The big jump is gone now, dispirited away in April mud and budgetary logic. There are those who loved it. Who can forget the soaring steel, the rattling descent, the urgency of flight?

Memory steps out on a platform higher than the golf course pines. Once on top the worst is over: you’ve quit the doubting and fretting, you’ve lugged your boards up 127 steps while other skiers clattered down. Now you deposit your skis on the icy planks, clean off the snow, pant a moment, then snug your boots into the iron toeplates and feel the heelsprings tighten down solidly.

You step in line. The next rider gets the sig- nal from someone down on the knoll. He cross- es himself three times, once more just in case. “Make it good,” he says, banging off the top onto icy tracks. He crouches, accelerating from 0 to 35 mph in three seconds. The curve to the takeoff lofts him into space. He twists, flails, drops in a clatter of skis, disappears.

Wait then while someone down there fixes a hole in the hill. You check your bindings, take some deep breaths, look around over the white peace of the hills—seeing almost nothing.

Your job is down there, straight down, down and up and out and down where you cannot see and up again— all in one motion.

At last the signal comes. “Make it good,” you say, to yourself as much as to the next jumper, and slide over the edge. Gravity hauls you down, incredible accelera- tion, a crescendo of roaring, the takeoff rushes up toward you. Every cell of your body is shouting: “Hit it right, right at the lip, between the spruce boughs. Up and forward and out over your tips.” Centrifugal force gladhands you into streaming air. The knoll flashes under, then the whole giddy panorama bursts open: the scarred hill, the upturned faces, the exact spot where you will land. Float. Float. Jolt! Catch your balance, strain to hold it through the dip, cheeks pulling down, colors going gray—then you’re up and out and gliding to a stop, all the the bells ringing.

Ten seconds. No other feeling like it on earth All skiers can jump. Some are born to be great jumpers. They are the ones who ride the wind and lean out on their luck.

—Philip Booth ’47 Poet, two hill records

Ski jumping is pure physics. As heavenly bodies must follow Newton’s laws, so must the earthly. Good jumping hills conform to these laws. There is a steep in-run to give the skier speed, then a curve to a somewhat hanging take- off. In air the jumper will go out and down in a parabola of fall. (He may enlarge the parabola by catching the air, surfing on it; or he may narrow it, obstructing the air.) Whether smooth or struggling or upside-down, he will fall 16 feet in the first second, 64 in two seconds. The landing hill must shadow this parabola down to the longest jump and then flatten out through the dip to a level outrun.

When Dartmouth’s big jump was constructed in 1921, last of a long line of lesser hills, it was designed for jumps of up to 135 feet. An 85-foot tower was erected beside the bowl to provide the necessary speed. Some nutty ideas also went into the design, improvisations by the Minneapolis engineer: a bell-curve at the top, a mid- section 45 degrees steep (too steep to hold snow), and a long flat run to the takeoff.

The steep section could be crudely fixed by building two wooden troughs for the skis, packing in snow, and putting the watering cans to them, but the racket would dauntthe deaf: bang—bang—bang into the troughs— Hell’s own uproar down the ice—wait—wait—wait for the lip. Even a blind jumper could tell the only safe place on that contraption was out in the air.

So in 1929, two years after Baker Tower went up, the big jump was rebuilt to the graceful lines we remem- ber. All troubles vanished. For 64 years the two towers stood as landmarks—glad reaffirmations of the two Dartmouths (the indoor and the outdoor) born together in Eleazar’s log-cabin college.

Ski jumping looks dangerous, but it is not, if the hill follows its physics and the humans pack the snow hard and smooth. Skiers fear sticky snow on the takeoff, gusty winds aloft, and soft snow or ice on the landing and dip where, struggling for balance, they may catch an edge and crash. For alt the spectacular falls over 72 years, the big hill at Dartmouth produced nothing more serious than two broken arms.

There are times, however, when even Sir Isaac wouldn’t know what to advise: as when Donnie Cutter ’45 sailed out and found one ski dropping off in mid- air. Great gasp from the Carnival crowd! In less than a second, Donnie invented his maneuver, placing the loose foot behind the other, makeshifting a landing, doing a contortion ballet in the dip, and riding it out all standing.

Or once when Omer Lacasse was opening the Carnival competition. Down he came from the top, squat- ting low and happy in the sport he loved. Just then a red setter full of Carnival spirits started straight down the landing hill. Omer couldn’t see the dog, nor could he hear the warning yells from everyone around the hill. Out he came—Omer was a beautiful jumper—and over the knoll; then he saw the wagtail dog running interference for him.

