Hollywood pictures America's ambivalence about Vietnam.

It took me six months in Vietnam to wake up and turn all the World War II movies off in my mind," Vietnam veteran Thomas Bird wrote in The New York Times last year. Like countless other Americans, Bird had grown up with Hollywood's unambivalently heroic image of American participation in World War II. Even his desire to go fight in Vietnam was, he admits, largely a by-product of heroized movie images.

The sentimentalized heroics of World War II films were the result of pressure brought to bear on Hollywood by the Office of War Information, created in 1942 to promote and sustain a pro-war climate in America. After the war, the O.W.I. loosened its hold on civilian films, but Hollywood, threatened by McCarthyism, continued to promote pro-military films throughout the Korean War.

Hollywood's representations of World War II and Korea served America's war effort more extensively than even the O W.I. could have imagined. Long after the real wars ended, their reel versions kept right on playing, reinscribing a powerfully influential genre that valorizes war by transforming its brutality into tests of manly endurance, heroism, and patriotism. The American war film belongs to the national myth of victorious conquest, and, like its cousin the Western, is scripted by the racially constructed narrative of self vs. other, Cowboy vs. Indian, white American vs. "gook."

Then came Vietnam, when myth fell short of observable reality. And it was Thomas Bird's generation that began trying to revise the war myth by producing war films that attempt to oppose what they simultaneously represent—films like "Apocalypse Now," "Platoon," "Casualties of War," and "Born on the Fourth of July."

The most obvious exception was John Wayne's "The Green Berets." Wayne, recognizing the impact of the motion picture medium, wanted to make a World War 11-style film that would, as he wrote to President Johnson, convince the whole world "why it is necessary for us to be there." "The Green Berets" was the only major combat film made between the 1963 Diem coup and the 1973 withdrawal of American troops; it was also the only pro-war Vietnam film to be made until the 1980s and the only one assisted by the Department of Defense.

Otherwise, for the ten years that the war and the national controversy about it raged, Hollywood avoided Vietnam films. It was only obliquely that America "talked about" Vietnam on film through displaced allegory in films like "Little Big Man" or through stories like "Taxi Driver" that featured veterans who return to wreak the violence learned in Vietnam upon the American society that sent them there. In all such "violent vet" films, Vietnam stalks the edges like a hostile sniper, making illusory the very idea that peace could exist for the veteran or the society to which he returns.

It was not until 1978, three years after the fall of Saigon, that Hollywood was willing to explore the Vietnam War. The year 1978 saw the release of "The Boys in Company C," "Go Tell the Spartans," "Coming Home," "The Deer Hunter," "Who'll Stop the Rain" and "Hair." A sure sign of Hollywood's embrace, "The Deer Hunter" and "Coming Home" swept the Oscars.

Then in the 1980s President Reagan began an official move on the symbolic level to return the Vietnam War to the fold of unambiguous American heroics. The Reagan recuperation inspired a cycle of patriotic, pro-war films built around the illusion that there are still MIAs soldiers "Missing in Action" imprisoned in Vietnam. This fantasy like that of the violent veteran, a unique product of the Vietnam War seems less a consequence of realistic hope than of an unassuagable sense that America left something behind at the end of the war. In MIA films like the Rambo series, "Uncommon Valor," and "Missing in Action," that "something missing" is embodied as a group of emaciated and emasculated American men who must be rescued by American supermen. Buried within this fantasy is, moreover, a powerful suggestion that the problematic Vietnam legacy here reduced to the issue of "winning" can be resolved only through re-enactment.

In the Vietnam films of the 1980s, body image becomes the visual signifier of ideology. The techno-muscularity and behemoth invulnerability of Sylvester Stallone, Chuck Norris, and Arnold Swartzenegger reinscribe war as the supreme act of masculinity. Films that depict Vietnam as dehumanizing and morally insupportable feature, by contrast, the vulnerable, smaller, and often wounded bodies of Christopher Walken, Martin Sheen, Charlie Sheen, Tom Cruise, William Dafoe, and Michael J. Fox.

Despite their ideological polarization, all these narratives share certain features and certain gaps. What gets highlighted is loss, anger, and bewilderment. Yet even the films that are most critical of the war are oddly apolitical, leaving the representations of war strangely detached from real history. In film the anger against the government that fueled the actual Vietnam era has been defused from the political to the personal thus relocating blame, explicitly or implicitly, onto either the soldiers who enacted or the citizens who opposed U.S. policy rather than on the government that instigated it.

On January 16,1991, as the Gulf war unfolded, Hollywood studios suspended release of several new Vietnam films. As the first era of American films that depicted opposition to war abruptly ended, the Vietnam story remained incompletely told. The war had never been filmed from any perspective but that of the white male soldier, despite the disproportionate numbers of women and racial minorities who served. Nor had films explored the Vietnamese perspective. America's national psyche in Hollywood's view, at least seemed not yet ready, even after 18 years, to see the conflict through any anguish but, selectively, its own.

