Why didn't men's soccer live up to the soaring expectations? Perhaps it was just the nature of the game.

TWO YEARS AGO THEY WERE Hanover's darlings, a scrappy bunch of achievers who surprised the Ivy League and the rest of the college soccer world by marching through its schedule all the way to the quarterfinals of the NCAA tournament. They finally lost there, 1-0 to Rutgers, the eventual runner-up to national-champion UCLA. By the end, they had threatened nearly every page of the Dartmouth soccer record book, setting school records for wins (14) and goals (43) along the way, winning Dartmouth's first-ever outright Ivy League title, and finishing the season ranked eighth in the nation among all Division I schools. It was, as the sportswriters might call it, a season scripted in Hollywood, filled with the heroes and high drama that those scripts are filled with, and when the curtain finally closed on the most unexpected, longest-running show in town, the ending was the kind that producers and coaches dream about: Dartmouth walked off the field following the narrow defeat at Rutgers knowing that eight of 11 starters would be returning for the 84 next season, including a veteran eran defense and the strongest class of seniors ever to play at Dartmouth. There would be a sequel.

As a general rule, sequels are disappointing, and such was the case with last year's soccer season. Or at least it seemed so on the surface. Picked to finish in the top 20 in several pre-season polls, Dartmouth dropped its first two games of the season—as many as it had lost during the whole previous year—and went on to watch its Ivy League and NCAA tournament hopes dwindle and disappear. As the season wore on, crowds at the home games dwindled, too. The Big Green finished the 1991 season third in the Ivy League behind Yale and Columbia, with a record of 4-3 in the league, a mediocre 6-6-3 overall.

Onlookers openly wondered, "What went wrong?" Coach Bobby Clark had continued to say, during the season and after, that this squad was every bit as good as the previous year's, and that in many ways it was better. "In Ivy League soccer, especially with such a short season," he said, "people don't realize how fine a line it is." He, for one, was not disappointed. He thought his boys had played hard and well, and had picked up a few valuable lessons in the process. When asked after the season ended, Bobby Clark said that, indeed, nothing had gone wrong.

There were highlights, to be sure. The Dartmouth team played brilliantly at times, most notably in 3-0 routs of Vermont and Brown. They beat Penn at Penn for the first time ever, and gave up just two goals during one six-game stretch. Goalie Jesse Bradley '92 posted four shutouts against the Ivy League amd six shutouts overall, both school records for a single season. John Milne '92 finished off a tremendous career with an All-America (and his fourth All-New England) selection. Dartmouth was unbeaten at home, that strong class of seniors graduating with a remarkable 23-3-2 record at Chase Field. But the bottom line was the bottom line, and when the post-season tournament started in November, the 1991 Dartmouth team stayed behind, disappointed, perhaps, but with a clearer understanding of just how fine the line really is.

SOCCER IS A DEMOCRATIC SPORT. With few rules and no equipment needed beyond a ball and a goal, it is played from an early age in back alleys and dooryards and manicured stadium fields all across the world. It is wellsuited for boys and girls, men and women alike, and they don't have to be unusually big or strong or fast to be able to play. Like chess, it is a game that is very easy to learn but very difficult to play well. The more advanced the level, the more strategic the game becomes, and the more unpredictable. Unlike tennis or basketball, soccer is not a sport where the superior side can almost always be counted on winning. Games, for the most part, are played at midfield, with subtle shifts in momentum and field position indicating the dominant team. The outcomes are normally determined by a single goal or two, a defensive breakdown leading to a breakaway here, a deflected shot from close range there, a controversial penalty kick. With such a slim margin for error, intangible factors take on disproportionate weight: the home field advantage, the weather, the officiating, a bad bounce, a team's chemistry. In that sense, soccer is like a democracy, too. Talent is rewarded, but so is it, many times, overcome by those less talented who work harder or smarter. Teamwork is generally rewarded over individual efforts, but not always. Life, with soccer as with so much else, is not always fair.

The '91 Dartmouth season, if not a display of fairness, was a showcase of intangibles. There were early losses against nationally ranked teams before Dartmouth's freshmen had even arrived on campus. There was a 1-0 overtime loss at Yale, a game in which Dartmouth came up empty on four breakaways and Yale scored after 110 scoreless minutes when an offsides penalty went uncalled. There was a backbreaking match at Harvard which Dartmouth dominated but ultimately lost, and with it its hopes for an encore NCAA performance. "I can't say I was low after that game, because I don't get too high or low over wins and losses," said Bobby Clark. "But that was when we had to be realistic and say to ourselves that it wasn't going to happen this year. We thought we still had a chance after we came back after the Yale loss. Now there was no chance." He gathered his players following the game and told them always to remember how they felt at that moment, to know what it is to be denied.

