An award-winning teacher reflects on reaching out to students.

One of the greatest fortunes of my career was to stumble, as an average-to-good student, into the office of an exceptional teacher. With his direction and encouragement and most of all, his confidence in my abilities I changed from a student dabbling in biology to an ardent scholar with clear career goals and aspirations. Throughout my years at the University of Washington, Professor Robert Fernald was fond of recalling the "day I stumbled" into his office.

People who are excited by their careers or who express genuine enthusiasm for a subject share a common denominator from their pasts: they all had an outstanding teacher. In my experience there are two essential elements to being a good teacher: enthusiasm for the field of study and taking a genuine interest in the personal and professional well-being of the students.

I also know from experience that good teachers are few and far between. Too many go through the motions without ever evoking emotions. For example, some professors routinely lecture over the heads of their students, perhaps to boost their own egos or to protect themselves from questions by intimidating the class. Such teachers may justify their style by asserting that it is the student's responsibility to do the reading necessary to understand what they are talking about. But in reality these teachers are abusing the purpose of a lecture. Lectures should make students want to explore the subject further by outside reading, not scare them into reading just to catch up. Intimidation has no place in teaching. I approach my class of 200 introductory biology students with the conviction that the best thing I can do for them is to use my own love of biology to stimulate them, make them ask questions rather than memorize answers, make them want to take more biology courses.

We professors should constantly think back to what courses made the greatest impact on our educations: quantitative, regurgitative courses filled with information or courses that stimulated us to consider novel ideas and broaden our horizons. It is not only the content of the course that is important, but the style. Like a dinner, it's not just the food but the presentation that counts. Asparagus overcooked is tasteless and limp; steamed the proper length of time it is quite another experience. If asparagus is on the menu for the day's lecture, it should be steamed properly. If professors rush through a bunch of facts that will be covered on the exam, they are missing the point and so are their students.

Not that content is unimportant. But in biology the conceptual bases are so beautifully packaged into elegant examples that it is a shame to present just the concept without the wrapping. So clothe natural selection in the diversity of butterflies, the seasonal camouflage of the snowshoe hare, the warning coloration of striped skunks. Wrap sexual selection in the dance of fireflies and coevolution in the interplay of insect herbivores and plant chemical defenses or in the combative, erratic flight of bats and moths. The natural world is both beautiful and brutal. Nothing in nature need be embellished the examples are far more thrilling than science fiction. Professors who cannot package an exciting lecture in these mantles are in the wrong profession.

Especially in beginning courses the wrapping is more important than the content assuming that the contents are sound. In biology the conceptual foundations are so interwoven that majors will be exposed to them again and again. A concept they encounter for the first time in the introductory course will be expanded upon, and expounded on, in upper-level courses. And we all know that redundancy is the key to commitment to memory. But in a beginning course, when students are exploring, wondering if they are interested in the subject, what is most important is how the material is delivered. In fact, all courses should be treated as if they were introductory courses-introductions to another level of understanding and appreciation, extensions beyond the horizons of previous courses. True, there is more content to cover, but it still can be packaged into delightful, digestible servings.

Beyond enthusiasm for the subject, the other ingredient necessary for good teaching is to have a genuine interest in the students. There is nothing more positively reinforcing for students than to feel that someone they respect cares about their opinions and aspirations. Often they don't even know that they need such reinforcement, let alone know where to find it. It is important for professors to be available. All too often in a large class it is the student who takes the initiative to see if the professor is a real person or a cardboard standup with a "Return in 15 minutes" sign taped to the office door. An initial impression that a professor is not available becomes the lasting impression.

Interest in students' personal and professional well-being cannot be faked. Teachers can develop it by increasing their interactions with students: dropping in on labs, getting to know students by their names and their interests. It's a self-perpetuating reward system: as professors' interest in their students increases, students will be more receptive, more attentive, more intrigued by what the profs have to say.

