DROP andGiveMeTwentyStop whimperingand take a lookinside Dartmouth 'sembattledmilitary corps.

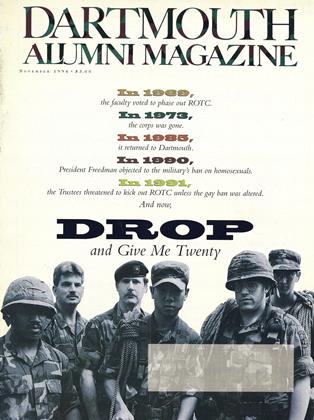

IT MAY HAVE BEEN the greatest survival test Dartmouth's Reserve Officer Training Corps had ever faced, and the program passed—at least for the moment. Last April the College's Board of Trustees backed off a three-year-old ultimatum over the military's policy on homosexuals.

This was not the first time ROTC had been given a lastminute reprieve. The Trustees had already extended the deadline once before, after President Bill Clinton promised to change the military policy that prohibited gays from serving. The compromise that resulted—"don't ask, don't tell, don't pursue"— was rejected as inadequate by gay activists, faculty members, and, finally, President James O. Freedman, who is a friend of Clinton's.

For Dartmouth, the issue was settled by a clearly anguished Board of Trustees, which acknowledged that the military policy still discriminated against homosexuals and thus violated the College's own non-discrimination policy. But the Trustees voted to keep the program anyway, citing in a brief statement the opportunity it offers to Dartmouth students and the Trustees' belief that society will one day accept homosexuals serving in the military.

For the cadets serving in Dartmouth's ROTC, the decision was a welcome relief from the constant spotlight shone on this tiny program at the outskirts of campus. But now that the program is entrenched, at least for the short term, it is useful to take a look at what it entails these days.

ROTC IS OF COURSE a military program, but its more specific purpose is to teach what the Pentagon likes to call leadership. When the 25 Dartmouth students currently enrolled in the program graduate, they will be commissioned in the army as second lieutenants. Most of the students will probably end up someplace other than a battlefield, serving the army in such peaceful ways as law, medicine, and engineering.

Terry Damm, a 42-year-old sergeant and former Green Beret who oversees the cadets at Dartmouth, explains that the training tries to bring out students' native ability to lead others. Everyone's gotleadership," hesays. "You put them in charge and show them how to perform your requirements. They go through the steps—understanding the mission, assigning the tasks, following up on the supervision plan.'' Students meet in the classroom once a week and then apply that lesson in a "lab" outside. They also spend three days a week in physical training.

In a class last July—a smaller group than the rest of the year because summer term is devoted nearly entirely to juniors Dammlecturedto his cadets on the elements ofleadership. "There's a lot to leading," he tells the seven students. It starts with receiving the mission and breaking it down to relevant information for subordinates, he says. "You've got to bring it down to where the little guys understand it. Don't give them a thesis.

"Don't just accept things—ask questions," Damm continues. But by this he clearly meant asking questions about the mission, not challenging the order. "Supervision is a key aspect of leadership. You can't just tell someone to do it," he says. "You supervise. You make it happen. And make sure I supervise the people underme."

These students will outrank Damm when they graduate in two years. On their jobs, they will be twenty-something commissioned officers overseeing 40-year-old military careerists. But they had better not cop an attitude, Damm warns them. "How many of you think you can go in and tell a sergeant-major what to do? Because if you do, I'll throw you outright now. You outrank him, but he knows people above you."

The students nod in agreement.

"You guys, in three or four years, will be making more money than I do now," he adds. "That's OK. You have a lot more responsibility. If you tell me to do something and it fails, it's your fault, not mine."

Damm supplements each classroom session with a talk on current events. "What's new in the world?" he asks.

"Kim-I1 Sung is dead," says one student.

Another asks Damm if he is happy about it.

"I think it's appropriate," Damm answers. Most dictators don't leave with a lot of sympathy."

The sergeant also informs the students that the army is considering relaxing its restrictions on overweight people." As it stands now, the army can throw you out because you don't have the right image—a pot belly," Damm says.

