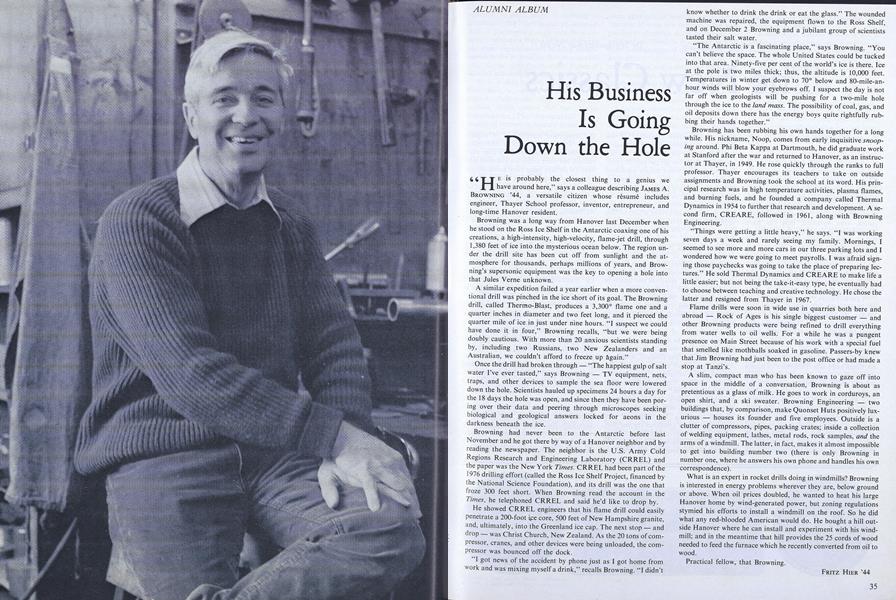

"He is probably the closest thing to a genius we have around here," says a colleague describing JAMES A. BROWNING '44, a versatile citizen whose resume includes engineer, Thayer School professor, inventor, entrepreneur, and long-time Hanover resident.

Browning was a long way from Hanover last December when he stood on the Ross Ice Shelf in the Antarctic coaxing one of his creations, a high-intensity, high-velocity, flame-jet drill, through 1,380 feet of ice into the mysterious ocean below. The region under the drill site has been cut off from sunlight and the atmosphere for thousands, perhaps millions of years, and Browning's supersonic equipment was the key to opening a hole into that Jules Verne unknown.

A similar expedition failed a year earlier when a more conventional drill was pinched in the ice short of its goal. The Browning drill, called Thermo-Blast, produces a 3,300° flame one and a quarter inches in diameter and two feet long, and it pierced the quarter mile of ice in just under nine hours. "I suspect we could have done it in four," Browning recalls, "but we were being doubly cautious. With more than 20 anxious scientists standing by, including two Russians, two New Zealanders and an Australian, we couldn't afford to freeze up again."

Once the drill had broken through — "The happiest gulp of salt water I've ever tasted," says Browning — TV equipment, nets, traps, and other devices to sample the sea floor were lowered down the hole. Scientists hauled up specimens 24 hours a day for the 18 days the hole was open, and since then they have been poring over their data and peering through microscopes seeking biological and geological answers locked for aeons in the darkness beneath the ice.

Browning had never been to the Antarctic before last November and he got there by way of a Hanover neighbor and by reading the newspaper. The neighbor is the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) and the paper was the New York Times. CRREL had been part of the 1976 drilling effort (called the Ross Ice Shelf Project, financed by the National Science Foundation), and its drill was the one that froze 300 feet short. When Browning read the account in the Times, he telephoned CRREL and said he'd like to drop by.

He showed CRREL engineers that his flame drill could easily penetrate a 200-foot ice core, 500 feet of New Hampshire granite, and, ultimately, into the Greenland ice cap. The next stop - and drop — was Christ Church, New Zealand. As the 20 tons of compressor, cranes, and other devices were being unloaded, the compressor was bounced off the dock.

"I got news of the accident by phone just as I got home from work and was mixing myself a drink," recalls Browning. "I didn't know whether to drink the drink or eat the glass." The wounded machine was repaired, the equipment flown to the Ross Shelf, and on December 2 Browning and a jubilant group of scientists tasted their salt water.

"The Antarctic is a fascinating place," says Browning. "You can't believe the space. The whole United States could be tucked into that area. Ninety-five per cent of the world's ice is there. Ice at the pole is two miles thick; thus, the altitude is 10,000 feet. Temperatures in winter get down to 70° below and 80-mile-an-hour winds will blow your eyebrows off. I suspect the day is not far off when geologists will be pushing for a two-mile hole through the ice to the land mass. The possibility of coal, gas, and oil deposits down there has the energy boys quite rightfully rubbing their hands together."

