Lee Pelton's popularity has continued to soar since he arrived last year. Now comes the hard part, by Tig Tillinghast'93

MORE THAN A HUNDRED STUDENTS had gathered on the lawn in front of Dean Lee Pelton's Parkhurst Hall office, some carrying signs, some carrying bullhorns, most chanting, "We're tired. We're sick. We won't put up with it."

Inside Parkhurst Pelton gazed calmly out of his office window at the protesters, who were condemning sexual assault. Without looking away he called for his administrative assistant, Sandy Weber, and told her to hold his calls until he returned from outside. Relying on a crutch to compensate for a recent basketball injury, Pelton emerged from Parkhurst, approaching the small group of seniors he guessed were the leaders of the group—they stood in a small, chained-off "safe space."

"Do you want me to say something?" Pelton asked in a characteristically soothing, gentle tone.

"I don't know. Maybe it's better if you're just here to take this all in," said a '92 woman, gesturing to the group of students with signs and banners behind her.

"O.K. Do you want to talk?" Pelton asked. "Should I come in?" he added, looking at the chain divider.

"If you think it's an important thing for you to do," the woman said. "Do you want to?"

"Yeah," Pelton said.

A few minutes later, sitting crosslegged in a circle, students introduced themselves. From his seat beneath the tree outside his office, Dartmouth's highestranking student dean said "Hi, I'm Lee."

DARTMOUTH'S NEW DEAN OF Students Lee Pelton replaced Dean of the College Edward Shanahan last September, diving into a tumultuous first year. Showing an uncanny ability to listen at the right times and speak only at the right times, Pelton has brought to Dartmouth something the campus hasn't seen in decades—a wellliked dean. At least so far. At the cusp of his first unpopular decision—about fraternities, unsurprisingly—the question is how long the honeymoon can last.

Dean Shanahan knew a thing or two about unpopular decisions. He imple- mented a suite of them just before he left to preside over Choate Rosemary Hall in Connecticut. Shanahan did his successor a considerable political favor—something akin to a sacrifice fly in baseball. The announcements on fraternities, alcohol, and the disciplinary system, all decried by students, allowed Pelton room to maneuver when he came. He could make a few corrections that students could interpret as a deanly detente. Pelton arrived at a time when fraternities were beginning to buckle under a delayed-rush system, students lacked confidence in the disciplinary system, and kegs were no more.

His demeanor didn't hurt either. Dartmouth's new dean speaks with a slow cadence despite being one of the busiest people on campus. While interviewing him, this writer was easily able to type word-for-word everything he said into a portable computer—portable because Dean Pelton likes to interview outside. In fact, he likes to do most everything outside, including pedaling his bicycle to meetings. More often than not, he will ask his scheduled appointments, "Hey, it's a beautitul day. Want to do this on the Green?"

A tall, bearded man who most of the time looks as though he is carefully mulling over something somebody just told him, Pelton maintains what is perhaps the most hectic schedule at Dartmouth. In a recent interview, assistant Sandy Weber came out of Parkhurst (because he was on the Green, of course) and rushed over to Pelton's bench. "The Provost Steering Committee meeting was moved up to 8 o'clock," she said. "They put the new time on the agenda but I didn't read the agenda when they gave it to me. John and Mary are making a presentation now."

Pelton glanced up at the Baker Tower. The clock's hands were just moving past 8:15. "I have got to go," he said, already standing.

From his pocket, he pulled a one-bysix-inch slip of paper with his daily schedule laser-printed onto it. (Weber prepares this palm-sized where-am-I-now schedule for him every morning.)

"Come by at 2:30. 0.K.? See ya." He was already halfway across North Main Street.

The pocket schedule is vital. As dean of students, Pelton oversees the largest administrative unit at Dartmouth. He is in charge of most elements of student life: athletics, residential life, student activities, campus security, health services, the Academic Skills Center, class deans' offices, career services, and dining services, as well as the Skiway, Hanover Country Club, and Morton Farm. He also retains vice-presidential status and participates in developing long-term College policy.