Of Dartmouth's six losses, three were by two goals, three by just a goal. Each of the games—with just a few inches' difference on a shot off the goal post, with a changed referee's call, with a fingertip save going just under the bar instead of just over it—could have been different. And as the individual games went, so went the season.

Yale—whom Dartmouth played to a virtual standstill—won the Ivy League title and advanced all the way to the NCAA quarter-finals, finishing the season ranked number eight. Dartmouth lost just two more games in the league but failed to appear in any national post-season polls. The team was barely recognized in New England. Such a fine line.

YOU NEVER NOTICE LUCK when it goes your way," observes Bobby Clark. "Only when it's against you. Columbia and Yale could have said the same last year..." Luck was only one of the factors in Dartmouth's season. Dartmouth, having played the tough teams at home last year, played only six at home this year, nine away. How important was that? Several games were played in inclement weather, conditions that tend to neutralize talent. "It's not something that's easy to get a handle on," says Clark. "There are so many variables. One thing you can sense, though, is that when a team is hungry, more things tend to go its way. I don't know if it was because we had gone to the tournament the year before and were expected to repeat, or if going to Wisconsin wasn't the same kind of bonding experience that last year's two-week trip to Scotland was, or if we were feeling too much pressure—but something about the chemistry of this team was just a little off. There's an edgeover maximum effort almost—that you get when you're on a roll. When you're not, you're just shy of the edge, even when the effort seems to be there. We played hard and came back from a lot of adversity this year, but we always seemed to be working at it. We never put it into automatic."

Hearing Bobby Clark, my own experience with soccer echoes back to me. I played four years at a rural New Hampshire high school, on teams that were short on talent but long on work ethic. Better-schooled teams from Hanover and Keene dreaded playing against us because our field was less than perfect; we disrupted their style, took them out of their game. We loved playing in the rain. More often than not we beat other teams to the ball, and played hard even after they started to tire. And for some reasonmaybe because most of our players were from farms and poor country houses, and theirs were from comfortable housing developments—we played with more hunger. And, while hunger was never enough by itself, in our case, to overcome our lack of finesse and limited resources and bring back a state title to old Fall Mountain, we won more than we lost, and were a spoiler more times than some very talented opponents would care to remember.

It's odd that soccer has never caught on in America as it has in so many countries throughout the world. Few other games offer the underdog such a chance, the American dream of overcoming everything in front of you through the sheer strength of hard work, grit, and determination. But America, too, is a society built on images, and for most of America's real underdogs—the rural and inner-city poor—the glamorous images of N.F.L. running backs and Michael Jordan slam-dunks are the symbols of the American rags-to-riches dream. Soccer, my own high school team notwithstanding, is in this country a sport of the middle and upper classes. Hear someone talk of the "soccer boom" going on here, and the argument is usually based on flourishing youth programs in places like Connecticut and Maryland. American kids growing up with soccer don't learn it by kicking cans around a back alley; they are taught at soccer camps with the best equipment money can buy. Perhaps that's a reason for America's poor showing in international and World Cup soccer, where we compete against teams made up from the full spectrum of society, including the hungry end.

It's ironic that those same demographics allow Dartmouth and other Ivy League schools to play with the best soccer programs in the country. Since the bulk of the soccer talent pool comes from a segment of society that also places a high value on education, schools that emphasize academics have an advantage in attracting athletes. ("That's our selling point," says Clark.) Compared to sports like football and basketball, fewer soccer players are lost to the big sports-oriented universities. (It's the same reason that the Ivy League competes on the national level in sports like sailing, crew, and lacrosse.) "Those schools might have an easier time of getting to the tournament," says Bobby Clark. "They offer scholarships, they have lower academic standards, they can red-shirt freshmen, they are allowed to play a 22-game schedule instead of 15. But we get smarter, more well-rounded athletes, players who are more likely to be good leaders. And we've got no superstar ego problems. Players at Dartmouth are good workmen: they play a simple game of soccer and work together as a team. It's the kind of soccer I like."