“Oh nooooo!” he sang out at this trick of fate, but his voice was lifting into a laugh. He landed alongside the setter, the dog transmigrated, and Omer rode to a stop shaking his head. “You never know,” he said, still laughing. “You never know.”

Aren’t you always a bit scared up there? Always. But exhilarated too. Maybe this time I’ll hit a perfect one.

Around home in Wisconsin I found a 1920 copy of the National Geographic which rhapsodized over “Winter Sports at Dartmouth,” all sorts of winter sports including ski jumpers doing somersaults on purpose. Sounded like an excellent institution. Father agreed. He wanted only to be sure the college laid on some educa- tion during the off seasons.

So, in September 1934, I disembarked at the Lewiston Station across the river, clumped through the old covered bridge, and entered Dartmouth. That was frightening, all those muscles running around, all that yelling.

President Hopkins—a calm friendly force of a man—enrolled me. After that it was books, classes, evade the predatory sophomores, and sign up for fall training with the ski squad. Through a long fall of dimming sun and changing colors we ran the hills, cleared trails, fixed jumps, and engaged in some disorganized brutality called soccer.

Naturally we freshmen were splattered with the blood of the Godlike upperclassmen, survivors of mon- strous cross-country marathons and insane downhill races. And we were told the solemn old legend: “Did you hear about the two guys who went off the big jump in a baby carriage?” “No—what happened?” “They’re still in the hospital.” (I went up to the hospital to learn the details, but the doctors only looked cross-eyed at me, and the nurses laughed.)

Everyone here skied four events, but I knew nothing of cross-country racing, nothing of the black magic of wax, and had never heard of slalom and downhill. Although I didn’t know it, I was joining a cavalcade of skiers already recognized throughout snow country. (Over seven decades, starting with John Carleton in 1924, Dartmouth would graduate 65 skiers to the Olympics.)

Work on the big hill was fun, a way of getting acquainted. But the weekends among die boulders and downed timber at Moosilauke were nightmarish. We were clearing up Dartmouth’s new downhill racing trail, “Hell’s Highway,” a two-mile gash down the mountain, in the middle of which was a long precipice obstructed, by islands of trees. It was vertical. At die bot- tom a “cowcatcher” of logs had been piled up to strain out the falling bodies.

This was crazy. Tip the whole state of Wisconsin up on edge, schuss it from the copper ranges in the north to Illinois and you’ll find nothing like Hell’s Highway unless you miss your turn at the bottom and sldd on through Chicago.

But—there was Sel Hannah ’35, our captain, a four-event throwback to the Norse God Ullr (with contributions from the Irish and Abenaki), a scholar, a poet. And Bern Woods ’36, a shy slender fellow, flawless in the air over big hills. As a freshman he had won the first National Downhill Championship on the old car- riage road on Moosilauke. These two didn’t seem like suicidal types.

And there was Otto, our renowned ski coach, Otto Schniebs, from Germany and the mountain troops of World War I. Four times wounded, Otto had come to this country an inspired prophet. He had his God: Saint Peter, and his reli- gion; skiing. He said that had the Kaiser been a skier, with only a “lousy Schtemm Krrristy” to soothe his soul, there would have been no war. Otto radiated divine assurance. He didn’t convert me; he rebuilt me from the junk parts left over from Hell’s Highway.

“Hokay, Dahveed, so you’re a chumper. Gut. Also dann a runner...”

“Oh no, Otto. Nix on that cross- country stuff.”

“...and a little slalom and downhill machen too, nichts?”

“Please, Otto. Not downhill. Not cross-country. ”

“Vat!— You vant to be nur Spezialist? Inschteed of real Skier? In der voods going, in der mountains going...all your life!”

“Well—all right, Otto—if you say so.”

“Dot’s der sschtuff, boy. Now you’re talking.”

The Dartmouth Carnival! It was the high point of winter— All that depth of tradition and community spirit.

—John Morton Middlebury captain and Dartmouth coach.

Impossible not to love the old hill. It had plenty of height and air for the long jumper, yet stayed close and easy for the youngster of ten or 12, determined to go off because “that’s what all the big guys did.” (He might barely reach the knoll and carom off for a second jump, but he’d be right back up all toothy eagerness.) It oversaw the midnight revelers riding the landing on toboggans and dining-hall trays. And it waited with special solicitude for the begin- ning skiers who, on a fraternity dare or determined to force a personal rite of pas- sage, slid out of a Sunday when nobody was around: Well?—lt looks awfully high— Other guys have—Yup—It’s crazy, but I will if you will—Well, you go first.

I remember when my brother Steve and I, during a break in exams—those severe upper-level disturbances—went out in crystal weather to jump, just to get our- selves back down to the uncomplicated earth. New snow had come overnight; we jumped soundlessly on silk.

