Students Tackle A National Illiteracy Problem With An Innovative

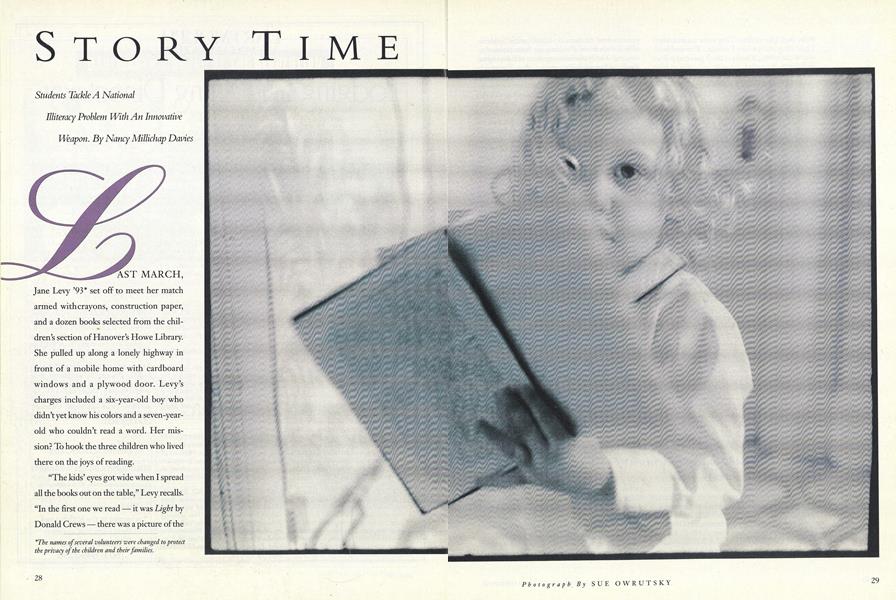

Jane Levy '93* set off to meet her match armed with crayons, construction paper, and a dozen books selected from the children's section of Hanover's Howe Library. She pulled up along a lonely highway in front of a mobile home with cardboard windows and a plywood door. Levy's charges included a six-year-old boy who didn't yet know his colors and a seven-yearold who couldn't read a word. Her mission? To hook the three children who lived there on the joys of reading.

"The kids' eyes got wide when I spread all the books out on the table," Levy recalls. "In the first one we read it was Light by Donald Crews there was a picture of the New York City skyline. They were amazed when I told them that's where I'm from. The next book was about a farm, which got them going on stories to tell me. After that, I'd make sure that at least some of the books I brought were about things they'd be familiar with snow, animals, fishing."

Levy is a Book Buddy, one of a hundred student volunteers in a nationally acclaimed Tucker Foundation program that battles illiteracy. In New Hampshire and Vermont, as in the nation generally, one in five adults is functionally illiterate, according to the U.S. Department of Education. That translates into 23 million Americans incapable of filling out a job application or ordering from a restaurant menu. Statistics for young adults are even more dismal: studies by the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that, among those aged 21 to 25, 73 percent can't interpret a newspaper story and 63 percent can't follow written map directions.

In the spring of 1989, those involved with the literacy project of the Tucker Foundation's Dartmouth Community Services were all too familiar with such grim numbers. They had opened a literacy outreach center in Orford, New Hampshire, but during the one term it operated it failed to attract learners. "What was really a short test period for a northern New England small town was a very long time for young college students to wait," says Jan Tarjan '74, associate dean of the Tucker Foundation, who has been developing Dartmouth's adult-literacy programs since 1984. She adds: "We dropped the project." Students who wanted to be involved clearly needed a different approach, one that would let them see results.

It was Tarjan who came up with the Book Buddies idea and gave the program its name. In a brainstorming session with literacy-project members, she proposed an effort in which Dartmouth students would read to children at risk of illiteracy. Her rationale came in part from a 1985 U.S. Department of Education study, A Nation at Risk, which had found that preschool children whose parents read to them do significantly better in school than those who have not been exposed to reading. The National Assessment of Educational Progress has similarly reported that illiteracy is an inherited disease: those with functionally illiterate parents are twice as likely as their peers to be functionally illiterate themselves. Starting with the children in their own homes might be a way to break the cycle, Tarjan thought.

Sue Shons '89, who chaired the literacy project at that time, took the idea to heart. She even stayed in Hanover after graduation, serving as volunteer coordinator for Dartmouth Community Services, in large part to get the Book Buddies program established. "The program would have had a very slow start if it were not for Sue Shons's energy and attention," says Tarjan. "She communicates a wonderful enthusiasm to students, teachers, and parents alike."

Plans for the project took shape that summer. Students who volunteered as Book Buddies would be matched for a term with children ranging from kindergarten age to second grade level with reading trouble. Once a week each Buddy would read to and with the child, as well as any other children who were in the home. The older children were to read with younger ones, giving the parents a model to work with and the entire family the impetus to share time reading together.

Teachers in Lebanon schools referred to Shons 30 children in the fall of '89, a total of 50 by that winter. Meanwhile, posters around campus attracted students in droves; when the program began operating, there were more volunteers than children. The spirited response was no surprise to Shons. "The first thing many students say when they walk through my door is, 'I want to work with children,'" she says. "And most Dartmouth students can't imagine the concept of not being read to."

The program has steadily increased in size. About 100 students were involved in the winter of 1991 a tenth of the total who volunteer for Tucker Foundation programs. Eleven sources now refer children, including area schools and such agencies as Head Start and the Haven, a shelter for the homeless in White River Junction, Vermont. Wherever the Buddies go, carpooling in their own vehicles or in the Tucker Foundation's four heavily booked cars, the goal is the same: to kindle excitement about books in children at risk.

