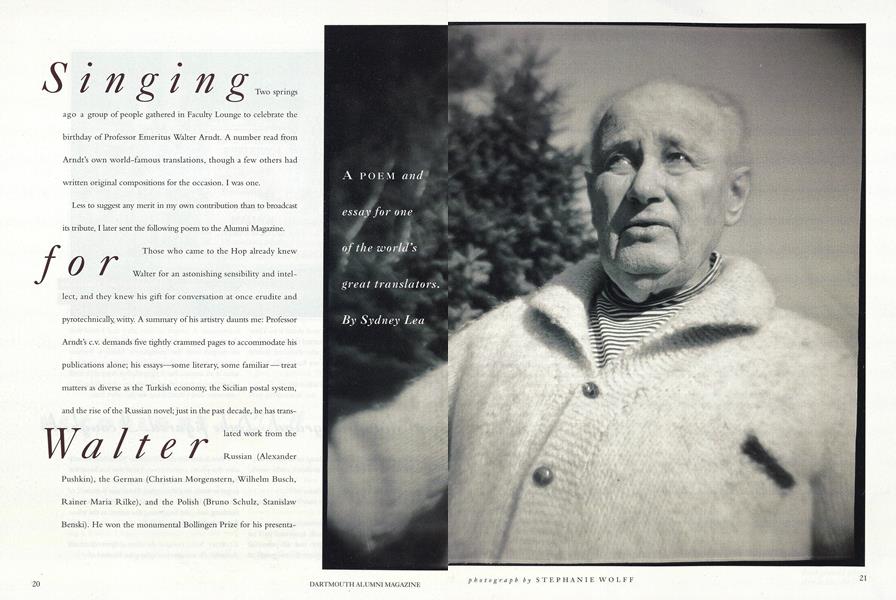

Two springs ago a group of people gathered in Faculty Lounge to celebrate the birthday of Professor Emeritus Walter Arndt. A number read from Arndt's own world-famous translations, though a few others had written original compositions for the occasion. I was one. Less to suggest any merit in my own contribution than to broadcast its tribute, I later sent the following poem to the Alumni Magazine.

Those who came to the Hop already knew Walter for an astonishing sensibility and intellect, and they knew his gift for conversation at once erudite and pyrotechnically witty. A summary of his artistry daunts me: Professor Arndt's c.v. demands five tightly crammed pages to accommodate his publications alone; his essays some literary, some familiar treat matters as diverse as the Turkish economy, the Sicilian postal system, and the rise of the Russian novel; just in the past decade, he has translated

work from the Russian (Alexander Pushkin), the German (Christian Morgenstern, Wilhelm Busch, Rainer Maria Rilke), and the Polish (Bruno Schulz, Stanislaw Benski). He won the monumental Bollingen Prize for his presentation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin.

But I believe his own greatest pride lies in form-true poetry translations. Discontent with, or, more accurately, infuriated by applications of "free" English prosody and measure to far stricter models, this writer brilliantly replicates not only every thematic property of his originals' verse but also every technical one.

Walter and Miriam Arndt arrived on this plain in 1966. She is a secondary school teacher and tutor, and until retirement her husband taught in Dartmouth's Russian Department, which he also periodically chaired. His career blends motifs from high comedy, suspense thriller, and military docudrama. Born in 1916 at Constantinople as a citizen of the "Free and Hanseatic City" of Hamburg, he was classically schooled in what was then Breslau. His father, a professor of chemistry, received a call to Oxford in 1933, and a year later the son followed. At Oriel College, the younger Arndt read economics and political science, then proceeded to Warsaw for graduate study in classics, linguistics, and Slavic languages and literatures, chiefly Russian. To prepare for prospective stewardship of family holdings in Polish industry, he took an M.A. in economics and business at the same time. (One soon begins to wonder if this man has ever pursued one aim at a time.)

over his German passport and volunteered for the Polish army. He was captured in 1939, but escaped from a makeshift POW camp and spent the succeeding year as a member of the Reacting to grim political developments in the Spain and Czechoslovakia of 1936, Arndt turned nascent Polish underground, primarily forging passes and permits from stolen Nazi documents. In late 1940, having himself laid hold of dubious Turkish papers, he made his way back to Constantinople, now Istanbul, where his father had become an advisor to Ataturk. Walter registered with the Polish forces in the Near and Middle East, but in a tenuous civilian interlude provided by the Turks' neutrality, our Wunderkind enrolled in the American School of Engineering at Robert College, meantime privately continuing his study of Russian.

