Studens are eternally obliqated to uphold a uast and hary tradition by circumuenting it. by Jim Briikes

with an institution that thrives on its own history—such as Dartmouth; such also as my alma mater, Oxford—is that the individual student can never forget that he or she exists against the dark, rich, massive background of the college's past, like a fly living on a Rembrandt.

As newcomers, especially, we find ourselves in danger of being overwhelmed, surrounded by faculty who literally wrote the book on their specialty, by alumni who have won prizes, set world records, and explored uncharted jungles, and by lawns as neat as billiard tables and buildings as grand and old as God. Yet one of the most remarkable traditions of such institutions is that over time students (and faculty) have collaborated to create a system both flamboyant and subtle, one that serves both to shore up our own identity and to maintain the cultural immortality of the institution. We have invented the underground curriculum.

I first saw a course description for the underground curriculum in the Cherwell Guide to Oxford. It turned up on the window-seat in my room in Pembroke College in my first week* at Oxford, in 1971, a thickish pamphlet published by the iconoclastic student newspaper. It was with a pile of dozens of more official handouts, brochures, fliers, and bundles of rubric, all of which I threw in a corner while I read stories of eccentric faculty, like the fellow who hid under his table and barked at students; tales of brutal revenge, such as when a dean was so hated that his students dismantled his car, carried it in pieces through the college lodge under the very nose of the porter, and reassembled it in an attic; historical insights, such as Gibbon's calculation that in three years at Oxford he uttered no more than a hundred words; and timeless jokes, like calling Jesus College on Christmas day, asking the porter, "Is this Jesus?" and then singing ''Happy Birthday."

Even at the time I dimly recognized it as not only a folk history but a recruitment drive, a challenge to live up to the institution's history of ten centuries of memorable eccentricity. Since then I've come to realize that the underground curriculum is also a survival guide, not only for the student but for the college. The underground curriculum consists of extraordinary acts of rebellion that are within the compass of anyone with enough originality and daring, and thus present those of us who'll never win Nobel prizes an opportunity for our own immortality. Individually, such acts grant us identity against the looming backdrop of the college; collectively, they prevent the college from either mummifying into smug self-congratulation or fading into ivy-less ordinariness. What keeps Dartmouth, in the words of the song, undying, is not exam results or illustrious alumni but generation on generation of students providing the material for more stories of things that could only happen at Dartmouth, or Oxford, or wherever.

actually Noughth Week. At Oxford, each term lasts eight weeks, and events are likely to be designated not by date but as taking place in Fifth Week, or whatever. The week after class end is known as Ninth Week; the week before they start is called Noughth Week, possibly the only usage of that word in the world, and a perfect example of underground language.

Cambridge, in other words.

The underground curriculum is what, more than anything else, helps us focus on the education that we, not the college, have chosen, sensing that without this counter-agenda we'll gasp and founder in the first semester, not matriculating but drowning. Its course requirements are made clear in the anecdotes that juniors and seniors tell to freshmen for reasons they themselves may hardly understand; and when I moved to New England, I was struck time and again by the similarities between good Dartmouth stories and good Oxford stories—not just the same kinds of student prank, or the same traditions, but the same respect for exactly the right kind of anecdote, told with the same irony, the same well-told smoothness, like a piece of college masonry, worn down to its essential elements with time and use.

(It doesn't matter a damn if such stories are apocryphal. The most important criterion is that on hearing a Dartmouth story you wish either (a) you had told it first, or (b) someone had told it about you. Two years after I graduated, I actually heard a student in an Oxford pub telling a story about a piece of underground performance art that I had carried out. It was one of the great moments of my life, better than any degree. It was like having History step down from his plinth and shake my hand.)