"Today's a good day because I get lunch," he once told a reporter for The Dartmouth. "That usually happens only about twice a week."

OVER THE DECADES cleaning has become a much more complex and demanding job as colleges become more complex and demanding institutions. Where once deans were professional trouble-shooters, today they add many new responsibilities—such as formulating new policies to deal with complicated issues like race relations and sexual assault. They must also have the foresight to predict next term's great issues and begin to formulate responses.

Fred Jewett, who just completed his eighth year as dean of the college at Harvard, told this magazine, "There's no question the dean's role in general has expanded. Some issues have simply become more complicated—like the disciplinary issue where universities have come under scrutiny for not being in accordance with outside legal procedures. And sometimes it's just a matter that new or different issues become relevant to the campus—like race relations. All this takes a toll." When asked if that toll included a diminishing of a dean's academic role, Jewett responded with a sharp, "Yes, without a doubt." He added that, as new concerns drew deans' attentions, the luxury of dealing with students' academic lives gradually receded. "It's simply a matter of available time."

A NORMAL DAY FOR PELTON BEGINS at 7:30 or 8 a.m. and does not end until 8 or 9 p.m. "I go from meeting to meeting and usually don't have time to deal with all the paperwork that comes across my desk until the weekend," he said. "At Colgate, it was not quite at this pace. Dartmouth has been unrelenting." Extracurricular events, including numerous alumni social en-gagements, often consume much of his time outside the office, he said. "There are times when I go two or three days without seeing my daughter—and that's not from traveling, that's being here."

But Pelton's long hours and amiability have gone a long way to patch up past damage done to the studentadministration relationship. After nearly nine years at Dartmouth, Shanahan lost the trust of students, many of whom targeted him—fairly or unfairly—as personally responsible for all ills. A public forum in Webster Hall on the alcohol policy two spring terms ago became a public session for Shanahan-bashing. Students accused the man of being manipulative and loathe to accept student input.

Pelton seemed well aware of this atmosphere, and he came in with the obvious intent of changing it. He began his tenure in Hanover calling himself a freshman, sporting a Dartmouth '95 sweatshirt and walking around campus with his wife, Kristen Wilson, and their three-year-old daughter Jordan. In early October Pelton twice attached himself to particular students and followed them around all day long, attending classes and spending nights in Beta Theta Pi fraternity and in the Gold Coast dorms. He went to weight training with the football team, attended a Green Key meeting, and sat in on an undergraduate-advisors' meeting.

