In the beginning, Hebrew was standard college fare.

When Hebrew was added to the Dartmouth course offerings in 1987, few, if any, students and faculty realized that it was making a comeback rather than a debut. As the then recendy appointed assistant professor of Hebrew, I, too, wasn't aware that Hebrew at Dartmouth had a history reaching back to the earliest days of the institution. Then Philip Cronenwett, head of Baker Library's special collections, showed me a small, brittle manuscript from the commencement file of the College archives. Written in a fine Hebrew hand and dated July 16, 1799, it was a Dartmouth commencement address, delivered by one Jacob Patch. This was the dawning of my realization that the study of the Hebrew Bible in its original tongue was an important part of the intellectual landscape of colonial New England.

Hebrew came to New England on the Mayflower. Pilgrims William Bradford and William Brewster were heirs to a tradition of Christian Hebraism that accompanied belief in the divine authority of the Bible. Idealizing Hebrew and the Bible, the Puritans saw themselves as analogous to the Hebrews and saw America as the new Israel. These ideas persisted through the Revolution—the British were the Egyptians, King George III was pharoah—until the United States became more secularized in the early 1800s. Reflecting Puritan values, Dartmouth, Harvard, Yale, and other schools of higher education founded before the Revolution focused on the study of theological treatises, rhetoric, and the learned languages—Greek, Latin, and often Hebrew and Aramaic. But always this was a Christian undertaking; there were few Jews in the colonies and fewer still in higher education.

Eleazar Wheelock was a product of this educational tradition. After studying Hebrew at Yale, he included the language in the curriculum of Moor's Indian Charity School. One of his most proficient Hebrew and Aramaic students was none other than Samson Occom. So intrigued was Occom with the Hebrew texts describing "the last days" that he worked out an American interpretation of the prophecies of Daniel Chapter Eight—a chapter which has provoked centuries of eschatological speculation. In 1767, on the back of his Hebrew grammar book, Occom jotted down "Some new thoughts as to Prophetic Numbers," predicting that the Second Coming would occur between 1847 and 1849. Occom's scriptural citations, along with the numerical calculations by which he arrived at that date, cover three closely written pages, now preserved in the Dartmouth Library Special Collections.

When Eleazar Wheelock founded Dartmouth, he gave Hebrew a special place of prominence. This was evident in the structure of the curriculum, the appointment of faculty, and the acquisition of Hebraica for the College library. The College seal was designed with the the Hebrew phrase "El Shaddai" (one of the forms of the divine name) at its apex. In 1777 Wheelock engaged John Smith, Dartmouth class of 1773, as "Professor of English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldee, etc.... to teach which, and as many of these and other such languages as he shall understand, and also to read lectures on them, as often as the president, tutors, etc., with himself shall judge profitably for the seminary." During Smith's tenure, seven of the College's commencement speeches were given in Hebrew; no doubt these orations, as well as those delivered in Latin and Greek, were composed under his supervision. Dartmouth's Hebraist also wrote A Hebrew Grammar, one of the earliest texts on Hebrew published in the United States.

Whereas at Harvard and Yale the stern professors who tried to impose the study of the Hebrew language on their students met with resistance and minimal success, Smith's progam at Dartmouth fared better—and lasted longer. He kept Hebrew studies alive for 36 years, until he died in 1809. Although a professor of Greek and Latin was appointed in 1811, the Hebrew professorship was left unfilled. A Mr. Horowitz, an itinerant Jewish teacher, was employed on a part-time basis to teach Hebrew and French, a notable exception to the then standard American practice of depending upon Protestant ministers for Bible and Hebrew instuction.

In 1825 Benjamin Hale, a professor at the Medical School taught Hebrew for two seasons. "Not, perhaps," he said, "much to the profit of my classes but because I happen to be fresher in the study than any college officer." Hale's double-duty presaged a shift in the previously inflexible curriculum of the College, which, along with the curricula of other New England colleges, had been called "as rigid and inexorable as fate." Reflecting the increasing secularization of society, emphasis now shifted to the natural sciences and the literature and languages that formed the core of the humanist tradition.