My researches at Dartmouth and Oxford suggest that the underground curriculum mirrors the official one, an upside-down thumb-on-the-nose mimicking, an anything-you-can-require-I-cando-bettering. For example:

underqround Art

ART IN THREE AND EVEN FOUR DIMENSIONS is quite acceptable. Oxford winters being relatively mild, I must confess that I can't think of anything to touch the Dartmouth 1950 Winter Carnival triumph in which the brothers of Sigma Nu sculpted two tons of frozen orange juice trucked in from Florida. The only remotely comparable achievement was the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan's act of underground performance art: when he was at Oxford he chartered a light aircraft and dive-bombed his college with empty gin bottles.

Any institution that aims to remain undying must also have a strong sense of color. Dartmouth Green. Harvard Crimson. Oxford Blue. Cambridge Blue, a sort of indecisive watery version of Oxford Blue. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute may be an excellent school, but if nobody knows what its color is, who the hell wants to go there?

underqround Dress Codes

HIS IS A MORE COMPLICATED subject than it seems, as we have to distinguish between eccentricity, which is a great asset and worthy of cultivation, and mere trendiness. It is a permanent blot on Dartmouth's escutcheon that in 1967 the college allowed Playboy to photograph Dartmouth men for a campus fashion article, just as everyone in Oxford winced when Tina Brown, who sat five seats ahead of me in Schools (q.v.), wrote an appallingly trendy article for Cosmopolitan about lifestyles of the rich and famous in Oxford: clothes, champagne, Jeremy's E-Type whose seats reclined enough to allow the 69 position. Tina is now, astonishingly, the editor of The New Yorker, having recently left Vanity Fair. They deserve each other.

Any college worth its salt, however, has sartorial eccentrics. Oxford had a student who would emerge from Balliol College every morning in top hat and opera cloak and cross the road to eat breakfast at the trucker's cafe in the covered market, and a middle-aged transvestite named Joyce who had shoulder-length white hair and wore miniskirts. Joyce was once arrested for mincing down the white line in the middle of one of the city's busiest streets, but the magistrate dismissed the case on the grounds that Joyce was "an Oxford character though nobody at Oxford, as far as I'm aware, had Dartmouth English Professors Jeffrey Hart's chutzpah and the requisite electronic know-how to operate a blinking bow tie.

underqround Architectural Studices

NDERGROUND ARCHITECTURE IS any structure whose form has nothing to* do with function—in extreme form, a folly. Dartmouth's Sphinx, a classy folly in all respects, is suitably shrouded in myth and legend that nicely combines the esotericism of Cleopatra with the banality of the water bill. Oxford, of course, has its share of follies. The Sheldonian Theatre, a strange D-shaped building designed by Sir Christopher Wren, who was apparently still drunk on the fee he'd been paid to rebuild St. Paul's Cathedral. Hartford College's replica of the Bridge of Sighs that doesn't even span any water. Keble College, accurately described as the world's largest Victorian public lavatory. Cambridge, of course, is almost all folly, except for one or two of the pubs.

underqround Phys. Ed

HARIOT RACING. CANE RUSHING. JEST" Tugs of war. Tobogganing in canoes—highly stylish and economical, as it represents two different underground sports in one. There must be something especially underground—or submarine—about water sports, in fact: not only does Ledyard Canoe Club have war-canoe races, but Oxford and Cambridge have punting, or poling around on shallow rivers in flat-bottomed boats like those used for duck hunting. Seriously. As is entirely appropriate, only the universities of Oxford and Cambridge punt, and Cambridge students stand at the wrong end of the punt when poling. I actually punted for Oxford against Cambridge in 1973. The contest involved sprint punting, relay racing, and jousting, in which two-person teams—one person poling, one holding a half-length pole topped with a wad of cotton batting—charged at each other like Ivanhoes. Cambridge was soundly thrashed, all the spectators were thrown into the river, and I ended up in the emergency room after treading on broken glass in the river bed. Who said we English play sissy sports?

underqround Lanquaqe and Literature

HE STUDENTS OF A TRULY GREAT institution save their most scintillating verbal displays for each other. Oxford graffiti is too various, clever, subtle, and extensive for me to do it justice here; suffice it to say that the most common graffiti appeared in almost all lavatories above the toilet paper: CAMBRIDGE DEGREES: PLEASE TAKE SEVERAL. (The exact same message can be found around campus at Dartmouth, though the Cambridge in question is slightly different.) My favorite graffiti appeared in a Pembroke stall. On the left wall it read PRACTICE FOR WIMBLEDON. SEE OPPOSITE WALL. On the right it read PRACTICE FOR WIMBLEDON. SEE OPPOSITE WALL.

