editor in chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, has dubbed the outcomes movement the Third Revolution in health care-the dawn of a new "era of accountability" in medicine, following earlier upheavals that drastically expanded the size of the health-care system and then struggled unsuccessfully to brake the skyrocketing costs. Although it remains uncertain whether outcomes research will ultimately save much money by eliminating unnecessary procedures, it clearly promises to improve the quality of care many Americans receive. "I am bullish that the 1990s will lead to significant improvements in the factual basis for scientific decision making," Wennberg told a gathering at the prestigious Institute of Medicine, an arm of the National Academy of Sciences, last fall. "I believe the 1990s will be as important for the evaluative clinical sciences as the 1950s and '60s were for the biomedical sciences."

The flowering of the outcomes research movement gives new impetus to Wennberg's own vision of reform. "The thing that makes Wennberg very special is that he is able to combine an analytic capacity with a very practical eye," says Richard S. Sharpe, program director of the John A. Hartford Foundation, which has awarded Wennberg and fellow researchers roughly $2 million over the years to carry out their work. "He's done as much as anybody I know in trying to change the national health agenda."

An essential element in that agenda, Wennberg believes, is what could be called Patient Empowerment-giving individuals the knowledge and information to make intelligent health-care decisions.

THE OUTCOMES MOVEMENT is in its infancy, but its growth is far enough along to have developed several branches. Some of its leading exponents, such as Dr. David Eddy of Duke University, think one fruit of outcomes research will be to rationalize health care through the development of "practice guidelines" for physicians. Large numbers of patient medical records could be analyzed to determine the effects over time of different types of medical and surgical treatment. The conclusions would then be synthesized into algorithms that would suggest to physicians the optimal treatment options for sick patients. In a somewhat simplified example, a "sore throat algorithm" might lead doctors though a sequence of steps of treating sorethroat victims encouraging them to prescribe aspirin first, then take a throat culture and then, depending on the patient's response, it could proceed up the ladder to more sophisticated treatments, instead of throwing costly lab tests and high-tech health care at a patient right off the bat.

While Wennberg approves of the effort to develop practice guidelines, he is skeptical that they alone will do the job of removing much of the uncertainty of medicine. The reason, simply, is his Uncertainty Principle, which holds that there is rarely any single "right" treatment in medicine. Faced with a multitude of consequences that could follow any given medical procedure, informed patients might have varying desires for treatment based on their understanding of the probable harms and benefits and their own attitudes toward risk. Allowing them to exercise greater choice in their own care calls for a shift away from our traditional "doctor's orders" model of medicine, where patients have expected doctors to tell them what is good for them and doctors have readily complied.

If patients were really informed about the risks and benefits of many medical procedures, Wennberg contends, they'd often make choices different from their doctors', and they might turn much of it down. Informing patients was the goal he and his colleagues sought when they decided to make the prostatectomy videodisk. In the early 1980s Wennberg and a team of medical researchers had begun working with a group of urologists in Maine to examine variations in prostatectomy a common surgical treatment for a condition known as benign prostatic hypertrophy, or BPH. The ailment results in older men when the prostate, for unknown reasons, expands and squeezes the urinary tract, potentially triggering episodes of "acute retention," or inability to urinate. BPH itself isn't fatal, although acute retention must be treated by a urologist, who uses a catheter to drain away the collected urine. Prostatectomy, or removal of a portion of the prostate, is often prescribed for patients who feel they can no longer live comfortably with the symptoms of BPH.

In some communities in Maine, more than half of the men appeared to get the operation by age 85, while in others only 15 percent did. Local urologists disagreed sharply about when and whether patients really needed surgery: some argued that prostatectomies were a useful preventive measure that kept BPH from progressing to potentially fatal conditions such as kidney and urinarytract disease. Other urologists contended that the disease seldom led to these problems, and believed most patients could reasonably forgo surgery if they felt they could tolerate the BPH symptoms.

To clear up the confusion, Wennberg organized a research team with representatives from a handful of major universities (including Dartmouth) to study the actual outcomes of undergoing a prostatectomy and of "watchful waiting" that is, forgoing surgery while closely monitoring BPH symptoms to see whether they worsened. They pulled data together from many sources, such as hospital bills submitted to the federal Medicare program. Harvard researchers on the team, led by Dr. Michael Barry, then built a sophisticated computer "decision tree" to simulate the results of choosing surgery or watchful waiting. The model was able to predict that for 70-year-old men with BPH, immediate surgery resulted in a loss of about a month of actual life expectancy, but an overall gain of nearly three "quality-adjusted" months of life when improvement in symptoms were factored in. In effect, the results disproved doctors' "prevention" argument, since overall life expectancy clearly decreased following the operation.

Meanwhile, Wennberg's colleague Floyd Fowler, who is now a social psychologist at Dartmouth, developed ways to examine the attitudes of BPH patients. The results showed a wide disparity in the way patients felt about the disease: some with severe symptoms reported little effect on their daily activities, while others with mild symptoms were bothered a great deal. Of those "watchful waiters" who elected to put off surgery, about ten percent would find their symptoms worsening over time, roughly 30 percent would get better, and about 50 percent would stay the same. Among those who elected surgery, 79 percent who initially had moderate symptoms now reported far fewer of them, but 15 percent remained the same and six percent said their symptoms had worsened. Finally, about 25 percent of prostatectomy patients experienced unpleasant side effects; within three months of surgery, 20 percent had a postsurgical infection, eight percent ended up back in the hospital, roughly five percent reported bouts of impotence (these appeared to have psychological, not physiological, roots), and about four percent were incontinent.