Two days later, six of the students—five men and one woman—carry out a mission. They leave the classroom in Leverone Field House, cross North Park Street, and go down to the bank of a dried-up creek behind Chase Field.

The students find the mission requires more than leadership skills; it also demands a little imagination. "This is a raging stream," Damm asserts, pointing to the dry creek. He tells the students to clear the area so they can lay out a rope. As a student starts to pull out some weeds, Damm quips: "Don't get us in environmental trouble."

Damm instructs the students on how to tie a rope around their bodies. Christian Schrobsdorff'96 does it a different way.

"Do it my way," Damm instructs him.

"My way is much faster," says Schrobsdorff, a 25-year-old student who served four years in the navy after graduating from high school.

"Just do it my way, so I know you can do it,'' answers Damm.

The plan is to build a rope bridge across the stream. But that requires one cadet to wade across the stream, with a rope tied across his waist in case he needs to be pulled back. If there were real water, he would be naked," carrying only his weapon, says Damm. "There's no reason for him to get his clothes wet."

When the student gets across, he ties one end of the rope around a tree. The remaining students tie the other end around a tree on their side, forming a taut 50- foot-long rope bridge. They then tie individual ropes around their waists and between their legs.

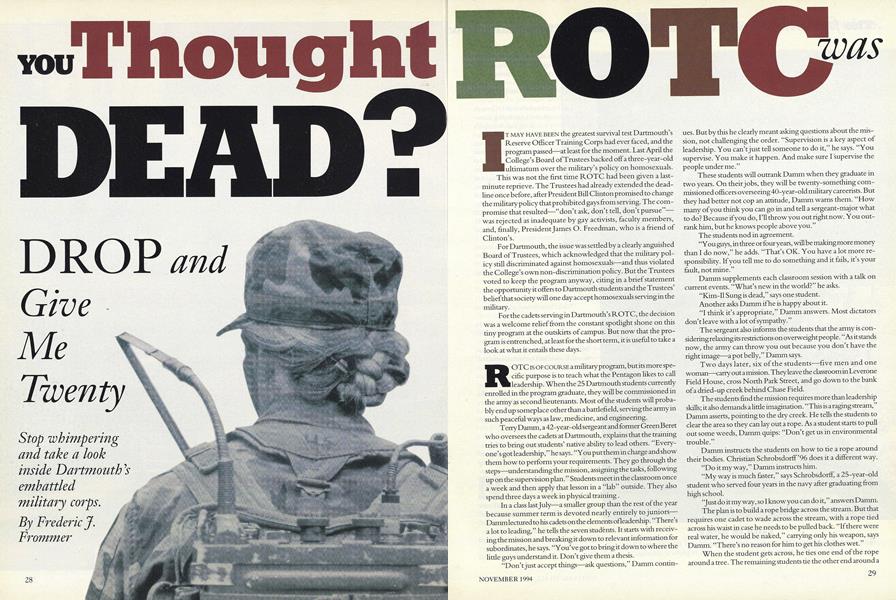

"This is sexy," notes cadet Brandon del Pozo '96.

Latching themselves onto the rope with carabiners, the students drag themselves one by one along the underbelly of the rope bridge. Del Pozo is the first across. He must carry not only his own backpack but the pack of the student who waded across the stream. He does this by towing the second backpack, which is attached to a second loop and connected to his body by a second rope.

It does not look easy. Dragged down by his own weight and that of the 40-pound packs, he drags across the ground before reaching the stream. He becomes airborne but fails to get all the way across in one try.

Damm gives the students a lesson in survival of the fittest, as it applies to the army. "You send over the least valuable guy across the river to swim—the guy you're willing to sacrifice."

"You mean the guy nobody likes?" asks delPozo.

"I didn't say the least popular, "says Damm.

After Damm, a solidly built 22 year army careerist, demonstrates how to cross the bridge, Carrington Bradley '96 goes across the rope on the opposite side from what Damm has instructed. Damm yells after him as Bradley rattles across the rope with a great deal of friction and noise. Bradley, still on the rope, says he thought Damm had chosen the wrong side. "You were right," Bradley admits now.

