One morning six years ago my wife and children came back from a weekend away to find me with a two-day beard and surrounded by paper. I had eaten nothing more than a couple of bananas, and had slept just a few hours during the entire time. My weekend had been spent writing an essay for Dartmouth's Master of Arts & Liberal Studies program. "Dad," my daughter said when she saw me. "Why are you doing this?" Several days later, when the paper came back with an order by my professor to rewrite it, I began to ask myself the same question. Why on earth was I driving 120 miles three days a week for the opportunity to rewrite papers?

My return to the classroom as a graduate student had little to do with career advancement: I already had a doctorate and a secure college deanship. What I didn't have was intellectual excitement, a passionate involvement with learning. In fact, I felt a certain stagnation in my life. Over the years since college, I had slowly realized that my formal education had provided me with answers before I ever understood (or even asked) the questions. Mortimer Adler observes in Schooling is NotEnough that true learning and insight begin in one's 40s and 50s; sound judgment ment and practical wisdom develop only after one turns 60. If that is so, I was right on life's schedule. I took courses ranging from "The Roots of Individualism" and "Life at the Top: The Study of Flowering Plants and Human Development" to "Social Protest" and an independent study on "Group Defamation and Freedom of Speech." The course that most opened my eyes and ears was the last one I took, "Opera: A Synthesis of the Arts." I had never been to an opera had never thought of it. Yet Wagner sang to some part of me. Yearning for the ideal, agonized by the discrepancies between the real and the ideal, Wagner's heroes are transformed and made whole at last by the redemptive power of compassion. These themes, which Wagner tackled in both opera and life, became the essence of my thesis, "The Wagnerian Hero and the Quest for Self-knowledge." They also became vehicles for my own exploration.

My search will continue for what Wendell Berry calls the "profound communion" of one's inner life with the outer. I hope to return to Dartmouth and take more courses when I'm in my 60s. I do not know if I will be wise then, as Adler predicts. But I know I will be at least as open to the ideal of the liberal arts: to affirm the possibility of meaning and knowledge of a moral order.

William Laramee, dean ofinstitutional advancement atLyndon State College inLyndonville, Vermont, andpresident of the MALSAlumni Council, is one of the633 people who have earnedMALS degrees since the programbegan in 1970.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

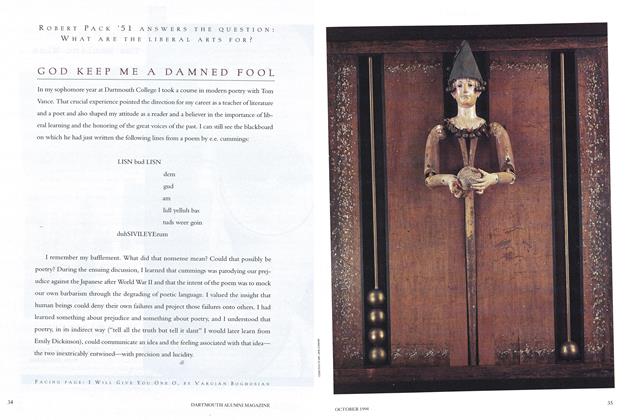

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

October 1994 By Varujan Boghosian -

Cover Story

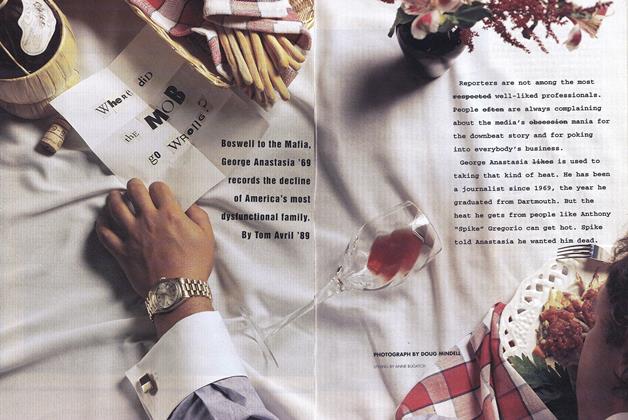

Cover StoryWhere did the Mob go Wrong?

October 1994 By Tom Avril '89 -

Feature

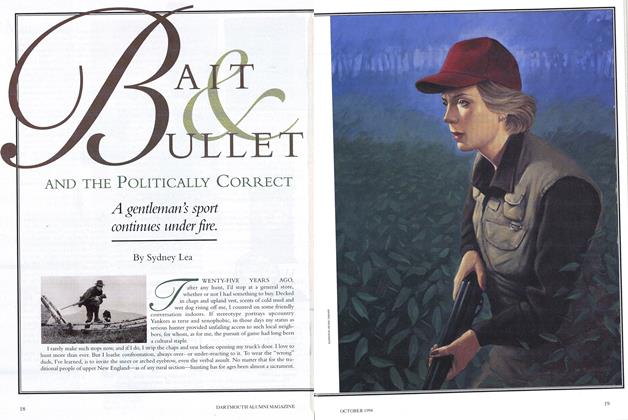

FeatureBait & Bullet and the Politically Correct

October 1994 By Sydney Lea -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Testa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

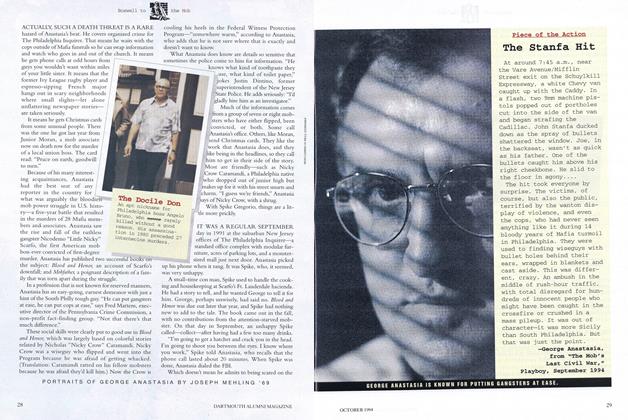

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

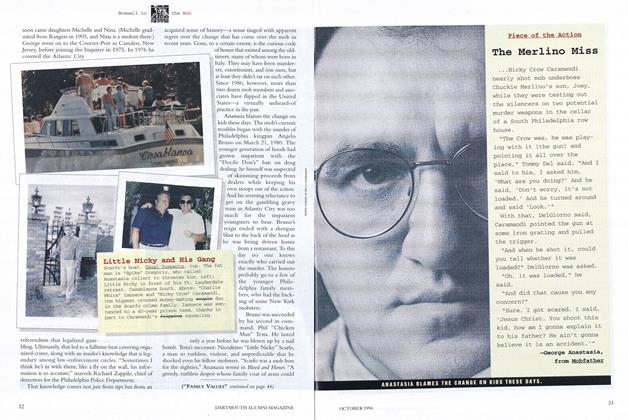

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Merlino Miss

October 1994 By George Anastasia

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident Announces Other Appointments

October 1948 -

Article

ArticleOnline catalog ushers in age of library automation

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

ArticleFace to Watch

May/June 2002 -

Article

ArticleBeyond Good Ground

May 1979 By GREGORY RABASSA '44 -

Article

ArticleLOOK WHO’S TALKING

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Lexi Krupp ’15 -

Article

ArticleOn June 23 choreographer Moses Pendleton '71

October 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96