Procrastinator’s Night Confessions of a Collegiate Insomniac

Winter 1993 Jane Hodges ’92A Clear MidnightThis is thy hour O Soul, thy free flight into the wordless,Away from books, away from art, the day erased,the lesson done,Thee fully forth emerging, silent, gazing, pondering thethemes thou lovest best,Night, sleep, death, and the stars.Walt Whitman

I DON’T REGRET THE WAY I SPENT MY LAST year at Dartmouth, trying to find something pleasant that would cheer me along until I was released, like a butterfly, from the cocoon of my own limitations. My senior year culminated in a great and traumatic confrontation with all of my insecurities about the world and my ability to be worldly in it: I was too busy, I was graduating, I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my future. My the- sis was two months overdue, I wasn’t having much fun, and two Ph.D.’s who loved psychoanalysis (one of whom claimed that a book called Nausea had changed his life) were after me with their grade books.

My procrastination transcended avoidance and became my reality—the reality that I had not spent my time doing the things I enjoyed most, like writing funny sto- ries about people who amused me and indulging in rela- tionships with intelligent, unathletic beaux who would accompany me in armchair philosophy discussions, on superficial dinner dates, to weepy B-movies, on barefoot strolls on blankets of pine needles.

Having exhausted all attempts to achieve pleasantness during my days, I found myself lurking, increasingly, in the evening hours. I occupied my lurking, as many seniors do, by writing a senior thesis. Mine lacked that autobiographical investment so present in most human- ities theses; it was just a little ditty about how a woman writer became a woman writer through the healing powers of an illegal and romantic love with a rich, foreign bachelor in the sensual, swampy plains of Indochina. I had no interest in romance or authorship the way my subject did, but I thought it would be a darned interesting study, being a thesis on a French woman writer, romance, and Postmodernism, and gen- dered writing and all that. I did not become an expert on the relation- ships between the plots of women fiction writ- ers and the movement of events in the plots of psychoanalytic theory, though. In fact, I handed in my thesis so late that my professors told me I risked not graduating, and that I was acting out a scene (they’re psy- choanalysts, see) in which I considered each of them a parent in a twisted triangle amongst them ... and me. Of course, what those Ph.D.’s didn’t know was that instead of becoming a literary analyst, I had become an authority on nocturnal culture. I had become, quite effortlessly, an evening artist, champion purveyor of the dark side of the campus, the unacknowledged mascot of the underworld of the collegiate procrastinator, the kind of kid who’d show up one day in a Paradigm, a Foil to the rest of the kids on the campus (the responsible ones) as a lesson and a threat to those who worked in the day, socialized regularly, and averaged 40 hours of sleep per week along with other stunning achievements which embarrass me so much that I cannot name them.

YOU MAY WONDER WHAT THE ALL-NIGHTER environment is like, and I’ll tell you. It is the environ- ment of coffee and books, angst and distraction, the deep dark murmur of the word “Catullus.” It is a small, cruel place with no cello music, unlike heaven. It is my thesis, my id, ego, and superego, all cross-dressing in my mind, lying in a mean harem, whispering ideas. I can only pic- ture it from outer space: the amorphous orb of the plan- et, the Rorschach splats of the continents, and on ours the thread of the Connecticut River snaking its way north, lapping along the town of Hanover, where in a flat square building, the one dot of light, I would find myself among harried students staring at computer screens, try- ing to put words into them, bobbing our heads like exhausted rag dolls.

The dot is Kiewit, the gate to the inferno of anxiety. Upstairs, the artificial light is as bright as the sun, and there are no windows. A whirring sound comes from an immense mainframe computer, the memory and brain of the entire campus, blocked on all sides by a mysterious clear wall whose clear doors have top secret locks. Outside of this great data beater, the veins of the building wander in a loop past a small cluster of occasional Late- Nighters tapping casually on computers in a small com- puter area. Students wander in and out, taking smoking breaks, printing sheets of their work, reading them. But you can’t be fooled by the ground-floor students. They are the socializers and paper printers, the e-mail readers, pizza eaters, and solitaire players. If you want to find the real Late-Nighters, the All-Nighters, the No-Doz push- ing, coffee-swilling, Shotgun Willy, pressure-cooking, thumb-sucking, son-of-a-professor term-paper makers, then you’ll have to go downstairs...