Before Bobby Clark—a former standout professional goalkeeper in Scotland—arrived at Dartmouth seven years ago, a third-place finish in the league would not have been considered a disappointment. For many years, Dartmouth had struggled just to score goals, let alone win games. Clark inherited a team coming off finishes of eighth, seventh, and seventh in the eight-team league—and a program that had not shared an Ivy League title since 1964. By his fourth season, Clark had brought Dartmouth back to that level. He set a new school record with nine wins in a season—and then pushed it to ten the following year. His 1990 NCAA team won 14. Gradually, Dartmouth's men's soccer program has reached the level of the nation's elite. The schedule has no easy opponents, no longer includes schools from Division II and 111. Dartmouth no longer competes for recruits against Middlebury and Amherst; now it's Stanford and Columbia and the schools of the Athletic Coast Conference. "It's gotten to the point," says Clark, "where the best soccer players in the country who are serious about academics have to consider Dartmouth as one of their options."

While success breeds success, higher achievement leads to higher expectation, and Dartmouth soccer finds itself being judged on a different scale than it ever has been before. The dates of the NCAA tournament were included in the schedule handed out at the beginning of last season, a symbol of the new scale. But now the team is depleted, having lost its goalkeeper, its entire defense, and half its offense to graduation. Bobby Clark, perhaps not surprisingly, doesn't seem worried. In die fall a new crop of young players will arrive. They will be hungry and they will have something to prove. And for the first time in Dartmouth history, two high school All-Americas will be among them.

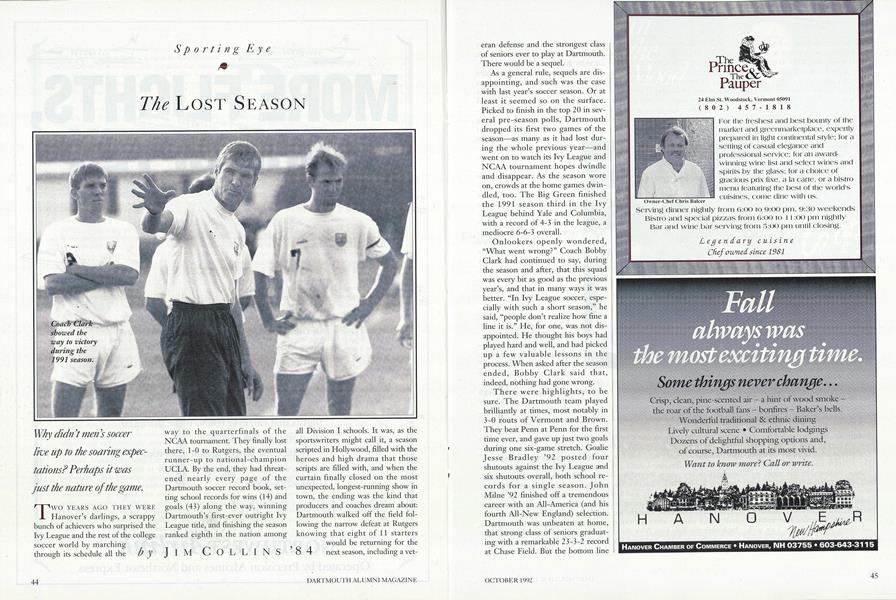

Coach Clarkshowed theway to victoryduring the1991 season.

After a sweet victory over Brown,they made it to the quarterfinals.

Jim Collins, a former high schoolAll America in soccer, is a contributingeditor to this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

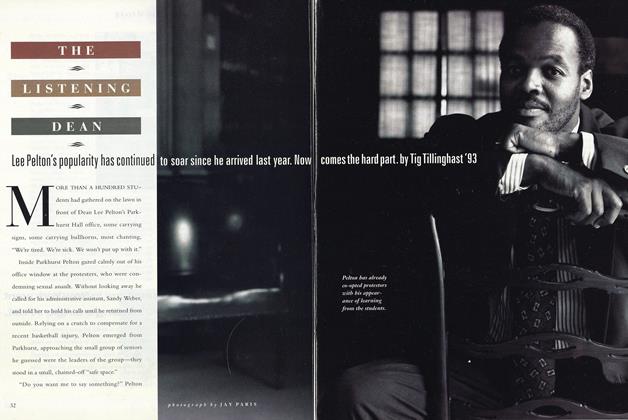

FeatureTHE LISTENING DEAN

October 1992 -

Cover Story

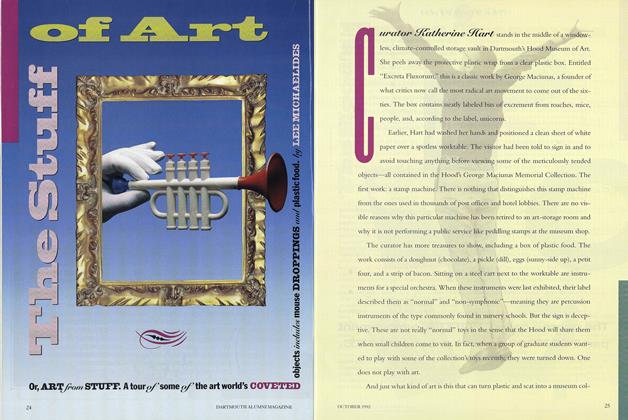

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Underground Curriculum

October 1992 By Tim Brookes -

Article

ArticleDid Something Happen in 1492?

