To see how societies work, watch how they play.

HERE'S A QUESTION for you sports fans, you who always read the sports pages first or turn on Sports Center before turning on the coffee maker. Why do sports have such a hold on you?

Because you need to know how your team is doing? How the big game turned out? How the competition stacks up?

"Well, OK. But why?

Because you love sports?

OK, but why?

If you find these questions annoying, you've just proven a major point. Dedication to sport is one of the enveloping myths of our society, something we buy into even if we can't say why. As the British anthropologist Mary Douglas says, myth is an axiom about ourselves that needs no proof. We simply accept it.

But Ray Hall, a self-described "tennis nut" and sociology professor who teaches a popular course on "Sport and Society," says it's possible to penetrate the myth by analyzing the place of sport in human life. "The sports we play and the way we play them reflect society," Hall asserts. "Sports capture the core values of a society, reveal contradictions that may not be so easy to see in other realms of social life, and add to the very cohesion of society."

One explanation for why sports are so able to carry the societal ball is that they lock into a feature of human nature. Arguing that humans are inherently playful, the Dutch historian/philosopher Johan Huizinga contends that Homo Ludens "playful man," more aptly describes the species than Homo sapiens, "thinking man." According to this view, the need to play extends far beyond childhood and can be satisfied directly by doing sports or vicariously by watching them.

Indeed, as any real sports fan knows, spectating isn't passive. It gets the adrenaline pumping, the emotions surging, and most importantly, the imagination jumping. "We engage in fantasies internal play when we watch games," Hall says. "We project ourselves onto players. We can become Muhammad Ali floating like a butterfly or fantasize what it would be like to have the extraordinary skills of a Tiger Woods, or a Michael Jordan." We believe in their ability and by extension, ours. When our team wins we picture ourselves as winners. Or, sharing defeat, we vow to win next time.

There's no surprise why our spectating fantasies play out the way they do, Hall says. They take shape from the democratic and capitalistic core values American sports encompass: group goals, individualism, hard work, competition, and success. Baseball is so quintessentially American-like apple pie in motion because, says Hall, "it addresses two seemingly opposite core values, teamwork and individualism. You saw Lou Gehrig or Babe Ruth achieving individual feats, but their effort was for the team, too."

In this country sports constitute an arena in which individual dreams really can come true. "Sports is one of our most level playing fields," says Hall, choosing his metaphor carefully. Hard work can extend or even compensate for individual ability. In sports you don't even have to be born into the right class to excel. Not that every field has always been level. "For example," says Hall, "social barriers long kept African-Americans and other minority group members out of such country-club sports as tennis and golf. Increasingly, though, individual talent is what matters most." For that we can largely thank the fans."Spectators want to see the best," says Hall. "It's part of the American passion for winning. As Vince Lombardi told us about ourselves, 'Winning isn't everything. It's the only thing.'"

It's not the only thing everywhere. "Many societies frown on individualism and competition as uncooperative and disrespectful. They view the goal of sport as parity making sure that everyone wins," says Hall." In highly stratified nineteenth-century Britain, membership on a university or public school athletic team was what really counted. The goal, especially for the sons of businessmen during the Industrial Revolution, was social acceptance into the realm of the elite. Playing was winning, regardless of the outcome of the game.

In fact, says Hall, Homo ludens have always brought a variety of values and purposes to sport. From earliest times adults played out their skills and abilities some linked to food-getting skills, others to warfare—in casual displays, friendly exhibitions, or formal contests, often with a purpose that went beyond fan. The ancient Greeks began the Olympic games in 776 B.C. to honor the god Zeus. The original display of extraordinary equality, the Olympics were open to all Greek men, regardless of social standing. (Legend has it that a cook won the first footrace.) The Greeks prohibited women from the Olympics. But predating Title IX by more than a millennium, Greek women competed in their own Heraean games. Both the Olympics and Heraean games embodied the Greek principle of striving for physical beauty and grace. Roman sports, on the other hand, valorized war and power. Romans flocked to gladiatorial battles that pitted swordsmen against men armed with nets and tridents, animals against men, the more uneven the competition the better, with slaves the expendable combatants. In medieval Europe, class stratification governed sports. Jousting, for example, was the province of the aristocracy. So, too, court tennis and that most plebeian of modern sports, bowling.

At Dartmouth Homo Ludens has always played hard and worked hard. Even as Eleazar Wheelock looked down his Puritanical nose at any activity that was not utilitarian, students canoed and skated on the river for fun and innovated free-for-all ball-games on the Green. Students have always been the impetus for sports at the College, plunging the entire campus into "whole division" football games in the early part of the nineteenth century, and, starting with baseball in 1866, organizing teams as intercollegiate competition swept the nation in the second half of the century. Sports cross-cut social stratification here in much the same way they did in Britain. Acceptance on the team meant social acceptance. But the Vince Lombardi difference was already in evidence. In intercollegiate competition winning mattered. Even today, as students increasingly engage in sports for their own fitness ("The elite has always played, not just watched sports," comments Hall),they still take notice of the Ivy championships. "You can't even get tickets to men's basketball when they're on a winning streak," Hall says. "That's why I buy season tickets."