No one knows the real depth of the building, the depth past the basement floor where the walls are not asylum-white but something more inviting, a shade with the putty-white feel of an asylum waiting room. On one of the chalkboards, a desperate senior has usually left a Xeroxed note saying, “I’ve lost a disk titled ‘Thesis.’ If you find it, please call me immediately at this number.” The com- puters assemble like corn stalks in a field, the students sit at each, harvesting from memory, shucking like crazy. They have can- teens of water, like soldiers, and papers, grocery sacks of books, notes, and cans of cola. Their syllabi fly like paper airplanes. Their dogs lie flatulating and slob- bering at their feet. Behind their foreheads, the pulse of thoughts, love, intellectual ideas, and garbage filters from synapse to synapse, like water at a sewage water treat- ment plant, first dirty and common, then filtered, fresh and palatable, to an unfinished essay on the screen. As the hours pass, the students become androgynous with exhaustion, hairy and lost, returned to the cave state of the original world. Chairs creak on the half-hour, and audible groans happen. Hands are on heads, hands are on keyboards, hands are scratching and working away. Ids break free: one fellow stands up, raises one arm at a time, and sniffs, then sits down smiling, glad he uses Dial; a woman burps, open-mouthed; a wad of gum appears on the wall, and then returns to the mouth of its chewer; dip is dipped; hair is loose; and everyone is sweating.

This is the realm of the lost, the din of the hopeless procrastinator, that funk of exile and desire into which I fell, like Tantalus groping for grapes, for the better part of my senior year. There is no other place like this on the campus. No one pulls All-Nighters in study rooms that have couches, or even soft chairs. When we chanced to set up shop in the Tuck School’s study rooms on the all-night floor of the Murdough Center, the little capitalists left us a note that said, “Undergrads, go home!” I did my writing at Kiewit.

1 would arrive, regular as clockwork, around 8:30 p.m. I would sit at my corner computer, far from the mad- dening center aisle and the nervous babbling of other students, as if I were a geek hiding in the corner from other geeks. Aware that this was only the first shift, that set of hours when the majority of the chain gang was writing fitfully, hoping to escape by midnight, I would rearrange my personal affects. From my heavy bag I would take my dog-eared copy of The Lover, a twelve- pack of Diet Coke, Riffaterre’s The Semiotics of Poetry, a bagel, the theories of a British play therapist, and a fat book about the play therapist written by a woman named Phyllis Grosskurth. I firmly believed that by car- rying these books, putting them at arms reach, stoking the unconscious with a steady stream of soda, and writ- ing little messages on my palm, I would be able to focus, quite literally, on the tasks at hand. I would read and reread the blue ink that bled across my skin: do oralreport, write chapter 3, type resume, call home, pay Am Exbill. During the hours before midnight, I would stare at this palm and wonder about what kind of scholar I was. I would wonder whether Thomas Edison would be caught writing on his hand, “Go outside, invent elec- tricity” or whether Virginia Woolf might ever write on her hand, “Finish lighthouse novel” with the casual ease I would use to remind myself that I was two months late in finishing my epic work on “Melanie Klein and Marguerite Duras; Pre-Oedipal/Pre- Textual Constructions of Reparative Love.” I would re-read my favorite sen- tence from The Lover for inspiration: “I had never loved, thinking I had loved; I had never written, thinking I had written; I had only waited outside the closed door,” and conclude that I had never been a scholar, thinking I was scholarly, had never been in love, thinking I was loving, and that I was probably more like Captain Kurtz because I was writing the Congo.

In the seat next to me, my third roommate would con- tinue to produce prize-winning stacks of information on the androgynous world of George Sand in nineteenth- century France. She would regularly update me on her continual progress, and I would regularly picture her departure, the stacking and packing of her books, rearrangement of index cards, her congratulatory look as she tucked her disks in her academic sack. I would smile at her. I would buy her a soda. And when she left, she would be replaced by a corporate recruiting type who would rapidly reproduce a cover letter about the desire he had, beginning before puberty, to join either the advertising or financial fields. I would consider my thesis, the story of how a woman writer became a woman writer, and then consider that I really had no idea how this had been accomplished, and that, because I could not under- stand that, that I perhaps could never accomplish such a thing in my own life. I would go to the water fountain, to the bathroom, then back to the water fountain. I would print the draft I had written of the third chapter of my epic, then go upstairs to fetch it. On the way to the fetch- ing place, where the socializers stood relishing the fin- ished works they had come for, I would pause to stand in the back corridor. I would stand in the neon lighting, my pale face reflecting from the glass. I would think about my choices: M&M’s, Munchos, Chee-tos. Through the glass of the vending machine in front of me, the candies would dangle carelessly like Christmas ornaments. Sodas would hum on their shelves in the freon. I would put my money in, get my diet Coke and Chee-tos, and wonder, why was college not so simple—putting money in, get- ting something tangible out?

