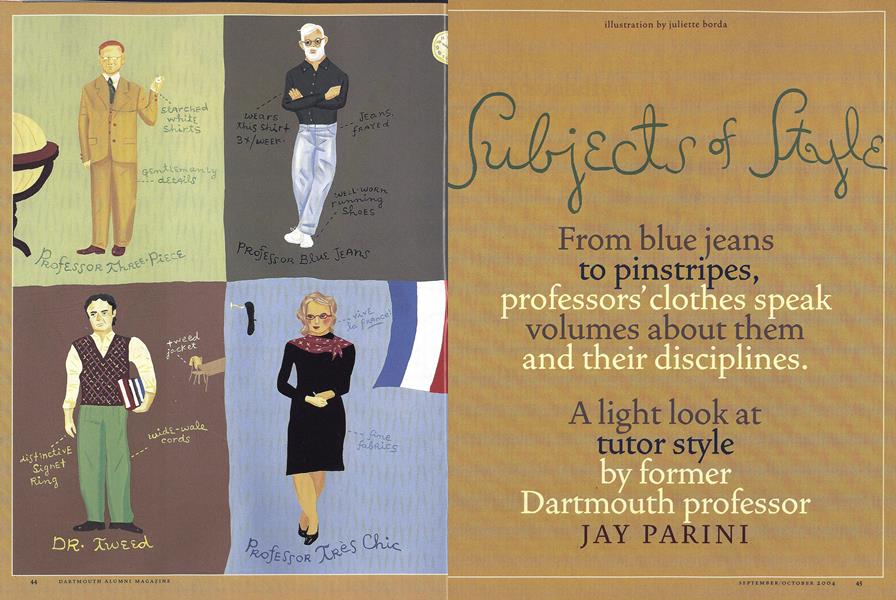

Subjects of Style

From blue jeans pinstripes, professors’ clothes speak volumes about them and their disciplines. A light look at tutor style by a former Dartmouth professor.

Sept/Oct 2004 JAY PARINIFrom blue jeans pinstripes, professors’ clothes speak volumes about them and their disciplines. A light look at tutor style by a former Dartmouth professor.

Sept/Oct 2004 JAY PARINIFrom blue jeans to pinstripes, professors' clothes speck and their disciplines.

A light look at tutor style by former dartmouth professor

Long after we've forgotten what our professors told us in college, we remember what they wore. Attire has its own syntax and vocabulary, and it says both more and less than seems apparent.

I remember, for example, the impression one English professor made on me in my freshman year at Lafayette College: He wore frayed and faded jeans to class, with a blue work shirt. On his feet were a pair of battered sneakers. It was a look that, in the mid-19605, was both startling and exciting. Here, I thought, was a rebel—someone who identified with the workers of the world. I also noticed that this professor always managed to find the countermeasures in any text, to isolate the subtle ways that authors undermined authority in their work, sometimes unconsciously. (It was deconstruction before Deconstruction.)

Another professor, an American historian, also caught my attention. He invariably wore an expensive suit with a matching vest. A gold watch chain was draped across his stomach, and his shirts were starched white, with old-fashioned collars. He seemed to have issued from a period when gentlemen were really gentlemen, and he spoke with an easy authority about the past and represented (to me, at 18) the establishment at its best. Once he invited me to his house for tea and caught me looking at a picture of Benjamin Franklin on the wall. "Ah, Franklin," he said. "He was my wife's distant relation." Somehow, it didn't surprise me.

Wishing to become a professor myself one day, I became a close reader of academic clothing—and of the scholarly ap- proaches and ideological affiliations of my teachers. Half con- sciously, I learned to tailor my own presentation (in papers and exams) to their fashions. Professor Blue Jeans would approve something that began: "Walt Whitman sang his own body electric, sinking his tongue and fingers into the sensual crevices of reality." Professor Three-Piece might prefer: "The foundations of American democracy were laid by a vigorous mercantile class, who resisted all attempts to impose limits on what struck them as their right to free trade."

Students tend, consciously or not, to respond to the expectations of their teachers. By definition in an experimental phase of their lives, they try on a pose, an ideology, a stance toward the world as they shift from professor to professor, from discipline to discipline. Eventually, they develop a style of their own, assembled from the haberdashery of their education.

When I went off to the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland (a junior year that lengthened into half a dozen in Britain), I found my ability to read the dress of my teachers severely challenged by the British class system. In due course, however, I began to understand the sartorial texts before me. While most lecturers (as in the United States, my teachers were all men) clung to traditional notions of dress, a few were clearly at odds with the system in some form.