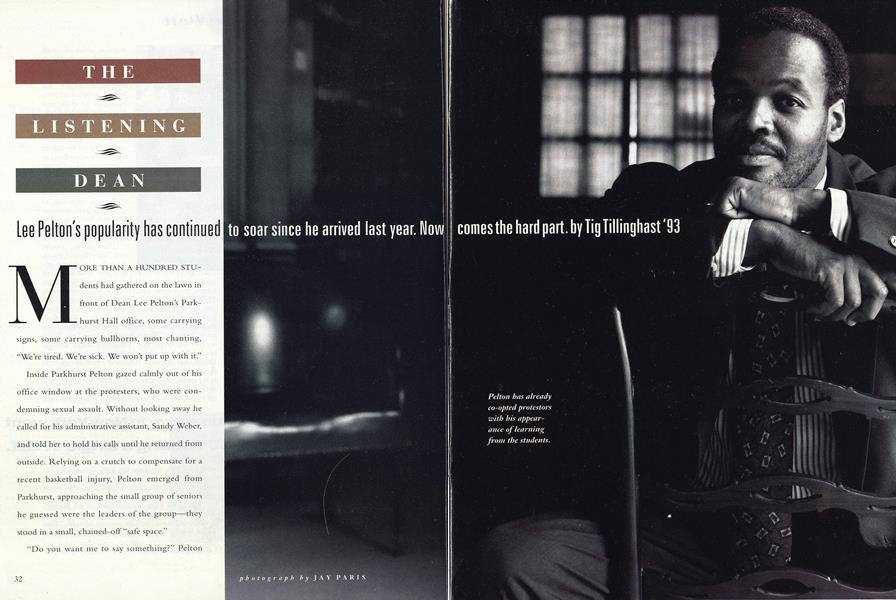

His appearance of listening and learning can co-opt even the most anti-administration protester. Take the sexual-assault rally, for instance. It came about after some students decided to protest the Committee on Standards' alleged decision to acquit an accused perpetrator of sexual misconduct. But when the Dean came hobbling down on crutches, entered the "safe space," and sat on the ground against a tree for a chat with some of the demonstrators, virulence and acrimony dissipated. At the rally, Liza Veto '93 felt compelled to sympathize with Pelton, who she said inherited a College disciplinary system in shambles. "I wouldn't like to be you," she told him. Pelton told the group he had just read their demands. "I think a lot of things seem very reasonable and a lot of things have merit," he said. "But I don't understand some of the specifics because they don't reflect how things actually work." And the dialogue began in earnest, lasting almost three hours. A day later, Dean Pelton released a statement of intent, delineating several goals the dean's office and the protesters had in common.

LONG GONE ARE THE DAYS IN which deans acted by the seat of their pants, doling out "dean's justice" and reacting to crises as they cropped up. Today, dean's justice is an invitation to a lawsuit. Pelton today is thinking about what possible crises may pop up in the future, so as to prevent the troubles brought about by short-sighted reaction. "I don't want to be the office that reacts to all the student crises," he says. "I have a vision that I think is congenial with the office's history; we are working in a partnership now with the faculty to effect that."

Pelton's readiness was evident in his handling of the sexual-assault issue. In an earlier interview, he said he thought the College takes allegations of assault very seriously. "We're already very aggressive in pursuing these complaints," he maintained. "But know that we're looking at possible changes and improvements." At the rally outside his office he was able to state: "There will be changes. I promised changes before this rally, and from my point of view it requires a review of all of the College's disciplinary procedures." Because of his foresight, he was able to join the activists' cause rather than play the part of the reticent (or, almost as bad, the caving-in) administrator.

When asked what potential problems he is examining at present, Pelton said, "The next issue is residential life. We have some wonderful residential-life programs, but when I leave I want to be convinced we have a residential community that's exciting, intellectually alive." (Pelton, if you haven't already noted, oftentimes sounds like President Freedman.)

"It has to have the type of richness and depth that I think it has the capacity of having," Pelton says of College housing, "so that a student's residence is not a retreat from academic life, but rather an important part of it."

Pelton very much shares Freedman's goals of allowing Dartmouth to become a more intelligent, intellectual environment for students while maintaining those aspects uniquely Dartmouth. Pelton doesn't think the school has far to go. "One of the reasons I came was because I thought we had such a head start in that regard," he said. Pressed for a specific time-frame, the dean postulated, "It'll probably take three to four years, at least, to effect."

When asked what aspect of his first year as dean of students went the worst, Pelton quickly replied, "I did not spend enough time with the faculty—meeting and talking, sharing my views." Officially, Pelton is a member of the faculty himself. He plans on teaching a course on eighteenthand nineteenth-century fiction this coming ing spring term. "It's your basic gothic romance stuff, but with a slightly subversive twist in that we will be reading subcanonical texts," Pelton said with a sudden burst of enthusiasm. "Except for Frankenstein, the works haven't yet found their way into the standard canon.''

He is qualified to teach. Pelton graduated from Wichita State University magna cum laude in 1974. He received his Ph.D. in English and American literature from Harvard in 1984. He held a series of administrative and academic positions in Cambridge before taking the dean of students position at Colgate in 1986. ("I still have this crazy notion of someday being a college president," he confided, adding, "I always thought I would have been a college president by now.") Outside of his religious upbringing, "education was the single most important value for me growing up," he said. He comes from a relatively middle class family—Exodusters who migrated from the South through Oklahoma and Kansas. Both sets of grandparents cam from farming families, one set from Oklahoma and the other from Arkansas. Education was always seen as valuable and inviolate, "the one thing no one could ever take away from you."