Sometimes it seems an impossible task. One day before an exam an introductory-level student asked me, "Do we need to know the scientific names of the animals you mention in class, like jan...jan...." "'Janthina?" I supplied. The student breathed in relief. Janthina is a beautiful snail with a paper-thin purple shell that floats around the Caribbean on bubbles it forms with mucus from its foot. I had used it as an example of how a bottom-dwelling organism evolved the ability to traverse open water to prey upon another former bottom-dweller. "What I really want you to remember is the theme of the story, to appreciate the beauty and plasticity of the selective process that would allow for the evolution of such an elegant lifestyle," I told the student, whereupon he proceeded to erase his lecture notes right before my eyes. Sure, he would get into medical school, but at the expense of his liberal arts education. Professors face this kind of student every day. Good profs do it without becoming jaded; exceptional professors change these students with their energy and enthusiasm.

At the end of my embryology course I compare the developmental fates of cells and selves to bring home to my students the concept of prospective potential and prospective fate. Their prospective fate is who they are and what they have accomplished when they reflect upon their lives at the end of their lives. Their prospective potential is the entire range of who they could have become and what they could have accomplished. Professors have the capacity to influence who our students become. We can broaden their prospective potentials while molding their prospective fates, all the while urging them to pursue the potential that brings them the most enjoyment in life. Therein is the greatest responsibility of teaching and the greatest reward.

Biology Professor Christopher Reed:"Nature is beautiful and brutal."

This month's "Syllabus" is a posthumous adaptation of an article that Associate Professor of Biology Christopher Reed published in the journal Bioscience to address fellow biologists on how to teach well. Reed had already racked up impressive credentials by the time he wrote his article: since arriving at Dartmouth in 1982 he had been awarded the Gross Taylor and Cornelia Pierce Williams Assistant Professorship of Biological Sciences and the J. Kenneth Huntington Memorial Award for outstanding undergraduate teaching. His wife, Paula Borden Reed, who assisted in the preparation of this article, recalls that Reed's mother suggested that he might want to wait until he was more senior before sharing his views on teaching. His response, says Paula Reed, was "Why wait?" This spirit of carpe diem infused Reed's approach to the science of life from the moment his University of Washington undergraduate studies evolved into his life's work. He pursued his doctoral research on invertebrate biology at Washington's Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories, then did a post-doc in marine biology at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Biology.. After coming to Dartmouth he spent summers researching bryozoans at Wood's Hole Marine Biological Laboratory. The research was one part of Reed's devotion to biology. The classroom was die other. The object of both: learning as much as possible. "He worked with students some nights until five in the morning," recalls his close friend and fellow Dartmouth Biology Professor Melvin Spiegel. In January of 1990, at age 38, Christopher Reed lost the fight. It was a fight he had lived well. He probably didn't know it, but his resolve in the face of adversity taught those of us on the sidelines an enduring lesson in the art of life. Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