My British-history tutor was an older man who was a member of the Fabian Society, a group of left-leaning activists and pamphleteers that had famously numbered Bernard Shaw among its ranks, and he identified with the labor movement. But he had also come to university teaching through the army and Oxford, and he was never going to stray too far from the traditional tweed jacket. So his sartorial rebellions were slight: He wore jeans, for example, when giving tutorials. His shirts were frayed at the cuffs and collars, and his ties were a living memorial to hundreds of splattered meals. The jackets themselves, made of tweed that resembled strands of iron, not wool, looked indestructible. He told us that he'd picked up one jacket at Oxfam, as if to say: "I am not giving in to fashion. I am not a consumer."

There was another version of that style, from the other side of the political spectrum. My tutor in medieval history wore iron tweed jackets as well, but his ties proclaimed affiliations with various old schools and colleges. (That more than 30 years later I remember he had attended Harrow and then Trinity College, Cambridge, suggests his care in letting me know his academic pedigree.) He owned the most solidly built shoes I'd ever seen: richly polished brogues. His trousers were corduroy, hugely ridged, auburn or deep green in color. He often wore a checkered vest under the tweed jackets. On his pinky was a gold signet ring—a sign of family distinction, real or imagined.

I recall fondly a photograph of Bertrand Russell—a hero of mine—that I kept over my bed at St. Andrews. In it the great philosopher (also a peer of the realm) wore one of those heavy English suits that declare a certain belief in tradition: a three-piece navy-blue suit with chalk stripes. Although Russell was a leading voice on the political left, his attire seemed to emphasize his ties to traditional British society. I always felt it was savvy of him to speak his outsider views from the inside.

iIn the early 1970s I attended lectures by Sir Isaiah Berlin, whom I would visit in his rooms at All Souls College, Oxford. He, like Russell, favored traditional pinstriped or dark suits. His formal black shoes were always polished to a high sheen, and he liked elegant silk ties. Coming from a family of Jewish immigrants, his place in the pecking order of British society had once been unstable, although he soon became a firm pillar of the establishment. Though he identified with liberalism, unlike Russell, he rarely dissented in a public way from what might be called normative opinion. His dress was, to a degree, defensive, his clothes signaling a strong desire to be regarded as a man whose authority was based on his classical education, his fine intelligence and his genuine-intellectual achievements; they also linked him, via pinstripe, to the world of bankers, lawyers and members of Parliament.

The British can also, of course, appreciate and encourage eccentricity. Several dons whom I knew looked like the male equivalent of bag ladies, though they vaguely adhered to the acket-and-tie tradition. Their clothes were unkempt, smelly and ill-fitting. One tutor of mine would stuff his pockets full of olives at cocktail parties, pulling them out one by one during tutorials, munching on the fuzzy balls unconsciously as he chatted about Keats or Shelley. There was no particular political statement that I could read there. Perhaps the disheveled look was just a way of saying: "I am an intellectual, deeply concerned with serious matters, and fashion bores me."

When a tie was missing, it was noticeable. One of the most famous literary critics of the mid-20th century—F.R. Leavishad made a name for himself by refusing to wear a tie at Cambridge. He had identified with the political left, as one might expect of a tieless man in those days; yet, a ruthless intellectual snob, he had also wanted to stand apart from the mob. His dustjacket photographs haunted me: the fierce gaze, the open neck, the high forehead. The intellectual isolation that he signaled echoed that of another Cambridge figure of a slightly earlier era, Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose casual dress—no tie, of coursecombined with an austerity of manner that frightened and intimidated a whole generation of students.

When, in the mid-19705, I came back to the United States to assume a teaching position at Dartmouth, I had to learn a whole new code of academic dress. Most of the professors, most of them men, wore leather hiking boots, casual trousers and plaid shirts. One got the sense that, after class, they might mow a field or repair a fence.

Finding an appropriate style of classroom dress for myself proved difficult. I missed the world of British academe and wanted to associate myself with the legacy of Russell and Berlin. My first major purchase in the line of clothing was a pinstriped suit with a matching vest. I wore that for about two months, until one day a student asked, without malice, "Professor Parini, why do you always dress like a banker?" Had he missed the allusion to Russell and Berlin? I tipped briefly toward the preppy mode, with Oxford-cloth shirts, blue blazers, khaki pants, penny loafers. But that felt inauthentic, and I stepped into jeans and casual shirts (but rarely hiking boots); I often wore a tweed jacket, but without the tie.

Several decades later, I find myself shifting among various personas with regard to dress. Sometimes I want to feel my connection to the 19605, to the radical politics that had inspired me as a student. I wear jeans on those days, and sometimes even dig an old blue work shirt from the closet. I also have a few billowing shirts, which I wear when I lecture on Walt Whitman. When I teach T.S. Eliot, I turn more formal in attire. Eliot, after all, was a London publisher who favored traditional suits with a bowler hat and rolled umbrella as accessories. By and large, I find myself most comfortable in something from L.L. Bean.

