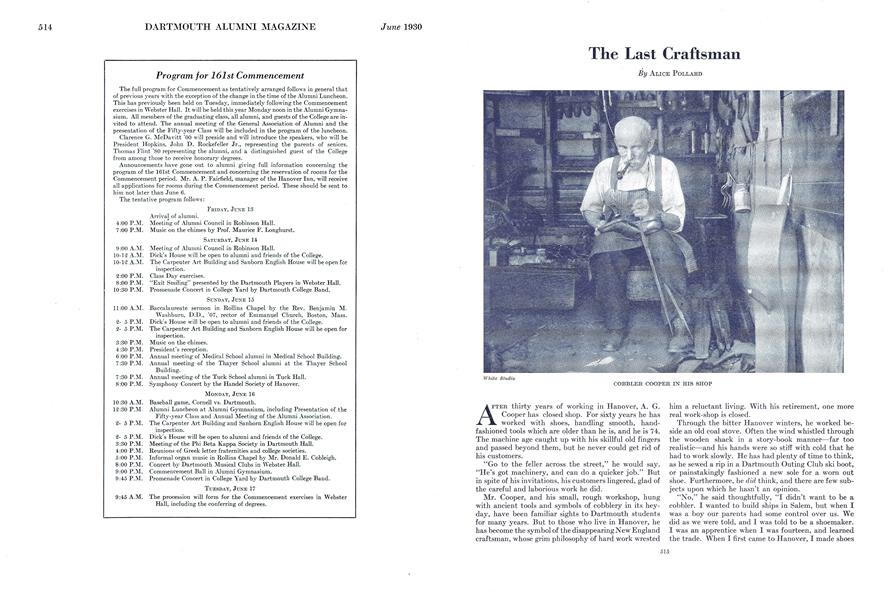

AFTER thirty years of working in Hanover, A. G. Cooper has closed shop. For sixty years he has worked with shoes, handling smooth, handfashioned tools which are older than he is, and he is 74. The machine age caught up with his skillful old fingers and passed beyond them, but he never could get rid of his customers.

"Go to the feller across the street," he would say. "He's got machinery, and can do a quicker job." But in spite of his invitations, his customers lingered, glad of the careful and laborious work he did.

Mr. Cooper, and his small, rough workshop, hung with ancient tools and symbols of cobblery in its heyday, have been familiar sights to Dartmouth students for many years. But to those who live in Hanover, he has become the symbol of the disappearing New England craftsman, whose grim philosophy of hard work wrested

him a reluctant living. With his retirement, one more real work-shop is closed.

Through the bitter Hanover winters, he worked beside an old coal stove. Often the wind whistled through the wooden shack in a story-book manner—far too realistic—and his hands were so stiff with cold that he had to work slowly. He has had plenty of time to think, as he sewed a rip in a Dartmouth Outing Club ski boot, or painstakingly fashioned a new sole for a worn out shoe. Furthermore, he did think, and there are few subjects upon which he hasn't an opinion.

"No," he said thoughtfully, "I didn't want to be a cobbler. I wanted to build ships in Salem, but when I was a boy our parents had some control over us. We did as we were told, and I was told to be a shoemaker. I was an apprentice when I was fourteen, and learned the trade. When I first came to Hanover, I made shoes as well as mended them. But of course that's all past. No one wants a hand-made pair of shoes nowadays."

Mr. Cooper believes that the rate of living today is harder on the individual than the plain hard work of the past.

"Work never killed a person," he maintained with a chuckle. "If it did, me and my wife would both be dead. It's fast living what takes it out of you. Life moves too fast for me today. I saw the building up of this country -—the growing of the cities and the cutting of the forests. That was the time to live. Now everyone is busy using up what was started. No one wants good work. They don't care if things don't last. They are in such a hurry. They would rather have three pair of shoes in one year, than one pair of shoes that would last three years."

Mr. Cooper believes that the women today have it remarkably easy. "My wife had thirteen children to care for. She made their clothes, and did all her own housework. She was busy all day until late at night. Of course, the kids learned to help early. They were trained to work when they were young. But they had a good time, too. They used to slide and play outdoors, and were all in bed by five each night, before I got home. They were up at five in the morning."

When asked how his wife liked to work so hard, Mr. Cooper looked surprised. "I never asked her and she never said. She just did it."

The old cobbler came to Hanover when it was a small oasis in the wilderness, a tiny village between the hills. The snows were heavier than they are now.

"It seemed as though there was a giant on the top of the hills, sending the snow down by shovelfuls," he said. "We don't have the snows we used to, because the timber has been cut. That's what holds the snow."

He remembers Dartmouth College when it was a very small school indeed, and Hanover itself covered no more acreage than a small farm.

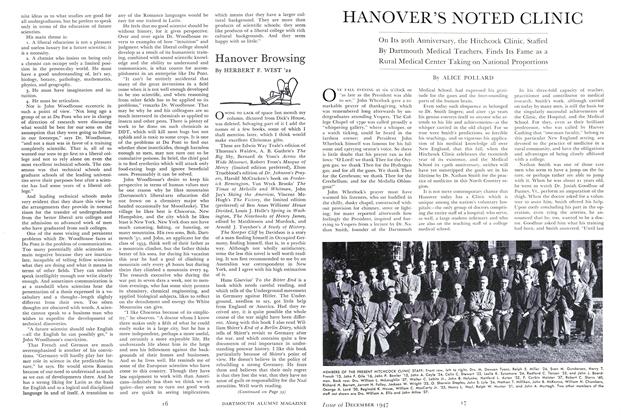

COBBLER COOPER IN HIS SHOP

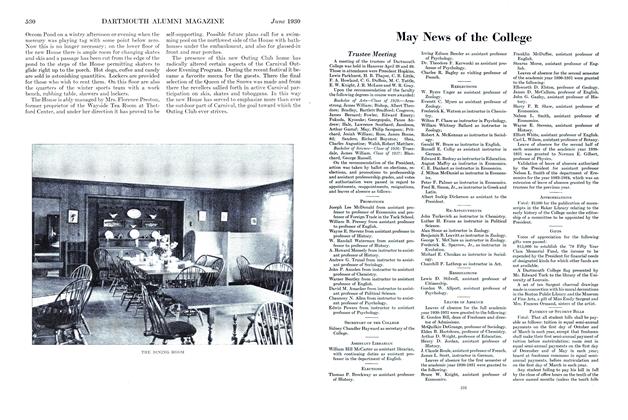

PROF. JOHN MERRILL POOR Department of Astronomy

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

June 1930 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleThe Use of Leisure

June 1930 By Nelson A. Rockefeller -

Article

ArticleA Student on His Own

June 1930 By H. S. Embree -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

June 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1930

Alice Pollard

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S RIVER

June 1945 By Alice Pollard -

Article

Article"THE LOOSE-ENDERS"

January 1946 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

ArticleHANOVER'S NOTED CLINIC

December 1947 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

ArticleSheepskin Season Recalls a Mystery

June 1953 By Alice Pollard -

Article

ArticleNow It's Reunion Week

July 1955 By ALICE POLLARD