Given the range of risks and benefits, Wennberg and his colleagues concluded that only patients could legitimately decide whether to undergo surgery and shouldn't be talked into it by overly enthusiastic surgeons or out of it by overly skeptical internists. In 1987, the Hartford Foundation awarded them a grant to study these preferences among BPH patients. But how best to feed patients information so that they could really understand the choices? A research colleague of Wennberg's, Dr. Albert Mulley '70 of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, had seen interactive videodisk technology used at MGH to give patients a role in clinical decisions. And Apple Computer's new HyperCard software made it relatively easy to produce this marriage of computers and TV. About a year and a half and some $250,000 later, the prostate videodisk made its debut in several clinical trials around the nation.

The results suggest that, confronted with the potentially negative outcomes of surgery, patients may be more risk-averse than physicians. For example, of 284 BPH patients who viewed the movie at Kaiser Permanente, an HMO, in Denver, all but about 30 chose watchful waiting over surgery. And nearly all were enthusiastic about the videodisk. "People said, 'If I'd had all this before my gallbladder surgery I would've thought longer and harder about having it done,'" says Mary LaBrecque, an adult nurse practitioner and project coordinator for the videodisk clinical studies.

When patients get their hands on accurate outcomes information, Wennberg and his colleagues think, they may turn down much of the high-tech medicine that the healthcare system increasingly offers them. "My guess is that there's a lot more optimism about how procedures work than there's really a basis for," he says. But outcomes research and Patient Empowerment won't prevent unwise health-care investments. To eliminate unnecessary, inappropriate, and inordinately costly medicine, he says, the nation must do a better job of assessing the current distribution of doctors, beds, medical equipment and even health-care workers, through research such as that carried out by the Medical School's Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences. Then, where capacity is clearly excessive, carefully coordinated, broad-based steps could be taken to "reallocate" it; for example, by limiting the number of medical specialists in favor of more family-care physicians.

These views put him in the camp of those who favor more health-care regulation and planning an idea that went out of vogue during the 'Bos, when untrammeled competition reigned. But Wennberg has some innovative ideas for restructuring the system with carrots instead of sticks. In lowa, he is trying to persuade health-care payers and politicians to attempt some radical new surgery on high health costs. One possibility might be to limit the growth of medical prices but offer communities the chance to use their health-care dollars in creative ways such as by converting unneeded hospitals to nursing homes.

Wennberg's views have also had a major impact on sweeping health-system reforms underway in Oregon. Led by State Senate President John Kitzhaber '69, Oregon officials are attempting to guarantee access to health care for all the state's residents, while at the same time limiting universal health-insurance coverage to a basic package that will exclude much medicine of marginal benefit. Earlier provisions of the plan would have sharply restricted the health care available to the poor on Medicaid rolls, including many organ transplants along with much questionable care; by contrast, privately insured Oregonians would be left to get any care that physicians prescribed, needed or not.

Wennberg's colleague, Dr. Elliott Fisher, assistant professor of community and family medicine, pointed out the anomaly to Kitzhaber when he visited Hanover last year. "I thought about that, and said, 'You're right.' It opened my eyes," Kitzhaber says. As a result, Wennberg and Fisher are analyzing variations in hospital care and the overall capacity of Oregon's hospital system. Kitzhaber now hopes that by reining in excess capacity, the state will save so much money on health care that it can expand benefits for the poor.

Helping out on high-profile reforms of America's health-care system is a long way from counting tonsillectomies in rural Vermont. But in a powerful sense, Wennberg's work hasn't really changed in the three decades since he plunged into epidemiology "We're carving out islands of rationality in a sea of confusion," he says. And there are few places where that is more urgent than in how America cares for its health,

George BernardShaw suggestedthat a societywhere surgeonswere paid tochop off legswas likely tobe inhabitedby a lot ofamputees.

The outcomesmovement isthe ThirdRevolutionin healthcare, sayseditor ArnoldRelman of The New England Journal of Medicine.

Albert Mulley'70 had seeninteractivevideodisksused to helppatients makedecisions abouttheir owncare at MassGeneralHospital.

John Kitzhaber'69 hopes theresearch byWennberg andteam can helpOregon passalong healthcare savings tothe poor.

They put thestate's entirehealth-caresystem underthe microscope.And what theysaw was asamazing as anynew germ thatever popped up ona scientist's slide.

For patients,it appeared,anatomywasn't alwaysdestiny; often,geography was.

If patients werereally informedabout the risksand benefits ofmany medicalprocedures,Wennberg contends, they mightdisagree withtheir doctors'recommendationsand turn down many medicalprocedures.

Confrontedwith thepotentiallynegativeoutcomesof surgery,patients maybe morerisk-aversethan physicians.

Susan Dentzer '77 is a senior writer for U.S.News & World Report.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE BLUE ZOO

May 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

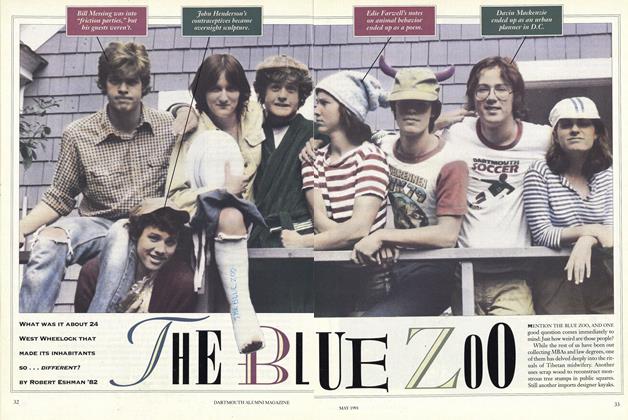

FeatureStory Time

May 1991 By Nancy Millichap Davies -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

May 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleTHEATERS OF WAR

May 1991 By Professor Lynda Boose -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1991 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1991 By W. Blake Winchell