To a degree, a professor's academic field dictates style. I've noticed that scientists here at Middlebury College are casually dressed—a tie might get singed over the Bunsen burner. Foreignlanguage teachers, especially those with a European connection, seem to think of themselves as on the streets of Paris or Rome, even though they are living in a state where the cow population is larger than the human one. They often wear elegant fabrics, and—the women especially—are frequently dressed extremely well. In the arts and social sciences, one sees a mixture of tweed, jeans and casual shirts on the men; casual suits or skirts and blouses on the women.

Teaching is, after all, a performance art, and, whether or not we want to believe it, we're putting on a costume of sorts every day. We're sending countless messages, explicit and implicit, to our students, who are reading us as closely as they read the texts we assign; they (only partly consciously, I suspect) find clues to our attitudes toward the world, even our politics, in the styles we assume, and they often respond in their own personal ways; in their own dress, in the manner of their prose on papers, in how they picture the world of academics. It pays to think of clothing as a rhetorical choice, and to dress accordingly.

"Teaching is, after all, a whether or not we on a costume of sorts performance art, and, want to believe it, we're putting every day."

JAY (Henry Holt & Company),taught at Dartmouth College from 1975 to 1982. He is a professor ofEnglish at Middlebury College. This essay first appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

September | October 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

September | October 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

September | October 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

Interview

Interview“A Change Agent”

September | October 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Sports

SportsDouble Trouble

September | October 2004 By Chris Milliman, Adv’96 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92

JAY PARINI

-

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Jay Parini -

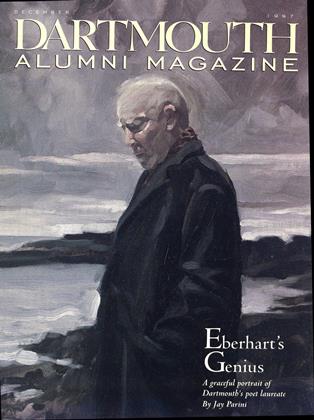

Front Cover

Front CoverFront Cover

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Full Mind of Richard Eberhart

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

Feature

FeatureCall Back

May 1998 By Jay Parini -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July/August 2001 By Jay Parini

Features

-

Feature

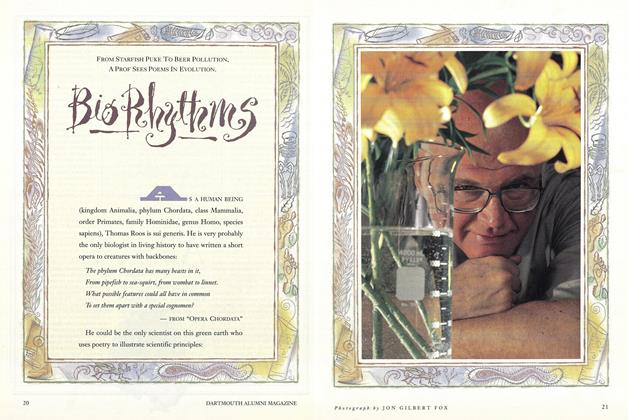

FeatureBio Rhythms

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May/June 2013 -

Feature

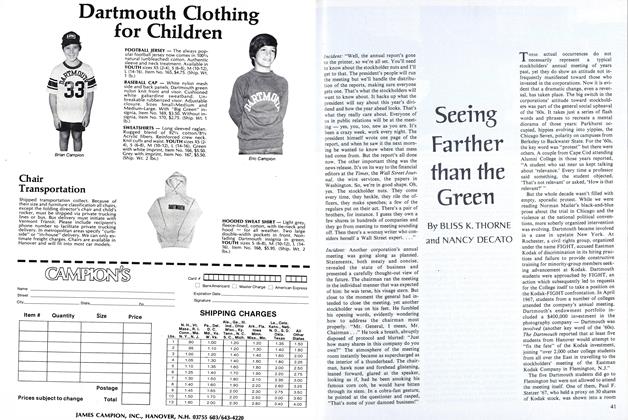

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

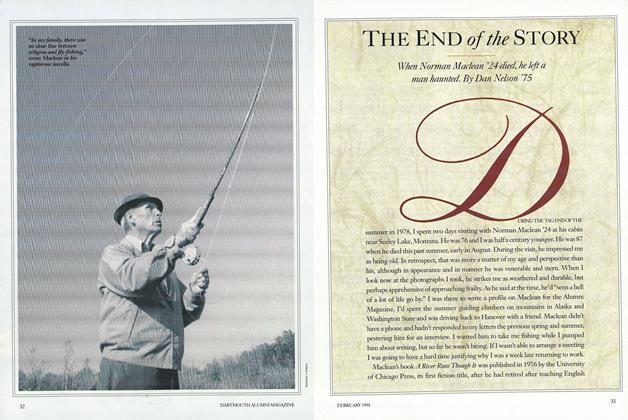

FeatureThe End of The Story

FEBRUARY 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

FeatureFirst

MAY | JUNE 2016 By Judith Hertog and Lexi Krupp ’15