"Thankyou," says Damm wryly. "I try."

IN AN INTERVIEW later, Bradley explains that he was simply being curious; he was not trying to showup Damm. "He knows-a hell ofalotmore of this stuff than we do," says Bradley. "He's seen a lot of things, done a lot of things. I have a great deal of respect for him. When I outrank him—you know in your mind he knows more than you."

Perhaps as a gentle punishment, Damm assigns Bradley to play an injured soldier who needs to be carried across the stream. Tied up on an elastic stretcher like a mummy, he is attached to the rope bridge by a metal loop and towed across by another student. For the first few feet, before getting over the creek, Bradley's body drags along the ground. "Of course, if I had a spinal injury, I'd be dead," he says matter-of-factly.

"Oh, be quiet," says Damm, in a far calmer voice than that of the traditional sergeant of old. "Stop whimpering! You're lucky to be alive." Damm hustles over to his camera and snaps some Polaroids.

The friendly banter between student and teacher shows this is much more relaxed than active service. And Damm, who has been running the Dartmouth program for a little over a year, wants it that way. "I realize these guys are students, " he says. "They come here, and for a while they change gears. The military is more strict. I can't treat them in the same way as people who have been in the military for years."

Bradley says the program rarely interferes with school, since ROTC class is scheduled around other classes. "Sgt. Damm is very flexible. He realizes that ROTC is a lower priority."

But Bradley complains about a book report that Damm has assigned the students. "At the end of the term, I won't have time to do it," he says. "I'll end up doing it, but it won't be top quality. That borders on being intrusive."

There is a serious time commitment, but ROTC—which doesn't earn the students any academic credit— is almost like an extracurricular activity. "I enjoy practicing my marksmanship," says Bradley, "and practicing raids and ambushes. They are like games—cowboys and Indians for adults."

Del Pozo sees it the same way. "It appeals to the kid in you," he says. "Like cowboys and Indians. It's like playing war. And it is helping to get him in shape, he adds.

NO OTHER EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITY pays as well. ROTC scholarships provide students with 80 percent of their tuition, $l00 monthly stipends, and $450 for books, regardless of need. In exchange, students must serve as officers in the military for eight years. Much of that service can be done through the reserves.

After Dartmouth's faculty voted to expel ROTC last winter, College officials said that about half of the students would qual- ify for financial aid, at a cost to the school of between $60,000 and $80,000. But much of that aid would come in the form of loans, which would be an inadequate alternative for students who already expect to be saddled with debt from graduate school. According to Damm, ROTC generates more than $250,000 a year for tuition.

Pace Duckenfield '96 says he would never have attended Dartmouth if not for the ROTC scholarship. "I want to go to grad school after this, and I'm going to pay for that primarily by myself, " he says. "It's better that I come out ofhere with as little debt as possible." Duckenfield plans on going to law school and serving in the Judge Advocate General Corps.

Students say there are other benefits besides financial ones. "It's a good character-builder," says Christian Schrobsdorff, a 25 year-old junior from Warren, Massachusetts. It does a good job of teaching students to work together as a team. Most regular classes are cutthroat." Schrobsdorff, whose navy record allows him to be one the few ROTC students not on scholarship, plans on going to law school after he graduates.

A few cadets complain that others are in it only tor the money. "It sort of annoys me that some people are less motivated than others, " says Bradley, who admits he "originally signed up for the wrong reason"—money. "They don't come to class, they sort of slack off, not really caring about their appearance." Bradley, who is from Richmond, Virginia, says he will serve in an army engineering unit after graduation.

"I look with disdain upon people who look for this for a free ride" and then get upset when they are called up, agrees del Pozo. "This is for a real purpose." The Brooklyn native says he has always liked the military. His father served as a medic during the Vietnam War, and his grandfather was aparatrooper during World War 11. "I thought I wouldn't be happy unless I spent a few years doing this," he says, recalling that the males in his family supported his decision while the women discouraged him. He plans on joining the infantry and then becoming a writer, possibly a journalist. He had an op-ed piece published in The New York Times a few days before the trustee vote on ROTC, arguing that college-educated cadets will actually make the military more tolerant of gays.