And he reads a lot. "My wife is a voracious reader—she keeps me on my toes," he said. Pelton only recently began dabbling in contemporary fiction. He reads Samuel Johnson "for comfort. Johnson was a very wise man; he knew a lot about the dynamic of human imagination and thought." Pelton enjoys re-reading parts of The Aenead in their original Latin every summer, although he admits his Greek has gotten a bit rusty for some of the more ancient classics. "I guess I'm a romantic at heart," he says.

When pressed on his own writings, Pelton said he thought he was going to write the Great American Novel when he was 21. Now, with a more modest, mature perspective, he admits, "I'm still fascinated by the essay, and I think I'm a fairly decent writer. It's not something that comes easily, but I generally enjoy it."

There has been little time for Pelton to familiarize himself with his surroundings and settle into such a holistic, academic perspective. In the first weeks of the term, Sigma Epsilon Phi joined four other fraternities in breaking ties with the College.

THE HOUSES QUIT THE SYSTEM in large part because their membership felt that delayed rush and the strict new alcohol policy made survival difficult. At the same time, some campus groups have attacked the Greek system for perpetuating everything from elitism to sexual assault. Thus the Greek issue has refused to die. Pelton, like most of the deans across the country, has his work cut out for him.

Before leaving Colgate, Pelton told The Colgate News that he had learned a lot working to solve conflicts between the university and its Greek system, but he added that he doesn't "want to have to go through that again for a while." Ironically, he told the Colgate newspaper he expected Dartmouth's Greek system to be less controversial. "One advantage I have had in coming here is that there's nothing new here," Pelton said more recently. "I have had to grapple with all of these issues before. From personnel issues all the way up to student-life issues, I come here with a sense of irony."

Pelton decided to handle the Greek issue (as he has many other issues) with the task-force approach. Pelton loves task forces. Spring term at Dartmouth saw the birth of four College-wide committees, all with catchy acronyms. Pelton brought two particularly new elements into these ad-hoc groups. He charged them to deliver recommendations within a specific (and short) period of time. And he stacked the groups with students. Both measures proved exceptionally popular on campus.

The policy he inherited was not so popular. According to statistics provided by the Office of Residential Life the number of men who rushed houses in the '91 and '92 classes was 61 percent and 59 percent respectively. Following implementation of delayed rush, the number for the '93s and '94s dropped to 45 percent. "Everything has bottomed out," said Marc Steifman '93, president of the Interfraternity Council, recently. "It hit us hard, but now things are starting to turn around. Pelton takes our input seriously, and things are looking up." Steifman, like the woman at the sexual-assault rally, found himself sympathizing with Pelton: "He has a lot of decisions to make. The toughest job he has is to respond to everything. So far we have worked well together."

But the Greek issue also provides Pelton with perhaps his greatest potential pitfall. After earning a reputation as a listening dean, Pelton may soon face the unsavory task of acting as the College's enforcer, curbing the independent fraternities' independence. Speaking to The Dartmouth late last spring term, Pelton said, "I am fully confident the five houses that defected will reaffiliate." This statement brightened the days of many a brother and sister on campus—until Pelton was asked to clarify just exactly why he was so confident the independents would return. The Dartmouth later reported he was referring to a proposal under consideration that would forbid enrolled students from living in independent houses, effectively destroying the independents' main source of income.

Since January, Pelton has been trying to lure the independents back with such carrots as promised changes and reforms of College regulation. Few expected him to bring out the stick to help prod the process along. He downplayed the issue at first, hoping the gentle prodding would be enough: "It's only under consideration, it's not imminent," he said.

But at the beginning of summer term, Pelton let the campus know the policy would take effect the following spring. Immediately, students began criticizing the decision. "It is an unjust and misguided edict that sets a dangerous precedent for every Dartmouth student, Greek or independent," said the unaffiliated Matthew Berry '94, a conservative columnist for The Dartmouth. "If the College is prepared to declare that it has an interest in regulating everything that involves students on or near campus, then it has proclaimed for itself a wide and intrusive sphere of influence over the most personal aspects of our lives."