In 1942, Arndt was transferred to the Turkish headquarters of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, which was much involved in persuading the Germans' Balkan satellites to surrender to the Allies before having to cede to the advancing Soviet armies, and which through the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee also received the first hard accounts of Nazi annihilation camps in Poland.

From 1945, Arndt both taught at Robert College and held posts in United Nations relief and resettlement agencies, until in 1949 he, Miriam, and their two sons emigrated to North Carolina, where two more children, both daughters, were born. He was a teacher (classics, Greek, Latin, French, German, Russian) at Guilford College, and also a graduate student (econoic theory, classics) and instructor (Russian language) at the University of North Carolina, which awarded him a Ph.D. in 1956. He held Ford fellowships at Michigan and Harvard, successive appointments in his fields at Chapel Hill, and guest professorships at Munster University and the University of Colorado before moving to Dartmouth College.

After this epical account, my few comments on "Spring Song for Walter Arndt at 75" must seem almost laughably pastoral. The poem took its origin from a passage in Arndt's textual translation of The Letters andDrawings of Bruno Schulz (Harper & Row, 1989). A portion of that passage is italicized in my piece opposite. In it I found an analogue to the spirit of Walter himself, whose metaphorical capaciousness and generosity seem akin to Jesus' stable as Schulz envisions it. (I hasten to add that for metrical reasons I substitute the word "akin" for the original "like." Who would notice? Walter would.) Thus, a Christian image as used by an urbane Jew made its way into a somewhat countrified Christian's poem: that very fact, like the image of the stable itself, again suggested the spiritual grandeur of Professor Arndt, able as he is to attract and reconcile such a polymorphous host of other spirits. From my own metaphorical woods I then fetched up a battered pine, which I greeted as "Jacob-called-Israel" in my daily hikes up Stonehouse Mountain, in Orford, New Hampshire, where I used to live. So the Gentile presents a Judaic figure, as it were tit for tat, the poem's aim being to convey the unifying energy that Walter Arndt brings to any gathering. But my efforts in "Spring Song..." are less eloquent on this score than the simultaneous diversity and congeniality of those who honored him in Faculty Lounge two years ago. I chose the couplet form by way of implying not only this "tightness" but also of imitating very imperfectly the care and deliberation of Arndt's work in verse. As for my literary allusions, the reader by now will sense the relevance of Schulz, Pushkin, and Rilke; but there is also a translator's pun on the name of another poet brought to prominence by Walter, Christian Morgenstern: "the morning star," a body as bright and rife with literary complexity as Professor Arndt himself.

A POEM andessay for oneof the world'sgreat translators.

Walter and Miriam, a teacher, immigrated in 1949.

His CAREER BLENDS MOTIFS from high comedy, suspensethriller, and military docudrama. After this epical account, myfew comments must seem almost laughably pastoral.

Spring Song for Walter Arndt at 75 Last night, from north, the wind that I name Angel Flew to a landmark pine I cherish. They grappled. Jacob-called-Israel, I dubbed that tree. Because, like you, I must joke as I must sneeze. Which is not to say, dear Seeks the trivial. Keen speech, crucial- Like the morning star, Rainer, heroic Pushkin; Like the figures and rhythms with which you lovingly dress them. All crucial, we hope, though all may weaken and die: My pine seemed almost an invalid there, on high, Its woodpecker-holes had the look of eyes in old albums. Your Bruno Schulz wrote that at length for unexplored reasonsHuman metaphors, projects, dreams beginTo hanker for realizatin. That's when the time Of autumn is at hand... Man's house becomesAkin to the little stable of Bethlehem, Around which all spirits, upper and lower, condense. Is it now the fall? To say so would make some sense. If in fact your wit had weakened, not to say broken. Yet you wrestle to speak, and therefore will always have spoken. I recall the hue of last November's woods. I see it again on the hills, in the Maytime buds. Breatliing color and life into word after winter-gray word. You realize so much of our hankering world. Someone or -thing has blessed you, blessing lis. You summon 'spirits' exalted and common close, Like Jacob-called-Israel, or that Bethlehem stable. Enough. These metaphors begin to jumble While yours, somehow inspired by every storm. Fly from your hand into cogent and lasting song. I think of my highcountry pine, still evergreen. How it proffers, aloft on a scarp, its bright new cones, How it serves at once as trope and tree and shelter, How well it translates the roistering woodpecker's laughter. Background photo:Arndt in 1943.