And once, when a full moon blazed over the golf course, black pines all around, black shadows lacing the in-run. Well— Why not? To pour down the flickering slide, to lift out over that bald knoll and then drop into penumbra, falling, falling till the hill banged up under our skis and made us lurch for balance. That was good, as Frost says, both going and coming back.

In early February, when the sun began to warm, came the year’s great celebration; the Winter Carnival—the College bursting out of steam-heated exams, ice sculptures everywhere, dancing, hockey games, ski and skating races, Outdoor Evening on the golf course under an exploding sky.

At Carnival time, the big jump was nat- urally the central attraction; flags streaming from the top of the tower, cold hot dogs and cold coffee at the bottom, people from all over the North Country, dog fights, snowball fights, officials, police, and a shiv- ery trumpet call to herald each jumper starting down.

Pure fun. Here was one event everyone could walk or ski to, the one event which they could see top to bottom. Spectators were much too enthralled to be partisan. Whether they were skiers or not, they shared everything that was happening. They shouted for the classy jumper while he was still in air; they ducked for the poor fellow caught in an inter-fraternity snow- ball barrage; they groaned with the unfor- tunate who pretzelized himself in mid-air; and mightily they cheered for the impressed Harvardian facing his moment of Veritas in downhill boots.

Skiers from all over New England came to Carnival. Also, skiers from Wisconsin and Michigan, Seattle, Denver, Norway, Finland, even from Florida. After 1915 the great Red Birds of McGill were perennial favorites; in 1937 the Swiss universities sent over seven expert amateurs to race at Carnival and tour the western circuit. The Swiss may have won the Carnival, I don’t remember. Among such exuberant sportsmen, winning numbers added nothing.

Often the Carnival side shows were as exciting as the main event. In the twenties it was Bill Robes turning som- ersaults; the thirties, double and triple jumps were put on to please the crowd. (No one got skewered.)

But of all the extraordinary spectacles the big jump put on for us, none ever matched the day when two of the world’s best jumpers appeared: Birger and Sigmund Ruud of Norway. Birger had won three Olympic titles, Sigmund had set the world’s distance record at 283 feet. Compact bundles of energy they were, with broad smiles and that lilting-drawling Norwegian way of speaking. The hill was only half-size for them; no matter, jumping was for fun.

Five thousand people and not a sound when the trumpet called them from the top. Sigmund came first, rolling out into an effortless streamlined flight, his skis perfectly together, body curved over them, down, down, to land well beyond the hill record. The impact was so sharp, part of a ski tip snapped off. He rode on out, then turned to warn his brother, in shouts and laughter, not to go on them too hard.

Birger came tightly coiled: an explosion on the take- off, a high arching eternity in air, down and down to land 18 feet beyond the hill in the curve of the dip. His catlike landing made it look easy and his jaunty tail-wag christy showed us it was.

Those were perfect jumps—curves of high art drawn across a wintery Hanover sky which not even Leonardo could have imagined.

Farewell then to Carnival jumping, the heart of win- ter exuberances at Dartmouth. Something local and pre- cious. Yale has its incomparable Whiffenpoofs, Harvard its Head-of-the-Charles. At Dartmouth it was Carnival and convocation of the big hill.

It’s down now, the gorgeous length of that great jump junked—the first big college hill in the country, for decades the best, and, as it turned out, the last. Students of the future will not notice the dreadful emptiness among the pines on the golf course; little will they hear beyond some weird fable about jumping in baby carriages.

An outrage—tear down a national Monument! It should have been fixed, fenced, painted with immortal Dartmouth green, and hung with a plaque reading;

To youth and courage That once passed this way And will never be forgotten Harvard enthusiast

In 1980 the NCAA decreed that ski jumping was no longer a sport. Insurance costs were claimed to be the main reason, but that was a smokescreen. College insurance premiums have not dropped a penny follow- ing the elimination of jumping.

The one insurmountable reason was team travel. Many teams, unable to build their own jumping hills nearby, had to drive long distances in all sorts of weather to practice: UVM to Middlebury, UNH to Laconia, Colby to God-knows-where. Out west in the Rocky Mountain States the travel problem was much worse.

A final reason, well-known but never mentioned, was that, if a college or university were out to buy an NCAA championship, it had to import Norwegian jumper-schol- ars. By eliminating jumping, the school could, at one stroke, save time and money and free up athletic scholar- ships for other sports. The decision was inevitable.