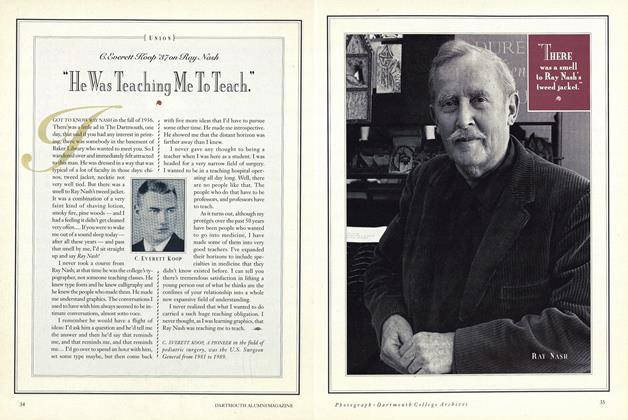

FeatureC. Everett Koop '37 on Ray Nash

November 1991 By Ray Nash -

Feature

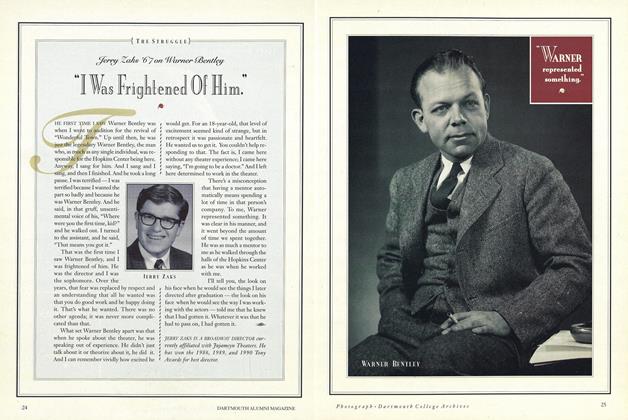

FeatureJerry Zaks '67 on Warner Bentley

November 1991 By Warner Bentley -

Feature

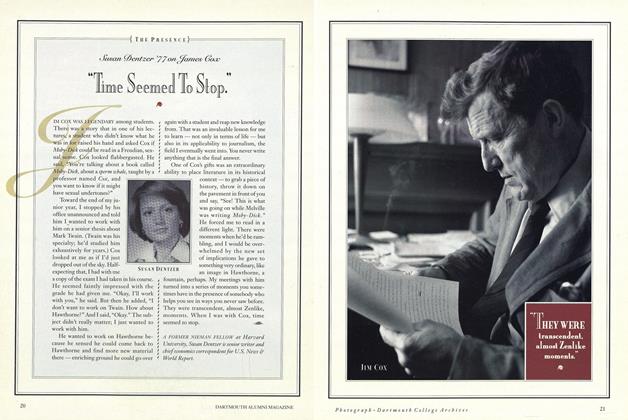

FeatureSusan Dentzer '77 on James Cox

November 1991 By Jim Cox -

Feature

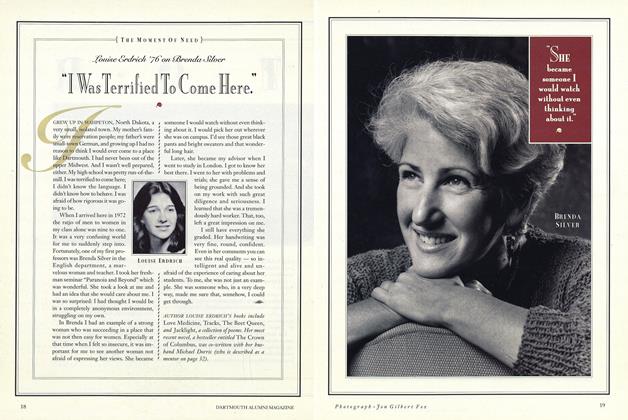

FeatureLouise Erdrich '76 on Brenda Silver

November 1991 By Brenda Silver -

Feature

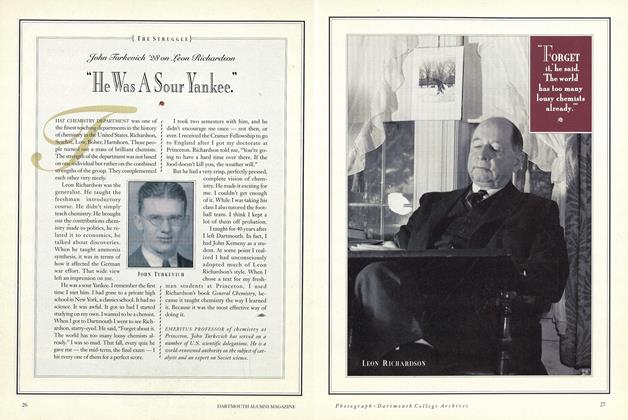

FeatureJohn Turkevich '28 on Leon Richardson

November 1991 By Leon Richardson -

Feature

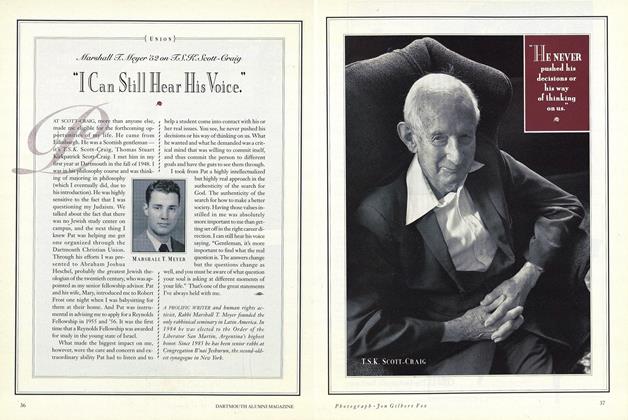

FeatureMarshall T. Meyer '52 on T.S.K. Scott-Craig

November 1991 By T.S.K. Scott-Craig