Vietnam, undermined, our war myths,says English Professor Lynda Boose.

Lynda Boose, then a young navy wife, arrived in Saigon days before the 1963 Diem coup. She spent the early years of the war at Subic Bay Naval Base in the Philippines shipping home the remains and personal effects of navy war casualties. As the war escalated, so did the shipments and the letters she wrote to the families of the dead and missing, many of whom she knew. "Every day I inventoried the remnants of a life. Each time I felt the sense of massive loss, the waste of all those lives," she recalls. "In the early days of the conflict, I didn't have a political perspective about the war-just pain." That changed after she returned to Washington in 1966 to work for New Mexico Senator Joseph Montoya and dealt with hardship discharges and the desperate letters Montoya got from mothers. "I came to feel strongly that we should never have been in the war," she says. "But, I couldn't stand being around the protests, because I had been too close to the war effort. The losses, the effort, and my pain became sacred. It took me two more years to get past that and become political." In 1968 Boose changed direction, returning to the University of New Mexico to finish her B.A. in English. A Woodrow Wilson fellowship took her to Stratford-upon-Avon to study Shakespeare, and she earned a Ph.D. in Shakespearean drama at UCLA. "I didn't read about the war during this time," she says, "I was trying to crawl away from it." But in 1989 she taught a course at Dartmouth on post-war representations of Vietnam. During it she had her students ask their parents about their views of Vietnam. "One parent wrote to me to thank me and say that it had been cathartic finally to talk about it. Another called me a 'feminist commie.' For the Vietnam generation the war clearly remains an impassioned issue," she says. Last fall Boose co-taught "American Culture and the Vietnam War" with history professor Douglas Haynes. In addition to classroom lectures, the exploration of the Vietnam War included a term-long film series, a Hood Museum exhibition of Dick Durrance's '65 war photos, and a bus trip to the the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C. "Perhaps it's best that Vietnam remain in the national consciousness as a troubled sign of American policy" reflected Boose after the course, "lest the nation glorify war or forget the moral anguish it leaves behind." Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

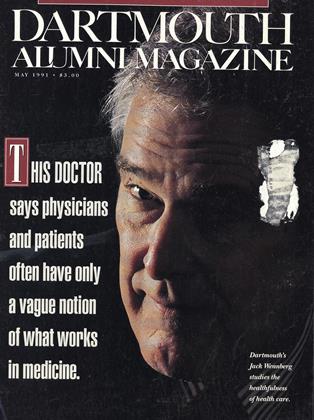

Cover StoryDOCTOR WENNBERG'S UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

May 1991 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

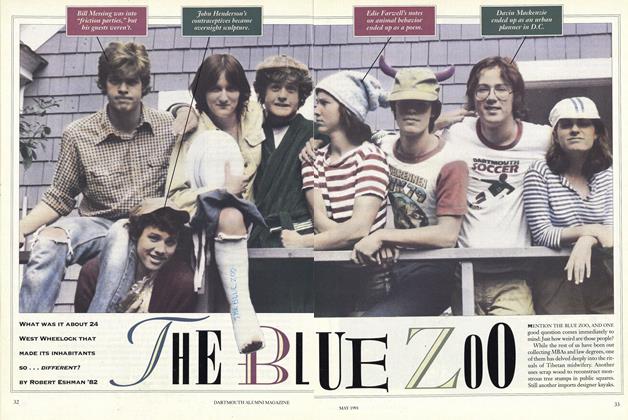

FeatureTHE BLUE ZOO

May 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

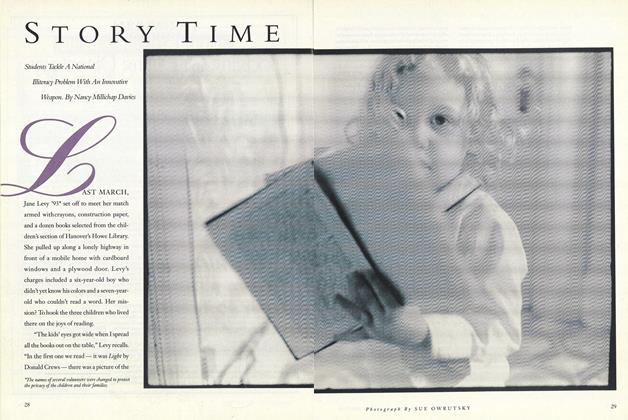

FeatureStory Time

May 1991 By Nancy Millichap Davies -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

May 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1991 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

Article

-

Article

ArticleCONCERNING THE RELATION OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL TO CERTAIN ALUMNI PROJECTS

-

Article

ArticleMusic Festival Begins April 29

April 1960 -

Article

ArticleSigns of "Women's Lib"

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleFor Leverone Field House, A New Look: Astro Turf

JULY 1972 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

MAY 1983 -

Article

ArticleBasketball

April 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45