Still, students are reluctant to blame their dean of students for the decision: "I really think this is a decision handed down to him," said Andrew Beebe '93, president of the Student Assembly, reflecting a commonly-held opinion on campus. "I think this smells like a Trustee decision in dean's clothing."

ANOTHER POTENTIAL POLICY sand trap: alcohol. When Pelton's task force on the new alcohol policy, largely composed of students, pointed out faults in the Shanahan-era policy, Pelton quickly said he will consider altering what he called the "implementation" of the policy.

Rahn Fleming '81, the College's alcohol counselor, notes that, as a new dean, Pelton is in a much easier position to analyze and possibly adjust the alcohol policy, having the dual benefit of enjoying a "honeymoon period" and learning where the old policy failed. "Pelton can take a look at the policy and make changes he sees necessary, maybe just as 'implementation reforms,"' Fleming said. "It doesn't have to be made into a whole big deal."

A committee task force backed by the dean's office recently examined the first year's implementation of the new policy, reporting several perceived problems. Biggest among the complaints was that the College was not consistently enforcing the alcohol codes. On one end of campus last Winter Carnival a Kappa Kappa Kappa fraternity party was raided by campus police after an alcohol monitor spied what he thought was the glint of a keg hiden in a social closet.

On the other side, Psi Upsilon fraternity had rolled out commonsource alcohol to be served to brothers during their infamous keg jump event. Dartmouth Safety & Security officers attended. Other complaints focused on the changing nature of the Dartmouth social scene and a possible increase in drunk driving resulting from the alcohol restrictions. A College survey showed that more people were drinking harder liquor before going out to socialize—a practice called "frontloading" that is potentially more dangerous than downing the same amount of alcohol throughout the night. And since parties with alcohol are practically forbidden in the dorms, an increased number of off-campus parties may increase the number of drunk-driving incidents.

With the reports still on his desk, Pelton plans to contemplate the information a bit more. He says he will act on it, if he feels compelled to, sometime fall term. While house presidents are not holding their breath, they report that the dean's office told them they may see the keg return to Dartmouth in the 1992-93 school year.

UNIFORMLY, PELTON'S COLLEAGUES have been impressed by his early success. The highest officials of the College, the Trustees, President Freedman, and Provost Strohbehn routinely consult him for dean's input they likely would have forgone in past years. At the end of the spring term, Pelton received a call from a highly placed administrator asking for some advice on how to react to the Rodney King rallies taking place on campus. Pelton told the administrator, "Just do what you feel you ought to." When later asked why he had sought out Dean Pelton's opinion, the administrator replied, "It was not just because Lee is black. I value Lee's advice greatly. I knew he would help."

President Freedman said he thinks the amount of respect Pelton has garnered in such a short period of time "is due to the force and stature of his personality." Freedman said, "He has exceeded all expectations. He has been spectacular. It's been a very difficult year, there have been issues of alcohol, of sexual assault, of fraternity disaffiliation—the way he has handled them is a measure of how spectacular he is."

When asked if Pelton was fated to be a college president someday, Freedman knit his brow and nodded. "He so clearly has the type of breadth needed in a college president. I just hope he stays here a very, very long time."

"He is still learning and evaluating issues, which you would expect in anyone's first year," Provost John Strohbehn said. "At least at the senior-officer level we are very pleased with the breadth of his knowledge and his openness to new ideas."

Dean of Residential Life Mary Turco concurred, adding, "I would describe Lee Pelton as a student's dean. He has accomplished a great deal in one year in terms of winning the trust of students."

"That's who I am," said Pelton: "The listening dean—and that won't change. I don't see myself as distant from students," said the man who spent nine years in Harvard residence halls. "I have some good instincts as far as what students want and need. We don't give students enough credit for their ideas."

Sitting on a bench on the Green Pelton said, "I want to be perceived as someone who is open and candid, not as someone who has all the answers—because I certainly don't."

Pelton has alreadyco-opted protestorswith his appearance of learningfront the students.

Ed Shanahansdecisions gave Peltonroom to maneuver.

One of the dean's firstchallenges is to bringhouses like AD back.

Tig Tillinghast is editor of TheDartmouth.

a thing or twoabout unpopulardecisions. Heimplemented asuite of them justbefore he left topreside over ChoateRosemary Hallin Connecticut.

have attacked thefraternity housesfor perpetuatingeverything fromelitism to sexualassault. Thus theGreek issue hasrefused to die.

in which deansacted by the seatof their pants.Today, dean'sjustice is aninvitation toa lawsuit.

professionaltrouble-shooters.Today theyformulatepolicies to dealwith racerelations andsexual assault

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

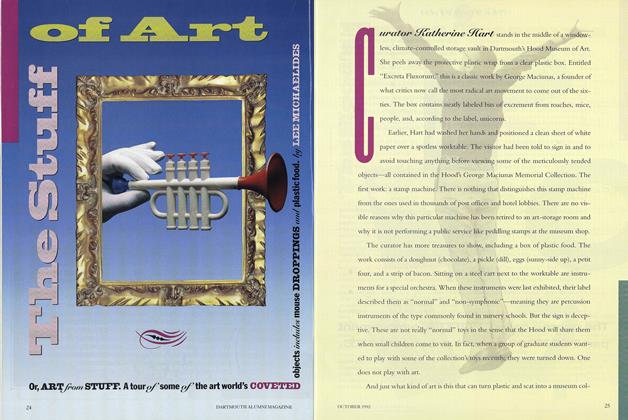

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Underground Curriculum

October 1992 By Tim Brookes -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleDid Something Happen in 1492?

October 1992 By William Spengemann -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1992 By Rick Joyce

Features

-

Feature

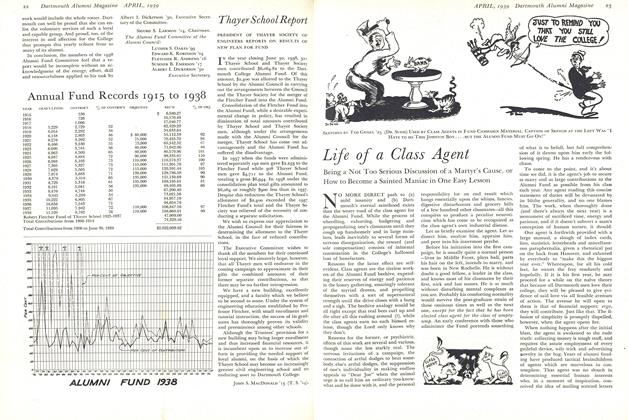

FeatureAnnual Fund Records 1915 to 1938

April 1939 -

Feature

FeatureAnd More

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPONG PADDLES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

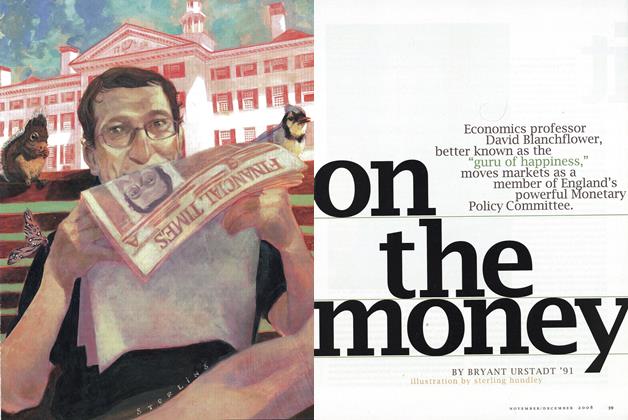

FeatureOn the Money

Nov/Dec 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAre Americans Saving Enough?

JANUARY 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Features

FeaturesJoseph Campbell, class of 1925

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Marley Marius ’17