A nationally known poet and essayist, SYDNEY LEA taught at Dartmouthfrom 1970 to 1979. He is the authorof five volumes of poetry and a novel, A Place in Mind, and is finishing abook of memoiristic essays. Lea is afounder of the New England Review anda member of the MFA faculty atVermont College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFor The Sake Of Argument

February 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

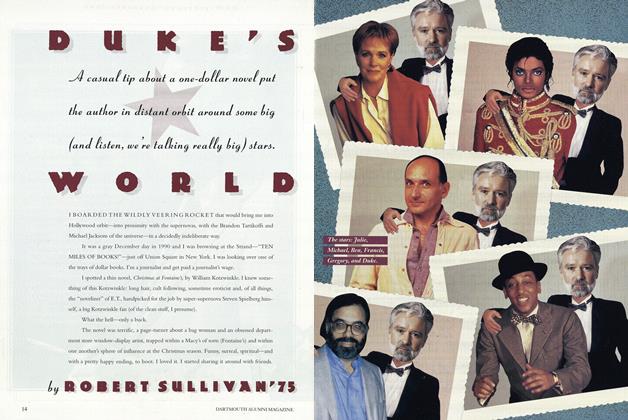

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleImagining the Orient

February 1993 By Douglas Haynes -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

February 1993 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Features

-

Feature

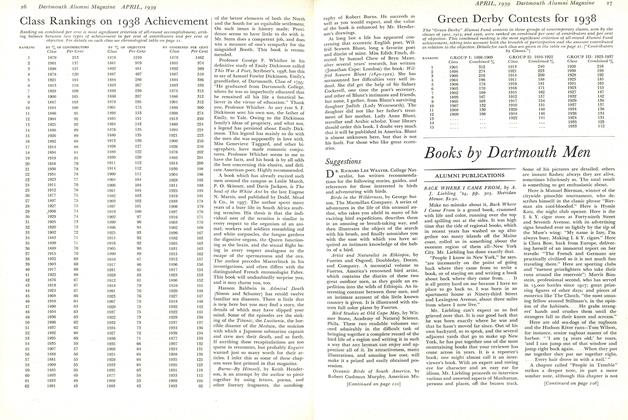

FeatureGlass Rankings on 1938 Achievement

April 1939 -

Feature

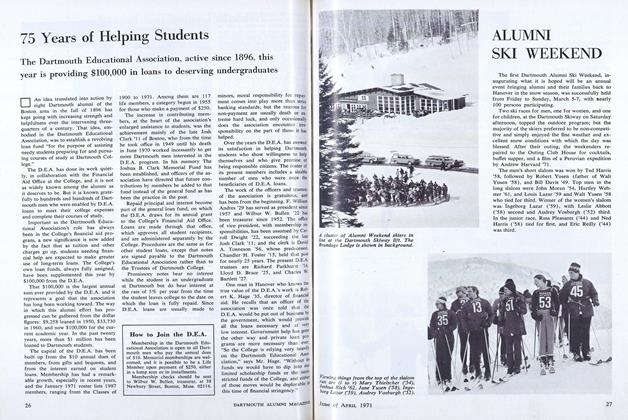

FeatureALUMNI SKI WEEKEND

APRIL 1971 -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

JUNE 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureScions of Rhodes

JAN./FEB. 1978 By Daniela Weiser-Varon -

Feature

FeatureA Tuckerman Tradition

April 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Cover Story

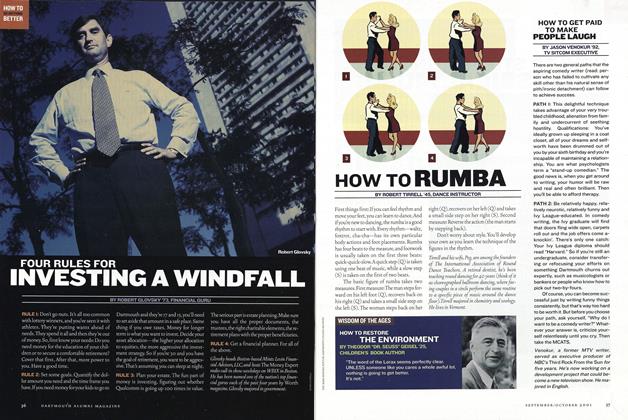

Cover StoryHOW TO RUMBA

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT TIRRELL '45