One dissenting vote was cast during that crucial NCAA meeting: Dartmouth’s Seaver Peters ’54, a hock- ey star, and our athletic director at the time, argued that ski jumping after all remained a popular Olympic sport. He knew that jumping was a spirited part of skiing, which over nearly a hundred years had brought interna- tional fame to this small college. At Dartmouth at least, it called the community together and lit up the festivities like the autumn bonfires.

So ends the era, or almost. Four days before the crane and acetylene torches moved in, we held a last cel- ebration on the old hill. This was no solemn Requiem Mass, but a snowy sendoff, an enskyment.

Three winters of slop and frozen grass had frustrat- ed all attempts to use the jump; then in late March the hill winds blew us down an old-fashioned blizzard, piled up the drifts and brought out the skiers as though sum- moned by Richard Hovey himself.

The Ford Sayre gnomes came, the local high-school and junior-high jumpers rattled up in their vans, a bus- load drove over from Lake Placid; some older riders showed up, 54 years and younger, still with the gleam in the eye if wanting reflexes in the legs.

They came for one last jubilant salute, to tramp the hill hard, to lug snow in bags up the windblown tower, to fuss and fidget over their bindings, finally to climb to the lofty platform and test themselves, as it has always been, alone with their fears and hopes.

Warren drivers ’3B, up from Vermont Academy, and Ev Wood ’3B and I, all of the 1938 team, may have been the oldest skiers around. We were still good for marking distance and patching shell holes.

Many a youngster soloed that day. (They weren’t listening when someone told them that jumping was supposed to be dangerous.) One six-year-old, no bigger than a candlepin, kept shooting the landing and cussing because he wasn’t allowed to go from the top.

Chris Hastings and Joe Holland, recent Olympic skiers, were there for the celebration. They showed us that even on a 40-meter hill the new V-shape style (flat down on the skis like a hang-glider without fabric) works beautifully. Three times the old record of 165 feet was equaled. Then: haul down the flags, pick up the rakes and shovels, wind in the measuring tape, pass out prizes, drink a toast of Akvavit, and home to a lesser world.

Why do they come, the young, the old, with shining faces, lugging those heavy five-grooved skis? Because— Vox Clamantis—this is the most beautiful thing they have ever done, or are ever likely to do. ™

For 64 years the two towers stood as landmarks—glad reaffirmations of the two Dartmouths (the indoor and the outdoor) born together in Eleazar’s log-cabin college.

Ski jumping ispure physics.As heavenly bodiesmust followNewton’s laws,so mustthe earthly.

David Bradley teaches English literature and writing at DartmouthHe made his last jump on the Big Jump at the age of 60.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryProcrastinator’s Night Confessions of a Collegiate Insomniac

Winter 1993 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

Winter 1993 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleThe City Peter Built

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman

David Bradley ’38

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWith Hard-bound Books, Who Needs Digital?

December 1992 -

Feature

FeatureJOHN PFISTER

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureBRUCE SACERDOTE '90

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBROKEN CLAY PIPES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

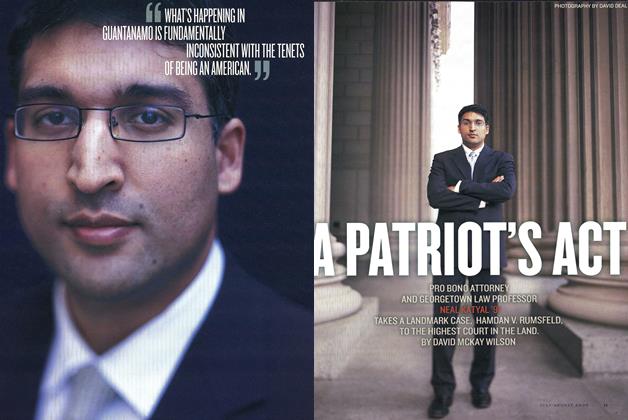

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

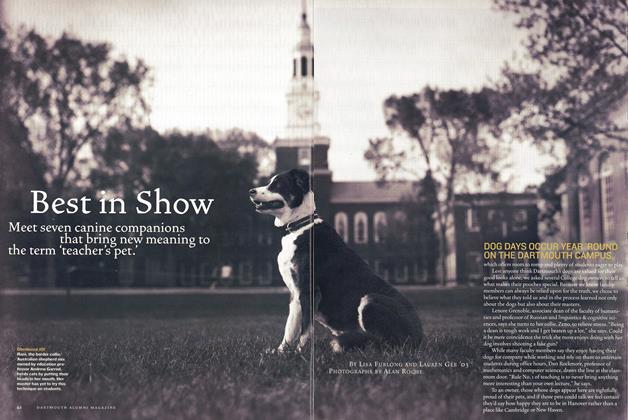

FeatureBest in Show

Mar/Apr 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03