Although Hebrew was no longer taught at Dartmouth after Hale's time, the Bible in translation was. During the nineteenth century the greatest proponent of Bible study at Dartmouth was President Samuel Colcord Bardett, class of 183 6, formerly a professor of Bible at the Chicago Theological Seminary. He journeyed to the Middle East to study Hebrew and the Bible in their original setting, and upon his return wrote FromEgypt to Palestine. Carrying the tradition of Biblical studies into the twentieth century, Professors Roy Chamberlain and Herman Feldman edited TheDartmouth Bible in the 1940s and published several editions of it between 1950 and 1960.

These contributions to the study of the Bible at Dartmouth still fell short of realizing John Smith's long-dormant wish "to facilitate the study of the scriptures in the original." When the College reintroduced Hebrew in 1987 as part of the Asian Studies Program—and fittingly housed it in Bartlett Hall—the emphasis was on modern Israeli Hebrew. A year later a course in reading Biblical texts reappeared on campus. Most recently, Hebrew studies have been enhanced at the College with the establishment of the Brownstone Visiting Professorship in Hebrew and Judaic studies. No doubt Professor Smith would be pleased.

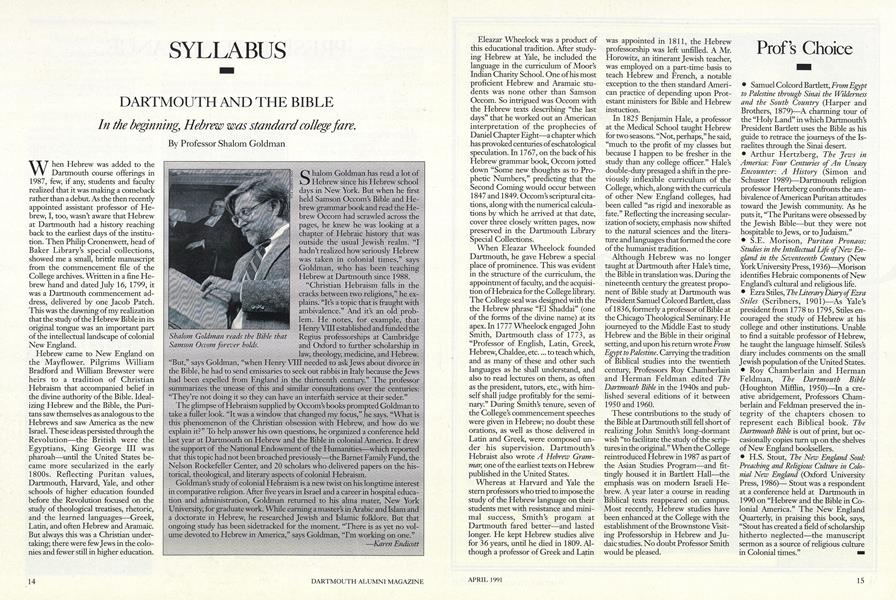

Shalom Goldman has read a lot of Hebrew since his Hebrew school days in New York. But when he first held Samson Occom's Bible and Hebrew grammar book and read the Hebrew Occom had scrawled across the pages, he knew he was looking at a chapter of Hebraic history that was outside the usual Jewish realm. "I hadn't realized how seriously Hebrew was taken in colonial times," says Goldman, who has been teaching Hebrew at Dartmouth since 1988.

"Christian Hebraism falls in the cracks between two religions," he explains. "Its a topic that is fraught with ambivalence." And it's an old problem. He notes, for example, that Henry VIII established and funded die Regius professorships at Cambridge and Oxford to further scholarship in law, theology, medicine, and Hebrew.

"But," says Goldman, "when Henry VIII needed to ask Jews about divorce in the Bible, he had to send emissaries to seek out rabbis in Italy because the Jews had been expelled from England in the thirteenth century." The professor summarizes the unease of this and similar consultations over the centuries: "They're not doing it so they can have an interfeith service at their seder."

