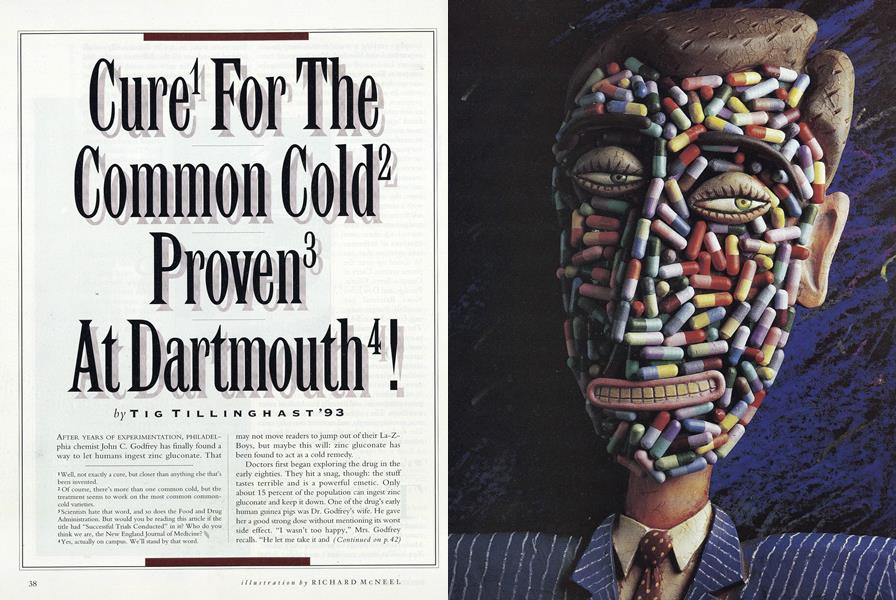

1 Well, not exactly a cure, but closer than anything else that's been invented. 2 Of course, there's more than one common cold, but the treatment seems to work on the most common common- cold varieties. 3 Scientists hate that word, and so does the Food and Drug Administration. But would you be reading this article if the title had "Successful Trials Conducted" in it? Who do you think we are, the New England Journal of Medicine? 4 Yes, actually on campus. We'll stand by that word.

AFTER YEARS OF EXPERIMENTATION, PHILADELPHIA chemist John C. Godfrey has finally found a way to let humans ingest zinc gluconate. That may not move readers to jump out of their La-ZBoys, but maybe this will: zinc gluconate has been found to act as a cold remedy.

Doctors first began exploring the drug in the early eighties. They hit a snag, though: the stuff tastes terrible and is a powerful emetic. Only about 15 percent of the population can ingest zinc gluconate and keep it down. One of the drug's early human guinea pigs was Dr. Godfrey's wife. He gave her a good strong dose without mentioning its worst side effect. "I wasn't too happy," Mrs. Godfrey recalls. "He let me take it and then just sort of looked at me with his eyebrows raised. I asked him what he was looking at, and then it hit me." After expelling the drug in the bathroom, Mrs. Godfrey told him she'd prefer the cold.

"I didn't know she wasn't one of the 15 percent," Godfrey explains sheepishly.

Dr. Godfrey, with the help of his statistician wife, came up with a solution: put the zinc in a lozenge, so the user never really swallows a whole lot of it, and the zinc can penetrate where it is needed most. The trick was to get people to use the drug in the first place. That meant disguising the terrible taste. Godfrey found that bonding glycine, a sugar-like amino acid, with the zinc partially disguised the taste without rendering the drug ineffective. Dr. Godfrey points out that other variations of zinc have been clinically tested as cold cures without success. "But they used flavoring schemes that molecularly sealed up the zinc, not allowing it to act as a medication."

The next step was to test this zinc gluconate/glycine batch. For that he called up John Turco, an M.D. who is head of Dartmouth's Health Services. When asked why Dartmouth, Dr. Godfrey responds: "When you need a couple hundred sick students to eat something, you choose a school way up north. Dartmouth students were great."

"There were all sorts of wild colds up there," adds Mrs. Godfrey. "We never knew what would walk in. It was great."

