Columbus sails on in the modern mind.

Columbus discovered America": few printable English sentences have more power. At its sound, pulses quicken, hackles rise, ink gushes. "Columbus did not discover America," say the sons of Knute; "Leif,Ericson did." "Columbus did not discover America," revisionist historians insist; "countless native inhabitants knew the place long before he stumbled upon it". "Columbus did not discover America," literalists argue; "he died thinking his four voyages had all taken him to Asia."

The dispute, it seems, has to do with history: did Columbus discover America in 1492, or did he not? The statement itself, however, is unhistorical in several respects. To begin with, "Columbus" was not the name of the man in question. So far as anyone knows, the captain of the Santa Maria was born Christoforo Columbo in Genoa, was called Christavao Colom during his stay in Lisbon, became Cristobal Colomo when he removed to Spain, took the name Cristobal Colon in order to claim kinship with the Roman General Colonius onius and a French admiral nicknamed Coullon, and refers to himself in surviving documents, variously, as Xpoual Colon, El Almirante, and "Xpo FERENS." In contemporaneous Latin writings he is Columbo, Colonus, and Colom, but never "Columbus." Nowhere is there any evidence that he was ever so-called, by himself or anyone else, or that he ever heard the name.

Nor did he ever hear the word "America," which was coined a year after his death, by Martin Waldseemiiller, to name the"new world" hypothesized in the letters of Amerigo Vespucci. As for the verb "discovered," that would have meant nothing to a man who knew no English. But even if he had known the language as it was spoken in his day, "discovered" would not have meant to him what it does to us. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest recorded use of "discover" to mean "obtain sight or knowledge (of something previously unknown) for the first time" occurs in 1555—in an English translation, as it happens, of Pietro Martire's account of the life and voyages of one "Christophorus Colonus (otherwise called Columbus)."

Trebly unhistorical, the statement is also ahistorical in its tendency to veil those differences between the past and the present upon which the idea of history depends. Because the word "America" unavoidably calls to our minds the geographical, politi- cal, and social entities we know by that name, Columbus seems to have "discovered" the America we inhab- it. Americans celebrate or revile Col- umbus, it has been said, because he discovered us. Standing there on the eastern shore of today's America, he seems to be our contemporary as well as our immediate forebear, a proto-modern American whose motives and actions account for the situa- tion in which we find ourselves.

In one respect, however, the proposition is truly historical: while the words themselves have been in constant use since the middle of the sixteenth century, their meanings have changed during that time. Waldseemiiller's "America" and ours are nominally identical but different in virtually every other respect—size, shape, population, global significance. The "Columbus" that Richard Eden introduced to English readers in 1553 was "a Gentleman of Italie" who "founde certayne Ilandes," not the jumpedup weaver's son who divided the world into Old and New, history into Ancient and Modern. The "discovery" announced by Eden in 1555 was a single, completed unveiling of something long hidden by God, not the beginning of a process that would last for 300 years. "Columbus discovered America" may not be history, but it certainly has a history.

Indeed, the statement embodies the very idea of history as perceived differences between the past and the present that can be considered changes because they occur in some temporally enduring entity. If we saw no differences between the past and the present, there would be no "past," and history would be unnecessary. If we saw no fundamental identity between past and present, there would be nothing to change, and history would be impossible, except as a chronology of unconnected differences. The different meanings attached to the words "Columbus discovered America" at different times separate the past from the present, demanding history. The identity of the words themselves over time connects past to present in a history of semantic change. And, insofar as those words are part of the language from which we construct our world, their history is ours.

Anyone who looks into the history of these three words will notice something remarkable: the semantic changes they have undergone during the last five centuries appear to have resulted primarily from their use in combination. A common English verb since the fourteenth century, "discover" originally meant "remove a cover from, display"; while the meaning "come upon" or "find" had been conveyed, since the later 1400s, by the word "invent." Once attached to the noun "America," however, the verb took over the meaning of "invent" and expanded semantically along with its object, acquiring an unwonted epistemological sense as "America" came, in the later sixteenth century, to denote a fourth part of the world, equivalent to Europe, Asia, and Africa, rather than a group of islands lying somewhere off the Asian coast of terra firma. And, as it became increasingly apparent that "America" had not been completely "found" by those who first saw it that, in the words of Thomas Heriot, the little known about this place "is nothing to that which remaineth to be discovered" the verb acquired the additional sense of "explore," effectually transforming the Columbus who "discovered America" from a finder of something already supposed to exist and now uncovered, into the originator of something previously non-existent and still coming into being as a result of explorations pursuant to his.