The glimpse of Hebraism supplied by Oceom's books prompted Goldman to take a fuller look. "It was a window that changed my focus," he says. "What is this phenomenon of the Christian obsession with Hebrew, and how do we explain it?" To help answer his own questions, he organized a conference held last year at Dartmouth on Hebrew and the Bible in colonial America. It drew the support of the National Endowment of the Humanities—which reported that this topic had not been broached previously—the Barnet Family Fund, the Nelson Rockefeller Center, and 20 scholars who delivered papers on the historical, theological, and literary aspects of colonial Hebraism.

Goldman's study of colonial Hebraism is a new twist on his longtime interest in comparative religion. After five years in Israel and a career in hospital educa- tion and administration, Goldman returned to his alma mater, New York University, for graduate work. While earning a master's in Arabic and Islam and a doctorate in Hebrew, he researched Jewish and Islamic folklore. But that ongoing study has been sidetracked for the moment. "There is as yet no volume devoted to Hebrew in America," says Goldman, "I'm working on one."

Karen Endicott

Shalom. Goldman reads the Bible thatSamson Occom forever holds.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

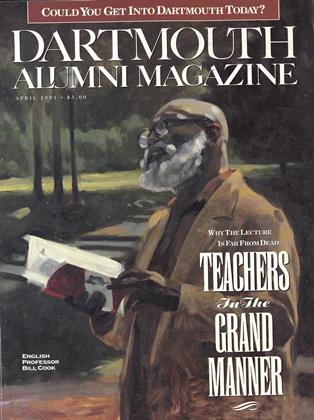

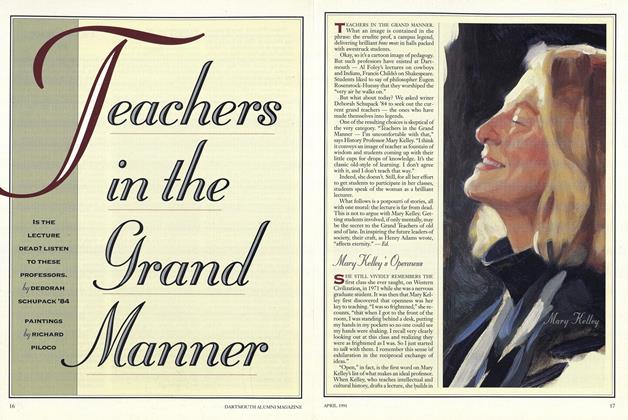

Cover StoryTeachers in the Grand Manner

April 1991 By DEBORAH SCHUPACK '84 -

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

April 1991 -

Feature

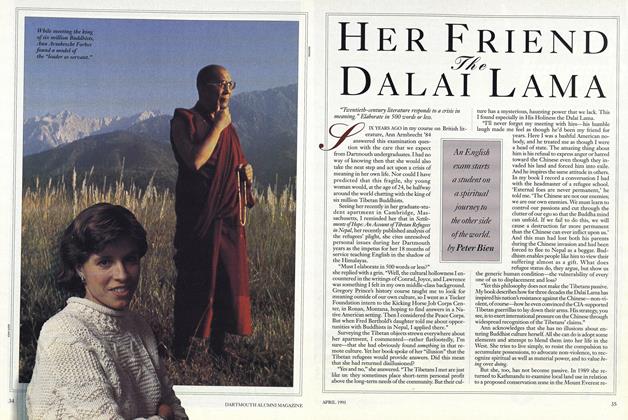

FeatureHer Friend the Dalai Lama

April 1991 By Peter Bien -

Feature

FeatureSTEVE KELLEY IN TWO ACTS

April 1991 By ROBERT ESHMAN '82 -

Feature

FeatureCOULD I GET IN TODAY?

April 1991 -

Feature

FeatureDisengagement

April 1991 By John Sloan Dickey '29