Since zinc gluconate has already been approved by the FDA as a vitamin supplement, Dr. Turco could offer the services of Dick's House without worrying too much about the risk to students. "Quite frankly, this is the perfect environment to do this type of thing," he notes. "And the financial support is helpful to us. Academically it's nice to get involved in these types of things, too."

So the scene was set—1991 winter bout number 1: Dartmouth Colds vs. Zinc Gluconate/Glycine. It was a long winter. Plenty of colds, illnesses, and assorted grimness to go around. The Godfreys were able to net 87 Dartmouth students willing to try anything to get rid of their ailments—even zinc.

Despite the drug's sweet disguise, it was universally condemned by Dartmouth students as bitter medicine. One student even dropped out of the study saying the taste was too much for him. Most study participants used the same two words to describe the flavor: revoking and nauseating, not necessarily in that order. Only half of the student guinea pigs were actually given the zinc gluconate/glycine lozenges. The others were given horrible-tasting placebos in order to place what statisticians like Mrs. Godfrey call a double-blind control on the study. In the end, a good three quarters of the students who took the zinc within 24 hours of feeling cold symptoms had their colds abridged by a fair amount—days in most cases. A few, those who took the lozenge immediately after feeling symptoms, prevented the cold from ever developing.

Beverlie Conant Sloane, until recently the College's director of health education, adds that a year later students are still coming back to see if Dick's House has more of "those grim cough drops."

One doctor at Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, however, was initially skeptical. Dr. David Smith, an epidemiologist who had worked on a similar study conducted years ago, believed that that particular kind of zinc produced no noticeable results. When the data came back from the Godfreys, Smith demanded a copy to verify the results. "They really converted me from a skeptic to a believer," Smith now says.

The initial success encouraged the Godfreys, but it did not mean an end to their quest. In order to market their product as a cold remedy they first must conduct a much larger clinical study and seek FDA approval. "We need to establish this with some hard numbers, but we can't afford to do the study until we sell some of the stuff," says Dr. Godfrey, who has been retired for several years.

While the Godfreys own the patents to the process making the zinc variant, the Quigley Corporation owns the marketing rights in most countries. A representative at Quigley says the company plans to market the zinc gluconate/glycine lozenges soon but just can't advertise them as cold remedies yet. "We're currently prodding the FDA so we can make claims," adds Mrs. Godfrey.

Dr. Godfrey warns not to be tooled by other companies making claims about zinc. "There are zinc sellers out there that are passing their product off as effective against colds, but they aren't giving any active zinc." In the meantime, the Quigley Corporation works on a cost-effective way to produce the lozenges so they can bring them to market to earn the capital necessary to do further research.

"Dartmouth was great for us," says Mrs. Godfrey. "You folks up there really gave us a great opportunity, and even did most of the day-to-day operations."

Would Dick's House's Turco be willing to offer up Dartmouth students in future medical studies? "If the right type of study comes along, sure, why not? This one was certainly fruitful—a potential cure for the common cold!"

Stay tuned for a future true story in this magazine: Thayer School of Engineering Designs Perfect Mousetrap.

Turco got Dick'sHouse involved.

Godfrey got thezinc to go down.

" There were all sorts of wild colds up there. It was great."

TIG TILLINGHAST is editor of The Dartmouth. He buttons up when the wind is free.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKnow Your Place