The history of these English words, in short, is American. "Columbus" arose to name an authority for the "discovery." "America" was coined to name the place "Columbus discovered." And "discovered" took on new meanings to account for the unprecedented experiences riences of people like "Columbus" in "America." The simplest of sentences, "Columbus discovered America" illustrates the sort of lexical, grammatic, and semantic changes undergone by the English language since 1500 as a direct result of its continual efforts to accommodate an ever-expanding "America" and to make sense of the endlessly changing new world that was born with the "discovery." Modern English is what it is largely because "America" entered the language in the sixteenth century and because the language invaded America in the seventeenth. Since then, the presence of "America" in English and that of English in America have grown apace, producing the "Americanized" English that is now spoken and written by Anglophones throughout the world.

Ralph Waldo Emerson must have been thinking along these lines when he called "Columbus" one of the "mind's ministers." He certainly was not talking about Spain's emissary to Las Indias. Like everyone else, then and now, Emerson knew very little about that supposed person. Nor could that person, whoever he was, have ministered to any nineteenth-century mind, since he died, in 1506, completely unaware of the existence, let alone the size and importance, of the world that would inhabit, and be inhabited by, such a mind. Emerson seems to have been talking, rather, about the word "Columbus" and its automatic predication "discovered America." In that sense, "Columbus" certainly is a minister of the modern mind: a symbol of the American origins and evolution of the language out of which the modern mind and the world it contemplates are made.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

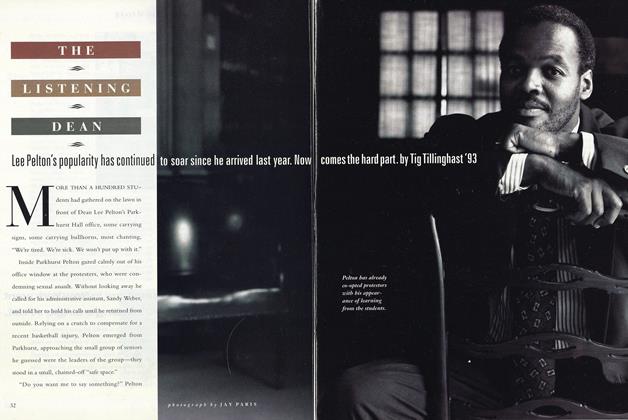

FeatureTHE LISTENING DEAN

October 1992 -

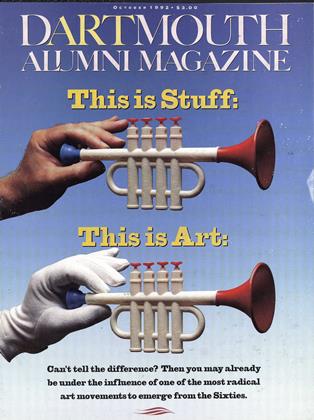

Cover Story

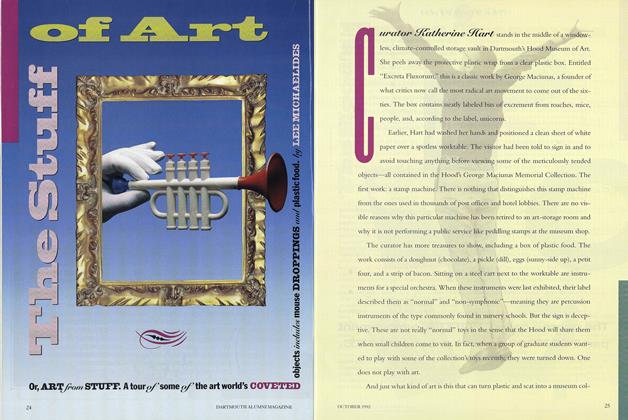

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Underground Curriculum

October 1992 By Tim Brookes -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1992 By Rick Joyce

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

JUNE, 1928 -

Article

ArticleGlass Memorial Funds

October 1946 -

Article

ArticleGifts and Bequests Total $1,785,501

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleWith Big Green Teams

April 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

NOVEMBER 1965 By HARRY SAVAGE M'27 -

Article

ArticleRembert Explains

September | October 2013 By Lauren Vespoli ’13