Such students eventually form the backbone of the officer corps, according to Major Robert Shepherd, a public affairs officer with the national Army ROTC program. He says the training program generates 70 percent of the army's commissioned officers. "Historically, what the army values is the diversity that they represent," he says. "That young man or woman is a product of that college, and brings the training they learned at that collegeeducation, discipline."

THE COLLEGE HAS NOT always been unanimously enthusiastic about providing that product. Dartmouth and ROTC have had a long and sometimes rocky relationship that predates the flap over homosexual policy. Originally established as a navy program during World War 11, ROTC had air force and army units established during the Korean War. The low point for the program was in the seventies. In response to the Vietnam War, the faculty voted in 1969 to phase out ROTC, and the Trustees agreed. The corps was gone by 1973.

It returnedin 1985. In a pattern that would repeat itself a decade later, the Trustees and students supported bringing it back over the overwhelming opposition of the faculty, which had voted nearly three to one for a ban. In 1990 President Freedman wrote to then Defense Secretary Richard Cheney, saying that the military's ban on homosexuals was discriminatory and that it created' 'serious administrative and moral problems" on college campuses. That was followed a year later by the Trustees' ultimatum that they would discontinue Dartmouth's affiliation with ROTC unless the policy was altered. Over the next three years, however, the Trustees' membership had changed significantly. Chairman Ira Michael Hey man '51, who had been a forceful advocate of the ultimatum, retired. It was this new board that backed off the ultimatum last spring.

The reaction in the gay community was predictably strong. Drama professor jim StefFensen said he served in ROTC when he was in college, and that a gay contemporary of his was killed in the Korean War. "He was killed for values that the military and the Trustees can't support," StefFensen said after the vote. The policy is a desecration ofhis memory," Another professor said the Trustees were wrong to see the issue in terms of shaping national policy; the issue was discrimination on the campus. "I have never tried to use Dartmouth as a national weapon," said English professor Peter Saccio, his voice rising. "I care about Dartmouth. They should too."

Not all opponents of ROT C think that gay rights is the sole issue. Some simply don't like the military. "In the United States today, militarism is a problem," math professorj ohn Lamperti said at the faculty meeting to debate ROTC. He argued that elimi- nating the program "would be a form of public service."

Del Pozo calls such an argument "single-minded." "The fact that we go to a liberal arts college ingrains in us that we have to temper our military views," he says. "You need people to think, and to realize that most of the time you shouldn't fight."

Still, the debate over homosexuality is the crux of the matter. The new policy prohibits military officials from asking people if they are gay, but it also prohibits men and women from engaging in homosexual conduct—on or off base. Most ROTC students acknowledge that the policy is still discriminatory, but they say the only way to make the military more tolerant is to get people like themin leadership positions. "Keeping the ROTC programis better as a whole to bringing a progressive nature into the military," says Bjorn Kilburn, a senior. "While ROTC may compromise Dartmouth policy, it has a greater benefit for society."

Sgt. Damm himself remains philosophical about the criticism. "The policy hasn't changed as much as most people think," he says. "And that's upset a lot of people."

"This is sexy."Brandon del Pozo '96 rappels under the supervision of First Sergeant TerryDamm. The cadets spend three days a week in physical training.