Over time, the undying institution develops virtually its own language. Much of Dartmouth's has sprung up around inter-class rivalries: 'shmen; peagreens; and the bizarre habit of suffixing one's name with a class numeral even before one has graduated. This is very odd, and it can't be wholly contributed to Dartmouth's odd calendar that mixes up the conventional four years; it's either a form of premature aging, or a sneaky attempt to leapfrog straight into history.

As for Oxford, we had our own odd calendar. Terms weren't called Autumn, Winter, and Spring, or Autumn, Spring, and Summer, but Michaelmas, Hilary, and Trinity. All student transactions could be paid for by termly accounts known as battells, the word being so ancient that the university couldn't officially decide how it should be spelled. The dining hall was presided over by the Manciple, who seemed to have changed little since his less-than-glorious appearance in The Canterbury Tales; and scouts waited on tables at dinner and woke us in the morning by tugging open our curtains and uttering a brisk, "Morning, sir." (and if there was the happy coincidence of a tolerant scout and a willing girlfriend, "Morning, miss."). My scout, Stan, was living proof that humans had evolved not from apes but from lizards; we called him Piltdown Man. In Cambridge scouts are called bedders, but, then again, who cares?

underqround Medical Studies

HEN I THAT THROUGHOUT the nineteenth century Dartmouth was notorious for grave robbing, with two students being fined a total of $3,500 in 1895 currency, and that in 1877 a well-dressed skeleton appeared suspended between two flag poles, I thought for the first time in a decade about Horace Carter. Horace was a cadaver that (whom?) my friends Dave and Clive were dissecting in first-year pathology. The corpses are usually carefully divested of all prosthetic devices, but Horace had met his Maker still wearing his false teeth. Dave brought them into college dinner and surreptitiously dropped them into one of the soup tureens. During the long Latin grace (the second-longest in the university: "Pro hoc cibo, quem ad alimonium corporis nostris sanctificatum est largitus, nos tibi pater omnipotens..." and so on for two minutes) we kept an eye on the tureen, which, to our delight, was then brought over to the table next to ours, which consisted almost entirely of first-year lawyers—a smarmy and loathsome bunch. A good half-dozen of them were already eating their soup when the dentures appeared in the ladle.

underqround Drinking

RINKING HAS A CRUCIAL ROLE in the underground curriculum of any college, though I must give Dartmouth extra points for actually being founded on 500 gallons of rum. At Oxford, the Magdalen College Choir ascends the college tower at daybreak and sings hymns to the rising sun. Christianity has traditionally co-opted pagan ceremonies, songs, and stories for its own purposes; in Oxford, paganism struck back: an equally revered May Day tradition was the pubs' opening at dawn, and the challenge thrown down to us by our ancestors to get up, stroll down High Street (the High) to hear the warbling of the choir, then descend on a pub and drink it dry before breakfast.

underqround Civil Enqinering

HERE'S A NICE SIMPLE DIRECTNESS to the 1811 incident in which three students blew down one of the walls of the Dartmouth Museum with a small cannon, though at Oxford they wouldn't have been expelled—they'd have been made to pay for the wall. And Jean Kemeny is right to include in her memoir It's Different at Dartmouth the story of the brilliant undergraduate who in one night broke into 3,000 mailboxes with combination locks to prove the locks were useless. In my second year the city police designed an elaborate one-way system to reduce the colossal wear and tear caused by heavy traffic winding through narrow streets between 500-year-old

buildings. Some genius of a student studied the layout and realized that if during the night before the new system went into effect he moved one single Turn Left sign a mere hundred yards he could create a labyrinth which cars could drive into but couldn't drive out of. His spatial visualization was so far superior to the authorities' that they couldn't see how he had managed it; by 10:00 a.m.. the entire city was in gridlock, and the police had to take down every new sign and start again. Who is to say that student

shouldn't have got a first-class degree in something, even if only, as Rod Serling might say, in the twilight honors ceremony of the underground curriculum?