Browning has been rubbing his own hands together for a long while. His nickname, Noop, comes from early inquisitive snooping around. Phi Beta Kappa at Dartmouth, he did graduate work at Stanford after the war and returned to Hanover, as an instructor at Thayer, in 1949. He rose quickly through the ranks to full professor. Thayer encourages its teachers to take on outside assignments and Browning took the school at its word. His principal research was in high temperature activities, plasma flames, and burning fuels, and he founded a company called Thermal Dynamics in 1954 to further that research and development. A second firm, CREARE, followed in 1961, along with Browning Engineering.

"Things were getting a little heavy," he says. "I was working seven days a week and rarely seeing my family. Mornings, I seemed to see more and more cars in our three parking lots and I wondered how we were going to meet payrolls. I was afraid signing those paychecks was going to take the place of preparing lectures." He sold Thermal Dynamics and CREARE to make life a little easier; but not being the take-it-easy type, he eventually had to choose between teaching and creative technology. He chose the latter and resigned from Thayer in 1967.

Flame drills were soon in wide use in quarries both here and abroad - Rock of Ages is his single biggest customer — and other Browning products were being refined to drill everything from water wells to oil wells. For a while he was a pungent presence on Main Street because of his work with a special fuel that smelled like mothballs soaked in gasoline. Passers-by knew that Jim Browning had just been to the post office or had made a stop at Tanzi's.

A slim, compact man who has been known to gaze off into space in the middle of a conversation, Browning Is about as pretentious as a glass of milk. He goes to work in corduroys, an open shirt, and a ski sweater. Browning Engineering — two buildings that, by comparison, make Quonset Huts positively luxurious — houses its founder and five employees. Outside is a clutter of compressors, pipes, packing crates; inside a collection of welding equipment, lathes, metal rods, rock samples, and the arms of a windmill. The latter, in fact, makes it almost impossible to get into building number two (there is only Browning in number one, where he answers his own phone and handles his own correspondence).

What is an expert in rocket drills doing in windmills? Browning is interested in energy problems wherever they are, below ground or above. When oil prices doubled, he wanted to heat his large Hanover home by wind-generated power, but zoning regulations stymied his efforts to install a windmill on the roof. So he did what any red-blooded American would do. He bought a hill outside Hanover where he can install and experiment with his windmill; and in the meantime that hill provides the 25 cords of wood needed to feed the furnace which he recently converted from oil to wood.

Practical fellow, that Browning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

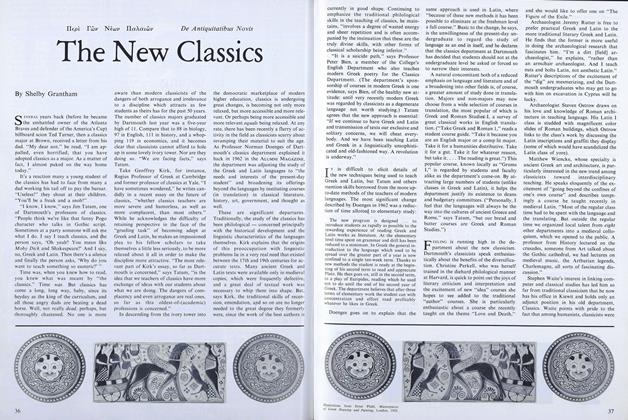

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

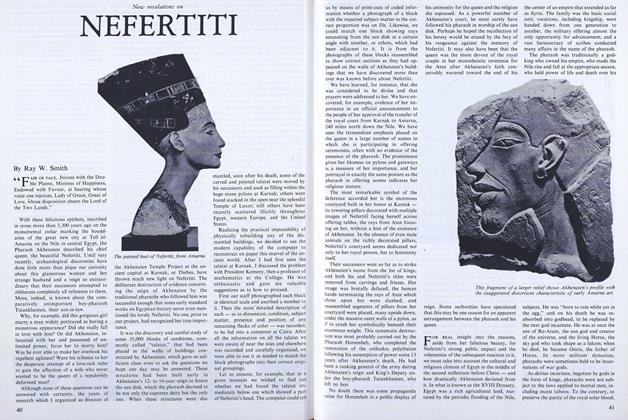

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R.

FRITZ HIER '44

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Full Disabled Life

October 1995 -

Books

BooksTHE CATCH AND THE FEAST.

JANUARY 1970 By FRITZ HIER '44 -

Feature

FeatureDingwall of Dartmouth

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleSo Much More Than a Reunion

June 1994 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleSabbaticals for the Rest of Us

April 1995 By Fritz Hier '44