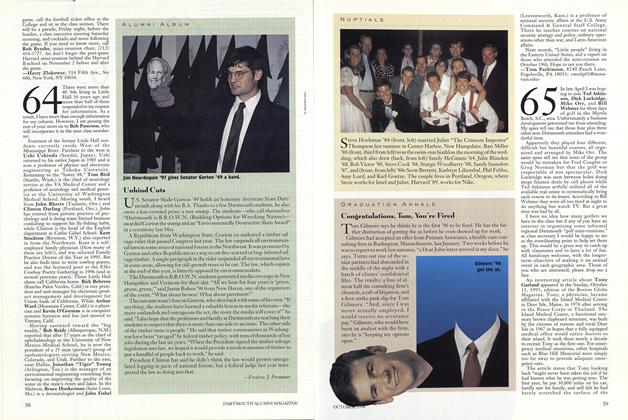

"Don't just accept things—ask questions,"Cadet Bjorn Kilburn '95 does a little leader training with his squad."Everyone's got leadership," says Sergeant Damm.

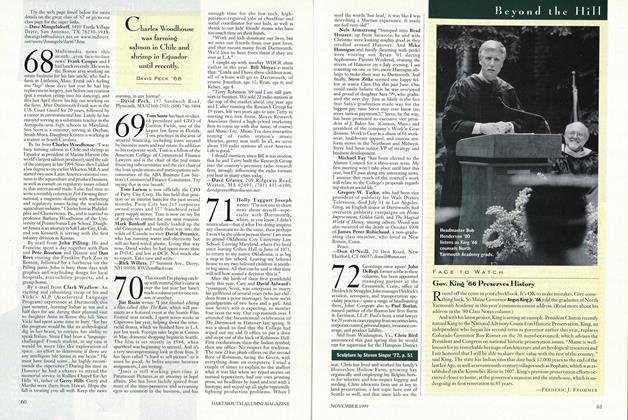

"Like cowboys and Indians."The Pentagon budget being what it is, sticks serve as automatic weapons—and pine conesas grenades—in the field. Most cadets will go on to non-combat duty.

friendly between student and TEACHER showsthis is much more RELAXED than ACTIVE service.

FREDERIC FROMMER is a reporter for the Valley News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLessons of a Legacy

November 1994 By Peter Blodgett '74 -

Cover Story

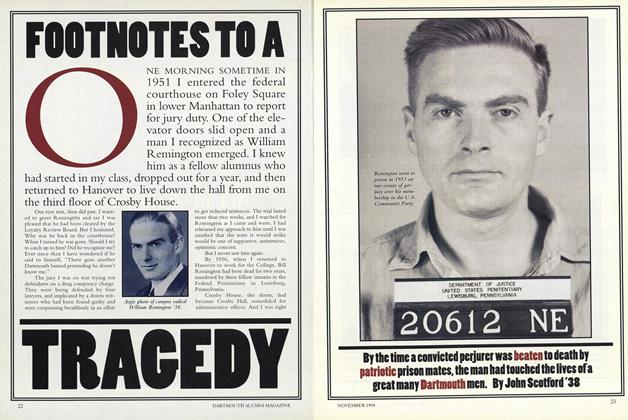

Cover StoryFOOTNOTES TO A TRAGEDY

November 1994 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

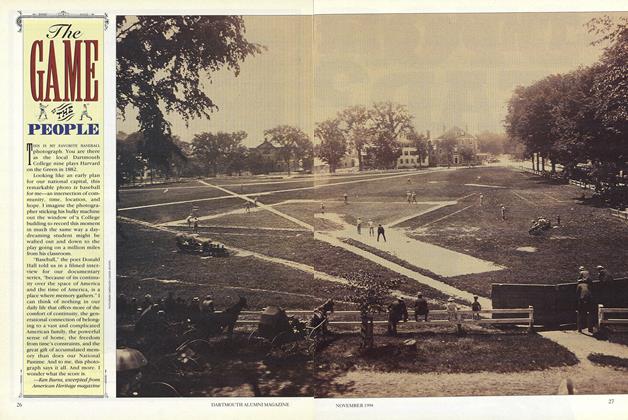

FeatureTHE GAME PEOPLE

November 1994 By Ken Burns -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

November 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

Frederic J. Frommer

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1960 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10 -

Feature

FeatureHamming It Up

NOVEMBER 1984 By Gay E. Milius, Jr. '33 and Dick Dorrance '36 -

Feature

FeatureOh, You Shouldn't Have!

MAY 1992 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60