So, sports fans, go ahead and cheer. Dive into the sports section. As ever-playful Homo ludens you're just doing what comes naturally.

A front View of DARTMOUTU COLLEGE,CHAPEL,& HALL.

Senior editor KAREN ENDICOTT likes to catchthe final two minutes of televised games.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

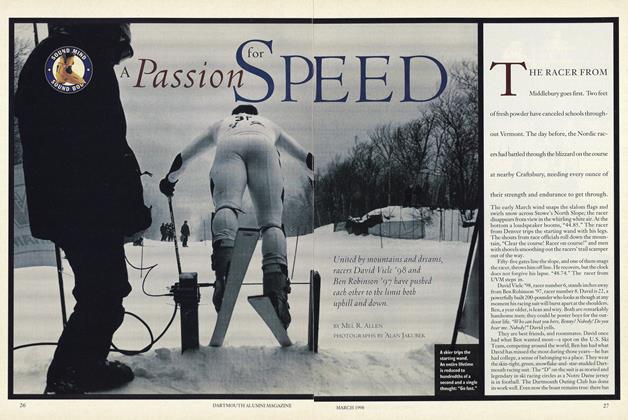

FeatureA Passion for Speed

March 1998 By Mel R. Allen -

Feature

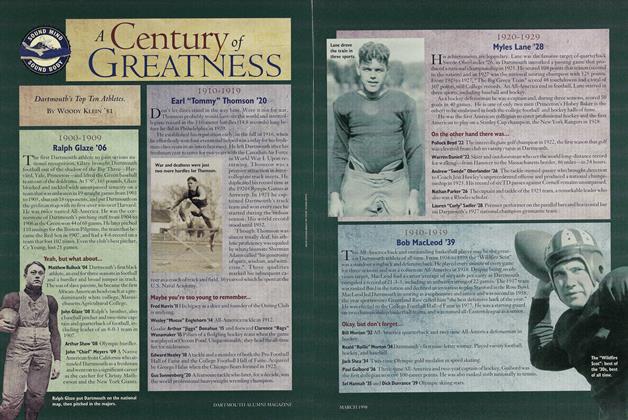

FeatureA Century of Greatness

March 1998 By Woody Klein '51 -

Cover Story

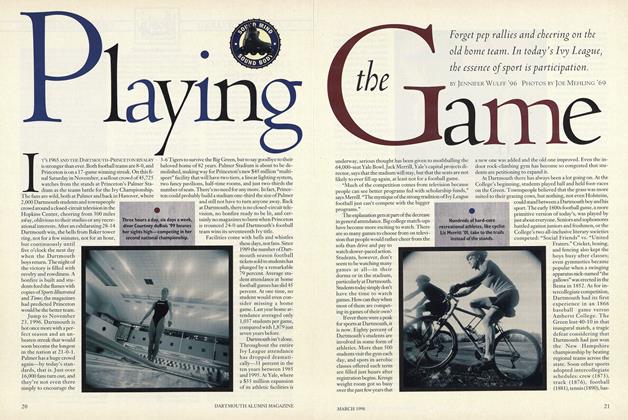

Cover StoryPlaying the Game

March 1998 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

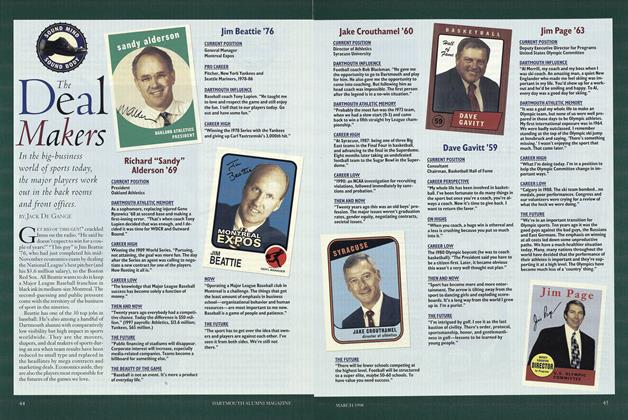

FeatureThe Deal Makers

March 1998 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

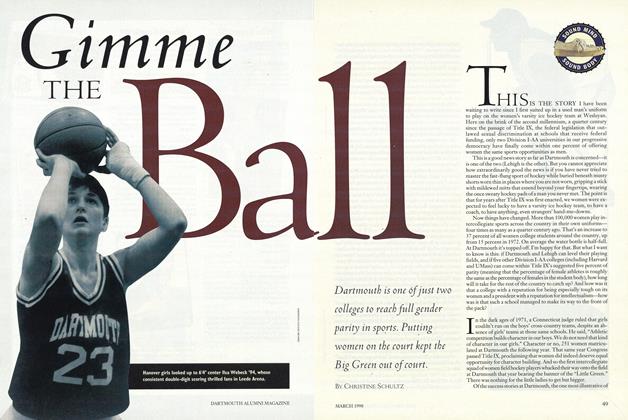

FeatureGimme the Ball

March 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleProf Note

December 1992 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Article

ArticleJoining the Queue

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Corset Controversy.

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleVirtual Munchausen

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHAT HAPPENED TO THE DEMOCRATS?

APRIL 1989 By Robert Arseneau, Karen Endicott