Downstairs, the time would hum on. Instead of work- ing on my thesis, I would begin doing strange things like writing poems about floods, stories about adolescents, or letters to people who were far away. I would print them, and tuck them under my arm. Midnight would strike, and the next wave would enter the basement, looking a bit more hairy, turned out from libraries or the reserve cor- ridor, wearing the shocked looks of people who’d been reading in a room full of sinister Orozco murals. I would stack my books in such an inconvenient heap about my chair so as to appear productive and busy, and to ward off any would-be chair stealers, and I would head out for my night-time stroll, a midnight ritual involving listening to my spring theme song, “Beast of Burden,” and going home to change my shirt or my lipstick or to get another book. Along the way, I would see the back side of the library and fellow thesis writers in their carrels, stack studiers packing up for the night. Passing the Tuck entrance to Baker, I would see the beau- tiful campus couples departing, climbing atop motorcycles or walking beautifully home to cuddle, curled like canned shrimp about one another, in a bed. I would con- tinue down Main Street and observe some smokers sitting outside of Sanborn Library, barefoot, with single books and notebooks in their laps. As I passed the Green I would see one of the regrettable objects of my affection loping across the field, a band of singing freshmen who were depending upon one another to walk, and swarms of moths. A woman who had rumoredly paid for back-thigh liposuc- tion would go speedwalking by in an aqua spandex outfit.

I would have felt solipsistic, a kind of feeling for which I lacked the vocabulary before college, if I did not come upon the Big Talker, one of my procrastinating friends, trying to light a cigarette in the breeze. He would be standing at the corner of Main Street, the lone empty road from a shoot-out town, reminiscent of bars with swinging doors, cowboys with guns, unidentifiable flying dust balls. I would know he was heading to Everything But Anchovies, a good place for reading Foucault and drinking hazelnut coffee till the place shut down around two in the morning. I would stand and protect him from the wind, so that he could light his cigarette, and feel giddy and delighted and mortally disturbed.

I would ramble down Main Street at no particular pace, and turn down Olde Nugget Alley, where I had success- fully hidden from Nausea more than once, when I chanced to observe him leaving tea time at the Hanover Inn. On School Street, I would find my apartment, go inside, change my earrings, call five friends, read my roommate’s Tarot cards from my special New Age deck, and then wait while she read mine. They would invari- ably contain the Death card (time to face profound change), the card of Ruin (time to get a shrink), and the Fool card (time to be as a child, and delight in die heaven on earth). We would order pizza. I would take a shower. I would think about a back massage, but not get one. I would have another diet Coke. Then, at half past two in die morning, I would don my favorite sandals and turn back toward Kiewit. Along the way, I would pass Thayer dining hall, dark and shut for the night, and then Massachusetts Row. An a capella group would be singing in a lounge, and in the next building, a clump of students would be watching David Letterrnan on tape or strange cult movies in the dark. I would watch them watch from afar, like a kid who’d celebrated Christmas watching other kids celebrate Christmas through a window outside of dieir house, only with anthropological indifference.

When I got back to my chair in the Basement, I would move my books and stare at the strange orbiting of my computer screen for a minute or two before I fell into near-sleep, that wolf-like state of brief napping, which, if you’re a wolf can get you up and running, but not if you’re a human. Because I would be too wired to sleep, I would daydream I was dreaming of sleeping, and that in this kind of sleeping I was resting, and that, after resting, I could rise and have a cup of coffee, and return, refreshed, to one of the chronic matters that remained scrawled in the palm of my hand: the oral report I had neglected to prepare on TheSemiotics of Poetry, a report in which I was to compare, contrast, and analyze two prose poems called “Bottom.” I would also half- dream of letters and a bell-shaped curve, C’s, D’s, and F’s, large leather chairs in the offices of deans, bound volumes, and denim work shirts in women’s prisons. I would dream I was Laverne of “Laverne and Shirley,” and that I was putting bottle cap after bottle cap after bottle cap on bot- tles of Schotz beer at the Schotz Brewery, and that this enterprise was supervised by a person I didn’t like very much.

THIS WOULD BE WHAT I WOULD DO ALMOST every night. Eventually, I would wake and return to my work, exhausted, but finally able to produce. But there were nights of special significance, and nights of serious adventure. I remember one night I awoke after about an hour, having not slept, unrefreshed and unaroused, only to see the second shift moving out, a small note from a sympathetic friend sitting atop my monitor, and, across the hollow and bombed-out remains of the room, the shadow of the Low Rider looming in the hall. You may have never known, in your time at Dartmouth College, a muse such as the Low Rider, a student who emerges at night, who could descend on a book like a buzzard bent on the last carrion on the face of the earth and carnivo- rously relish every last page of it until nothing remained but its bones and blood lying in a thumbed-through heap of a novel (the only way a warrior such as the Low Rider could produce a fine creative paper, ready just in the nick of time). There she was, arriving in her finery, standing royal, resplendent, like a peacock with a pinched nerve, her springy hair coiled upright in an Alfalfa-like geyser, and she was striding in for a starlight shootout with Willa Gather’s My Mortal Enemy. First she looked around at the cowfolk in the bar: she looked at me, she looked at the empty room, she looked at the ravaged carpet, the bags under my eyes, that violent shade of lipstick I wore just to stay awake, and then she paused, and said, “Looks like you need a coffee, kid.” And it was true. I followed the Low Rider up the back stairs of Klewit, and out to the mini-lot behind the darkened Baker stacks where her car, her par- ents’ shiny black Acura, was parked.

I would spend many a procrastinating evening with the Low Rider in that car, driving and talking, talking and driving, first skulking about campus, and then moving into die broader area of the Upper Valley: crazed quests for family-sized packages of Twizzlers from Purity Supreme, West Lebanon’s 24-hour grocery store; sugar rides to Dunkin Donuts; or my favorites, the rides into the middle of nowhere: river rides along Rt. 5 to Thetford where we once unsuccessfully tried to steal a road sign that said “Relationship Specialist, 0.5 miles”; rides over the darkened gorge and into the middle of Quechee; deer sightings near Etna; needless perusals of the sleepy town of Wilder; drives up the drive to a coun- try inn which will remain nameless, where guests would come out half-naked, hands shading their eyes against the high-beams of our strange black Miami-plated night car the way people in the movies shade their eyes from UFOs. These nocturnal escapes from daytime, reality, and Dartmouth, were reassuring because they confirmed what most procrastinators know that in avoidance lies truth, and the truth is, there are lots of things worth avoiding.

On this evening of serious adventure, this evening now well past 3 a.m., the first order was procuring a serious cup of joe. And we knew right where to get it, good and pitch black: Manchester’s Exxon, the only place on Main Street in Hanover open r 24 hours. We strapped ourselves into the chromium avoidance machine, and popped a night tape in the tape deck (we kept a stash which included Led Zeppelin, Kate Bush, Ugly Kid Joe, and the Janis Joplin album where she says in a hallucinogen- induced speech that a year is really only one long day and that, if you’ve got it today, why wear it tomorrow?). We pulled into Manchester’s, our heads moving up and down mechanically, our hair swaying wildly, our heads like the heads, maybe, of Dead Heads’ heads, and our faces crazed with music, insanity, and escape. We left the tape running, and walked into the store. As usual, the night cashier, a ski type of sorts, eyed us suspiciously. “You two, again?” he said. “Hey, why don’t you do something useful and sign this petition?”

We ignored him, and his litde petition for Ross Perot, too. Instead, we poured ourselves two black, black cof- fees, fetched a red shopping basket, and piled it full of brain food, the real stuff a jumbo bag of artificially fla- vored popcorn, Twinkles, Ore Ida microwavable french fries, sugar-free Orangina, sandwich bags of yogurt-cov- ered pretzels, Twizzlers, a Heath bar, and sugar-free raspberry flavored Bubble Yum. We brought it to the counter, and began to unload it. The fluorescent lights hummed. We were both pawing through our wallets when the Low Rider’s eyes fell on the magazine rack, and soon my gaze came to rest where hers did, right there, above the bodice-ripper paperbacks and cheap mysteries and and Michelin guides to New Hampshire, right on the consumer magazine section of the rack, right on the issue of Glamour we’d both been eying in the daylight hours for a solid week.

“Take it,” I whispered.

“No, you take it,” she whispered.

I eyed her big, black bag.

She eyed my jumbo denim deep-pocket jacket.

“I’m not going to steal it,” I said. “I have relatives in the Presbyterian ministry.”

“I’m not going to steal it either,” she said. “I’ve never stolen anything.”

The cashier’s face emerged from the ski magazine, and it looked into our basket, and it looked into our doleful raccoon faces, and it looked back into the ski magazine.

We began to sip our coffee and count out our money. Mr. Night Cashier began to ring up our items, Twizzlers and Twinkies and Heath bars, oh my, and popcorn and coffee and gum, and when he entered that last price, his hand paused above the Sub-Total button, and in that moment we all three became aware that there was no one but ourselves in this strange store in the middle of the night, and when the Low Rider and I both simultaneous- ly spoke into this void it came as something of a surprise; “Uhh...“ we said, “uhh...hold it! We want a magazine, too.” One of us dashed over to the rack and grabbed the issue of Glamour with the name of our most- wanted story emblazoned in bold pink italics across its cover, a story called “2,000 Virgins: Why they Waited.” We stood, bracing ourselves for a suspicious look from Mr. Night Cashier. But he just rang our vir- gins up, tossed them in the big brown bag with the brain food, and turned back to his ski magazine. Smiling, and percolating, we walked out. One of us pulled Glamour from the bag: “They’re procrastinators, too,” we said of the 2,000, and smiled, feeling that connection.

Back in the avoidance machine, we turned the tape to Side B, and drove south, and our eyes followed the twin paths of the car’s headlights down the road, past the strange swamp and the graveyard, through the perpetual- ly flashing caution light at the top of the hill, past a police car tucked off to the side of the road, and on toward West Lebanon. I rolled the window down, and I could hear crickets and night birds and the roll of the tires moving us away from Hanover. We sipped our coffee and ate Twinkies as the Low Rider drove, and I could have guessed where we might drive on this fine evening of avoidance, this evening when she had an outline due in a mere five hours, when I had an oral report and a thesis chapter and a life to plan in the next eight. We turned on to that long and lovely road that suggests the howling of lone coyotes and mysterious gunshots, the road that winds its way west along the White River, Route 4, home of the Hartford Diner and several garages where mon- strous Stephen King-like farm vehicles offer their dan- gerous profiles to the night. The clouds parted for us, and I remember that the moon was all white, and made a shiny milk moustache in the middle of the slow water.

I felt heavy-headed, and especially brave as I thought about signs and signifiers and how I hadn’t even begun my oral report about the two prose poems called “Bottom.” I had another Twinkie, and dipped it in my coffee, and the Low Rider and I talked now and then. We passed a farmhouse, and a bridge, and a small town with stores so small and general I have forgotten their names, whizzing by all of them at 80 miles per hour. We were delirious, detached, so close to orbit it was amazing. When it was well past four we decided it was time to turn around, but there were no shoulders on the road, and no clear straightaways, no easy way to turn back. We began looking for anything—driveways, rural roads, any place at the side of the road where we could change direction. We slowed the car to a good cruising pace and began to distinguish road signs, addresses, funny mailboxes, their red flags down. “Here,” one of us said, though we weren’t anywhere at all. “Let’s just turn around here.”

The Low Rider turned the car into a dirt drive that led up to a yellow country house, which sat next to a large dark barn with a big silo next to it, and as the car began its slow reversal, we looked out into the light at what was receding from us, and this is what we saw: a field of mud and cow dung, and upon it, not five feet from the car, a tremendous, snorting, flat-snouted bacon hog with a serious glint in its eye. Behind the hog there stood another hog, and behind that hog another just like it, and soon we saw that beyond our car’s beam of light, just beyond our line of vision, there was an entire fam- ily of bacon hogs, all snorting and chomping before us, wide awake, as if they had been waiting. The Low Rider screamed, and I began to laugh hysterically. The theme from “Jaws” played in my head.

“What could it mean?” she said.

“I don’t know, I don’t know,” I said, shaking a bit, like Nancy from “Sid and Nancy.” “It could be a sign of The Devil.”

“Maybe we should cut the engine,” she said. “What time do you have?”

“Time to leave,” I said.

And so we did, not knowing why those pigs lay in wait for us out in the Vermont mud, or whether or not we might remember this evening, though, as I think back on it now, I can remember it all perfectly well, can rewrite it even, as an evening seen from outer space, where the White River might resemble a dark soft brush stroke through a valley, a river paralleled by a road that ran East and West and seemed to stretch forever, unfin- ished. Down among this landscape one car, a tiny black dot crawling like an ant along the lip of the river, would come to stop at the edge of a farm. And in the matter of minutes before I fell into a true and sincere sleep in that car, right there, where I had screamed and laughed 'with a good friend, survived moral dilemmas, shared snacks, the violent music of killers and singers, the confessions of virgins, darkness all around, the sighting of unslaugh- tered pigs, work waiting, professors waiting, our whole life waiting for us, a flicker of awareness would come: there remained a few good hours before the sun, and all my work lay before me. “

tccA

tock

tleAy

tock

Jane Hodges, a former intern at this magazine, is currentlyin New York, preparing to attend a graduate creative writ-ing program and avoiding making a major career decision.She turned this manuscript in, we are sorry to report, almostexactly one year late.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

Winter 1993 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleThe City Peter Built

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman

Jane Hodges ’92

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTo Keep Pace with America

APRIL 1966 -

Feature

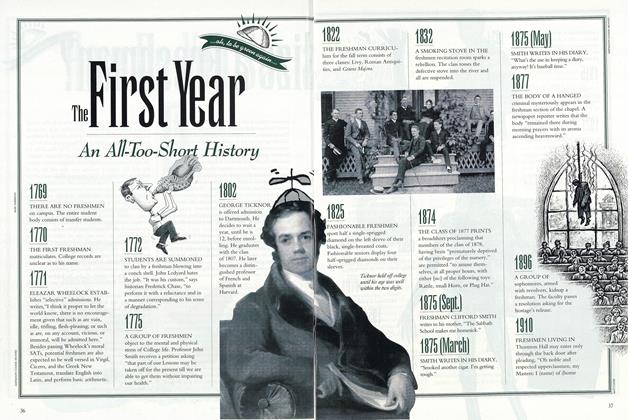

FeatureThe First Year

September 1993 -

Feature

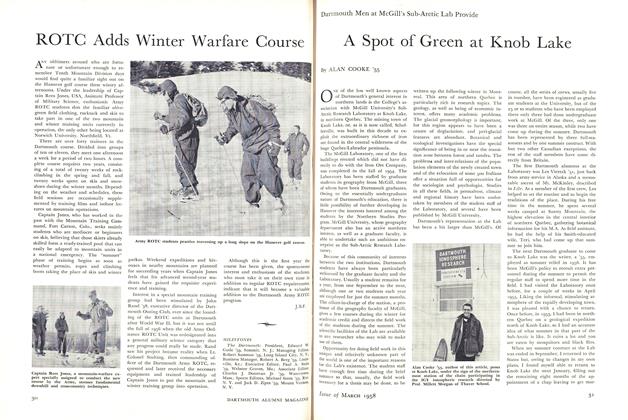

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Feature

FeatureSUBJECT: HALF OF HUMANITY

June • 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Cover Story

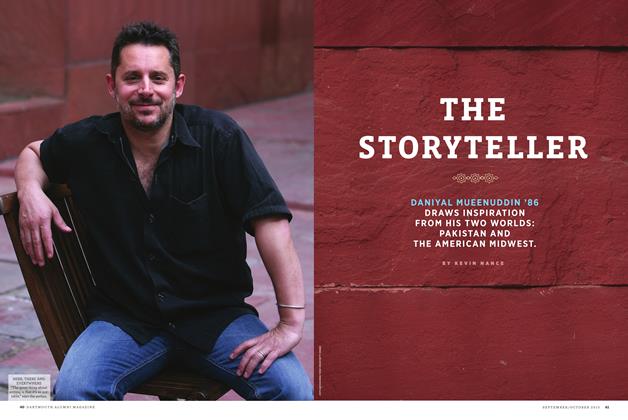

Cover StoryThe Storyteller

September | October 2013 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

FeatureTestament of a Teacher

February 1954 By ROYAL CASE NEMIAH '23h