December 1992 By George J.Demko -

Cover Story

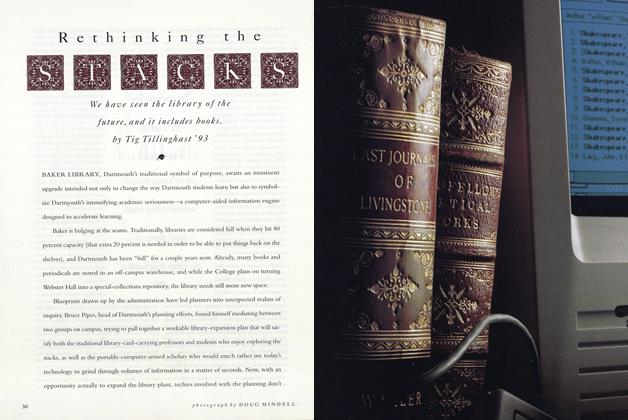

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ether Library

December 1992 -

Cover Story

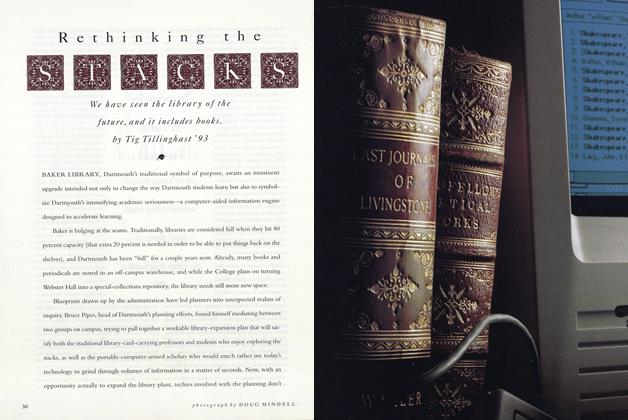

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWith Hard-bound Books, Who Needs Digital?

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTechnology Now and in the Future

December 1992

TIG TILLINGHAST '93

-

Article

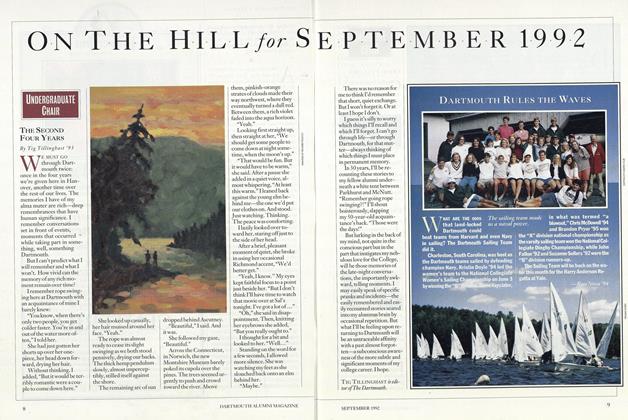

ArticleThe Second Four Years

September 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Article

ArticleOne Good Pull

September 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Article

ArticleA Leader of Gay Journalists

October 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Article

ArticleThe Anti-Doctor Doctor

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Feature

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93

Features

-

Feature

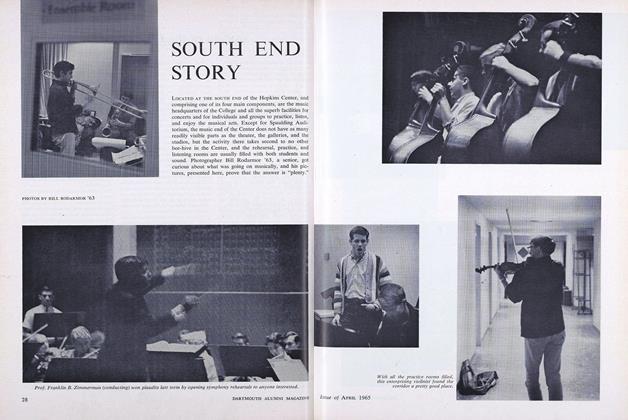

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

APRIL 1965 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTo die loving life

DECEMBER 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

FeatureNature Conditions Architecture

June 1954 By EDGAR H. HUNTER JR. '38 -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

MAY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Cover Story

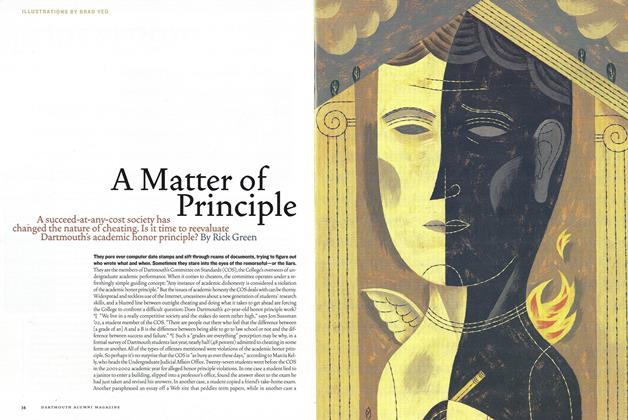

Cover StoryA Matter of Principle

July/Aug 2002 By Rick Green