Tim Brookes, A regular commentator on VermontPublic Radio, has written for many publications, including Harper's, The Atlantic, and Marlow R.F.D

Dartmouth's Sphinx combines the esotericism of Cleopatra with the banality of the water bill.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

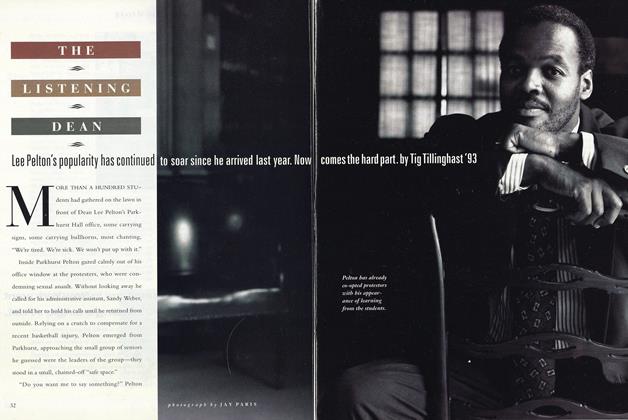

FeatureTHE LISTENING DEAN

October 1992 -

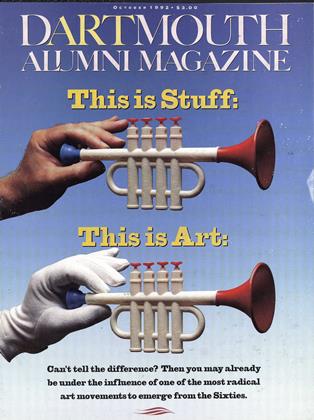

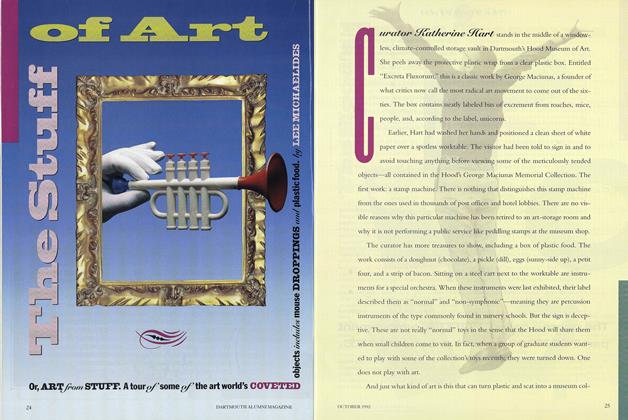

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleDid Something Happen in 1492?

October 1992 By William Spengemann -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1992 By Rick Joyce

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryTales of Dropouts And Bootouts Who Made Good Anyway.

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

Mar/Apr 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

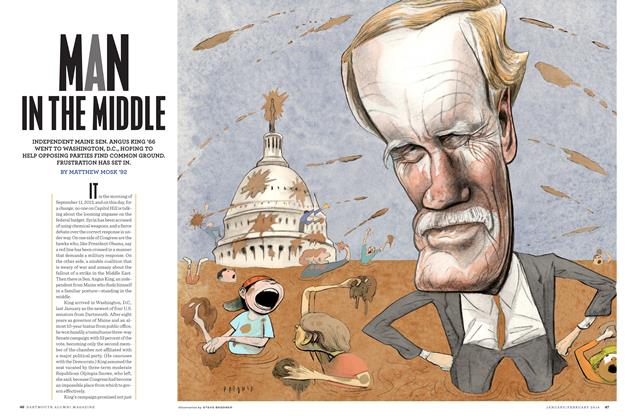

FeatureMan in the Middle

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

JUNE 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96 -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR.