When Peter the Great ordered a city to be built on swampland bordering the Gulf of Finland in 1703, he handed Russia challenges that would last centuries. Not only was he establishing Russian dominance in the Neva delta, previously held by Sweden, he was turning Russia westward after three centuries of Tatarimposed isolation from the intellectual advances of Europe’s Reformation and Renaissance. He was also turning his back on Moscow, Russia’s ancient capital, wrhich Peter hated because it repre- sented all that was ret- rograde about Russia, and also because as a child tsar he had wit- nessed the massacre of his mother’s relatives in the Kremlin and had narrowly escaped death himself. Even aestheti- cally Peter oriented his new capital toward the West, bringing in Ital- ian architects to create a city of right angles, great squares, spacious avenues, and pastel colors. Conspic- uously absent were the onion domes and crenellations that marked the Moscow skyline. Built on wooden piles and subject to frequent floods, St. Petersburg challenged the very forces of nature as surely as it chal- lenged Russia’s past and future.

Russian Professor Richard Shel- don is in his element when he tells this story of St. Petersburg. “I’ve been enamored of the city since I started going there in 1967,” he says. “It colors the work of so many Russian writers.” Since that first trip he has taken many Dartmouth students to St. Petersburg for foreign-study pro- grams. Even when he is in his Dartmouth Hall office, he never seems to be all that far from St. Petersburg. It crops up in the Russian books he reads and in his research on the writer Viktor Shklovsky, founder of Russian Formalism in the 1910s (which, ac- cording to Sheldon, was a movement in lit- erary criticism that focused on the text itself rather than on the writer’s life and time). And it is at the heart of a seminar Sheldon teaches to introduce freshmen to Russian literature.

Indeed, poets praised the beauty and gran- deur of the city during its first century, Sheldon continues. Early in the nine- teenth century, howev- er, Russia’s greatest poet, Aleksandr Push- kin, challenged that perception in his poem “The Bronze Horse- man,” in which he pre- sented the city as a symbol of brutal tsarist power. Following Pushkin’s example, successive Russian writers portrayed St. Petersburg as a city of doom.

“Gogol saw the city as a sinister place in which buildings had more vital substance than people. Gogol’s characters move like marionettes through the malevolent porticoes, caryatids, and balconies of the city,” Sheldon says. “Tolstoy depicts the inhabitants of the city as frivolous and unnatural. Dostoevsky’s titanic battles between good and evil take place in the fetid slums of Petersburg, where drunks proliferate and lechers prey on innocent children.”

Most damning of all, these writers depicted Petersburg as a city with- out a soul.

Then came the political upheavals of the twentieth century that tore at the city’s inhabitants and identity. Sheldon recounts the ordeals and the horrors: At the beginning of World War I, the name of the city was changed to Petrograd, as Petersburg sounded too Germanic. Shortly after the October revolution, the Bolsheviks shifted the capital back to Moscow, setting the stage for another period of Russia’s isolation from the West. During the ensuing civil war, White armies besieged Petrograd, and hundreds of thousands starved and froze to death. After Lenin died in 1924, Petrograd was renamed Leningrad. During the thirties, Stalin’s purges fell with particular force on the city, which he hated; hundreds of thousands of people were rounded up and sent to concen- tration camps. In World War 11, the Nazis besieged the city for 900 days. More than a million people starved and froze to death as Hitler, in grow- ing rage, vowed to kill every inhabi- tant and reduce the city to rubble; but Leningrad never surrendered.

With that endurance, something happened to Peter the Great’s city. “Out of its suffering was forged the soul that its peculiar origins had not included,” says Sheldon.

Shaped by adversity and bound to a past preserved in literature, St. Petersburg reclaimed its original name in 1991. Its inhabitants treasure the culture that their city embodies and preserves. People can recount the history of house after house: This is where Pushkin lived; this is where he bought his pastries... “You have the feeling Pushkin will show up any minute,” says Sheldon. “St. Petersburg is a haunted city: haunted by Peter the Great, haunted by the many thousands who died in building it, haunted by the writers who groped for its meaning, haunted by those who perished defending it in two world wars, haunted by the millions of its citizens who died in concen- tration camps—haunted by the past as it struggles to shape its future.” "

Through suffering, told and untold, St.Petersburg found its soul.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryProcrastinator’s Night Confessions of a Collegiate Insomniac

Winter 1993 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

Winter 1993 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleA Professor's Delights

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleEnglish Professor Jeffery Hart '51

February 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleEnglish Professor William Spengemann:

October 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHistory Professor Douglas Haynes

February 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWhy the Novel Matters

May 1994 By Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleTown and Precinct Elections

APRIL 1928 -

Article

Article"Quotes" from the Alumni

November 1937 -

Article

ArticleA Rare Student

February 1951 -

Article

ArticleKeeping the Faith

JUNE 1977 -

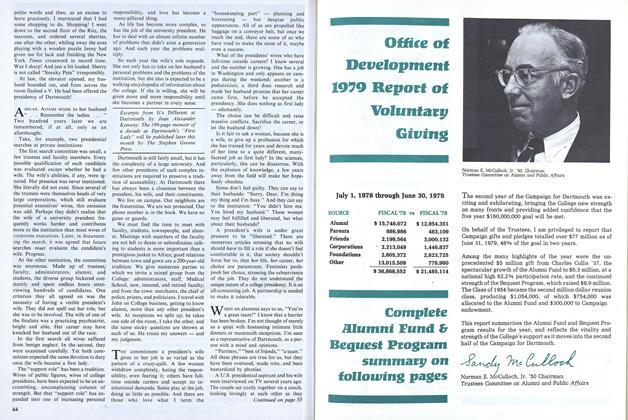

Article

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

NOVEMBER 1971 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38