October 1992 By William Spengemann -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1992 By Rick Joyce

JIM COLLINS '84

-

Feature

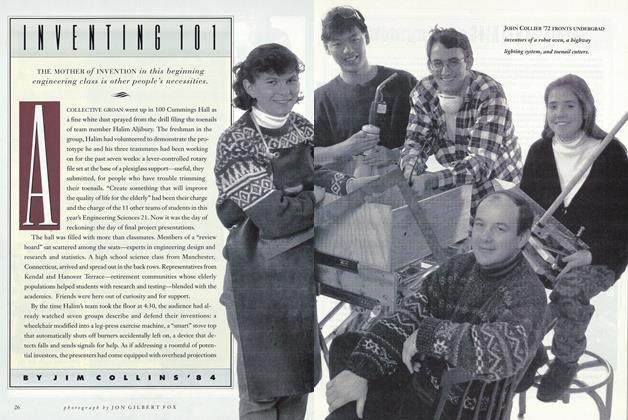

FeatureINVENTING 101

MAY 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Role of an Intellectual

JANUARY 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGILLIAN APPS '06

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

FEATURE

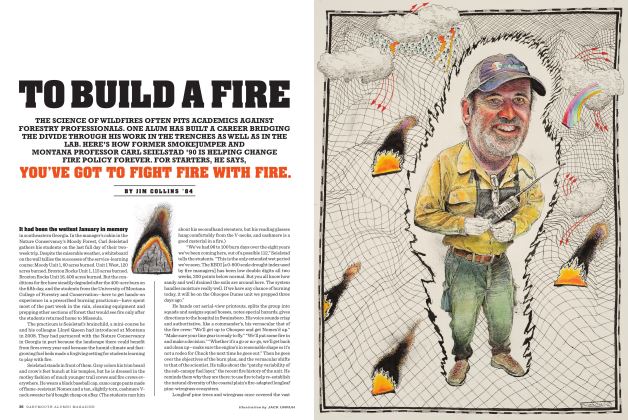

FEATURETo Build a Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

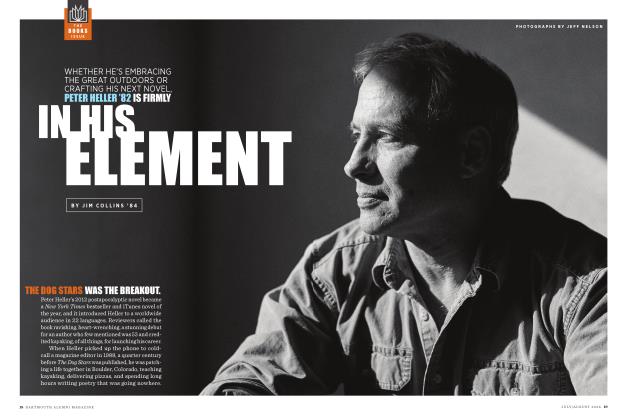

FeatureIn His Element

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Features

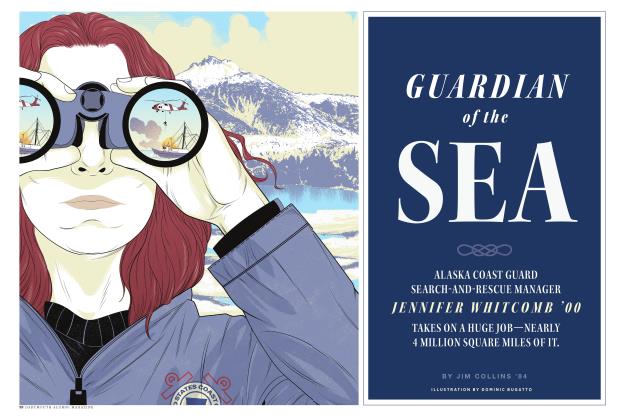

FeaturesGuardian of the Sea

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By JIM COLLINS '84

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLUB OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticleNOTED SPEAKERS ANNOUNCED FOR DARTMOUTH LECTURESHIPS

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleNew Term Opens

November 1944 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for

April 1960 -

Article

ArticleFriends of Robert Frost Plan National Membership

APRIL 1973 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

MARCH 1990