A secondary goal, which die volunteers don't express direcdy, is to provide parents with a model of good reading habits, and to provide a "referral bridge," letting families who need more help know of adult-literacy programs. "Ultimately, we'd like to get parents reading to the kids themselves, getting them excited about stories," says Sue Shons. One resulting frustration: it's difficult if not impossible to tell whether it achieves results.

The students, though, seem to have little doubt about the program's effectiveness. "At the first home I was matched to," recalls Jane Levy, "toward the end of the term the seven-year-old actually read a page aloud, and the mother who'd been enthusiastic but not at all involved with what I was doing on any of my earlier visits sat in with us and read to the children. I'd been going there for only nine weeks, and there we were. For at least that hour, reading was in the home." Sam Bogardus '92* saw enthusiasm but not much change in his child's reading during the first term of their match. During their second term together, though, things began to click. "At first he'd look at a picture and try to guess what it said, but now when he gets really excited about a particular book, he'll want to read part of it. He tries to sound out the words, and he can struggle through. He's really improved since last summer."

Parents as well as Buddies have noticed the difference. Maureen Young, whose daughters have received a year's worth of visits from Diana Cadeddu '91, observes, "The girls look forward to Diana coming every week. She does more to personalize reading than the school can do asks them what they like and what they want to read more of. Sometimes they'll bring books home from the school library to share with her. And they've discovered that there are books Diana read as a child that they also enjoy, books they might not have come across otherwise." Cadeddu, who is one of the project's co-chairs, says this kind of comment is not unusual. "When I call the parents at the end of the term to find out how things went, 90 percent are really enthusiastic about the program," she says. "One mother whose child had a Buddy while the parents' marriage was breaking apart told me about the sense of stability that it gave her son to have his Book Buddy show up every week. They'd go out back and sit on a rock and read." The other ten percent, she admits, are upset because the Buddy never came or didn't come regularly. Preparticipation interviews for which students must keep an appointment now serve as a test of com- mitment: a student who doesn't show up won't be matched with a child.

Experts also seem to think the program works. The Student Coalition for Action in Literacy Education (SCALE) has begun publicizing it as an example for organizations around the country. SCALE, a national network of college and university students, administrators, and faculty committed to increasing literacy, includes a description of the Book Buddies program as one of five or six models on the flyer it distributes to its 400 active literary groups nationwide and to other campuses interested in developing programs. Reports Lisa Madry, SCALE's co-director, "When people talk to us about wanting to work with children or families, we use Book Buddies as a model and reference. 'Call Dartmouth,' we say."

What they don't say is that the volunteers may be among the biggest beneficiaries. Pete Anderson '93* recalls his first visit to a non-reading fiveyear-old this way: "At first I couldn't tell if he was interested, but while I was reading he kept moving closer, and eventually he put his head on my shoulder. When I left, he came running after me and gave me a big hug. I had a feeling right from that first day that I'd really made a connection."

Jane Levy discovered a benefit of her own: "Volunteering as a Book Buddy is a way of staying in touch with reality. Being up here at Dartmouth is like living in Fantasyland. Every visit I made to those three kids kept me from taking my Dartmouth experience for granted." m

Sue Shons'89 (withpen) leads aBook Buddiesmeeting.She stayedin Hanoverafter shegraduatedin large partto get theprogramstarted.

Jilliteracy is an inherited disease: those withfunctionally illiterate parents are twice as likely astheir peers to be functionally illiterate themselves.

*The names of several volunteers were changed to protectthe privacy of the children and their families.

Nancy Millichap Davies is manager of humanitiescomputing at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDOCTOR WENNBERG'S UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

May 1991 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

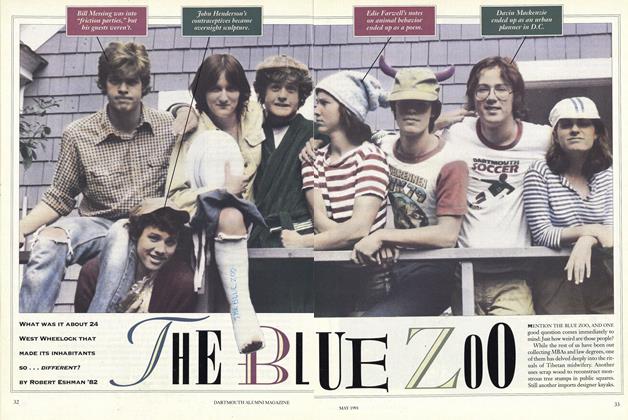

FeatureTHE BLUE ZOO

May 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

May 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleTHEATERS OF WAR

May 1991 By Professor Lynda Boose -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1991 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

Features

-

Feature

FeatureGuy P. Wallick '21 to Head Alumni Council for 1957-58

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

JUNE 1970 -

Feature

FeatureReady to Roll

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By RICK BEYER ’78 -

Feature

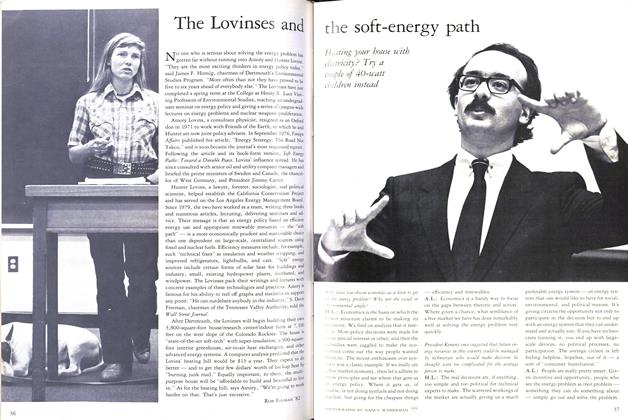

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

JUNE 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z.