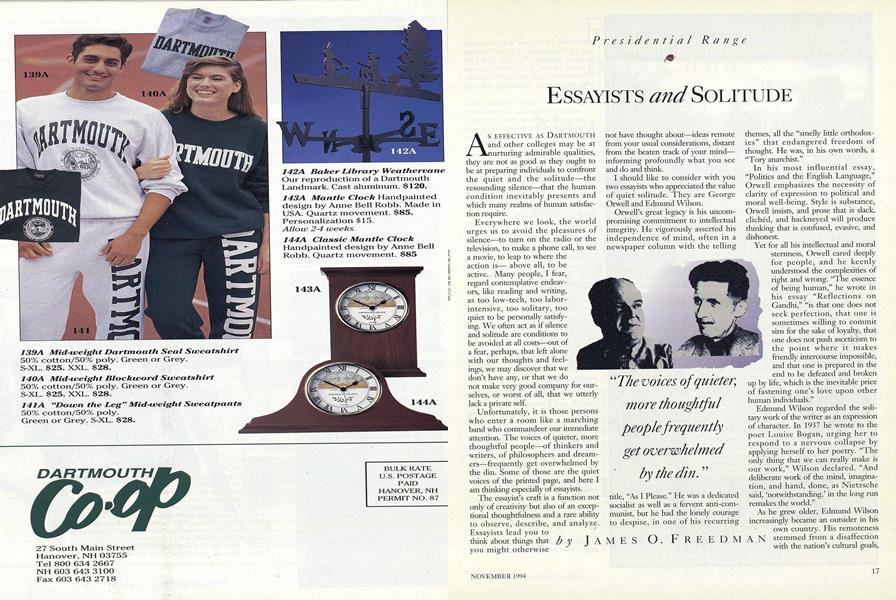

AS EFFECTIVE AS DARTMOUTH and other colleges may be at nurturing admirable qualities, they are not as good as they ought to be at preparing individuals to confront the quiet and the solitude—the resounding silence—that the human condition inevitably presents and which many realms of human satisfaction require.

Everywhere we look, the world urges us to avoid the pleasures of silence—to turn on the radio or the television, to make a phone call, to see a movie, to leap to where the action is— above all, to be active. Many people, I fear, regard contemplative endeavors, like reading and writing, as too low-tech, too laborintensive, too solitary, too quiet to be personally satisfying. We often act as if silence and solitude are conditions to be avoided at all costs—out of a fear, perhaps, that left alone with our thoughts and feelings, we may discover that we don't have any, or that we do not make very good company for ourselves, or worst of all, that we utterly lack a private self.

Unfortunately, it is those persons who enter a room like a marching band who commandeer our immediate attention. The voices of quieter, more thoughtful people—of thinkers and writers, of philosophers and dreamers—frequently get overwhelmed by the din. Some of those are the quiet voices of the printed page, and here I am thinking especially of essayists.

The essayist's craft is a function not only of creativity but also of an exceptional thoughtfulness and a rare ability to observe, describe, and analyze. Essayists lead you to think about things that you might otherwise not have thought about—ideas remote from your usual considerations, distant from the beaten track of your mindinforming profoundly what you see and do and think.

I should like to consider with you two essayists who appreciated the value of quiet solitude. They are George Orwell and Edmund Wilson.

Orwell's great legacy is his uncompromising commitment to intellectual integrity. He vigorously asserted his independence of mind, often in a newspaper column with the telling title, "As I Please." He was a dedicated socialist as well as a fervent anti-communist, but he had the lonely courage to despise, in one of his recurring themes, all the "smelly little orthodoxies" that endangered freedom of thought. He was, in his own words, a "Tory anarchist."

In his most influential essay, "Politics and the English Language," Orwell emphasizes the necessity of clarity of expression to political and moral well-being. Style is substance, Orwell insists, and prose that is slack, cliched, and hackneyed will produce thinking that is confused, evasive, and dishonest.

Yet for all his intellectual and moral sternness, Orwell cared deeply for people, and he keenly understood the complexities of right and wrong. "The essence of being human," he wrote in his essay "Reflections on Gandhi," "is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes friendly intercourse impossible, and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one's love upon other human individuals."

Edmund Wilson regarded the soli- tary work of the writer as an expression of character. In 1937 he wrote to the poet Louise Bogan, urging her to respond to a nervous collapse by applying herself to her poetry. "The only thing that we can really make is our work," Wilson declared. "And deliberate work of the mind, imagination, and hand, done, as Nietzsche said, 'notwithstanding,' in the long run remakes the world."

As he grew older, Edmund Wilson increasingly became an outsider in his own country. His remoteness stemmed from a disaffection with the nation's cultural goals, particularly its rampant acquisitiveness, and an abhorrence of a proliferating defense budget. For ten years he refused to pay his income tax—a Thoreauvian tactic that cost him dearly in his ultimate accounting with the government.

However, if Wilson's distance from the center of American life reinforced a certain crabbedness in his temperament, causing some to fear that he was lapsing into the misanthropy of an H.L. Mencken, it also enabled him in his later years to see and report upon the nation's social and political life with a wry astringency. Thus, he wrote: "Robert Lowell has done something very extraordinary; he has made poetry out of modern Boston."

As the range of his books indicates—he also wrote on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Canadian and Russian literature, and Native American culture, as well as published novels and playsWilson was a true man of letters. His incisive mind and aggressive curiosity, his intellectual energy and imagination, his courage to be idiosyncratic, his interest in language and character, and his resistance to popular fads enabled him to continue to learn throughout his life and to say so much of import until its very end.

In 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Wilson the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The citation read: "Critic and historian, he has converted criticism itself into a creative act, while setting for the Nation a stern and uncompromising standard of independent judgment."

It is no coincidence that George Orwell and Edmund Wilson were each models of an uncompromising commitment to excellence, to intellectual integrity, and to political independence. Each was simultaneously engaged with his material and removed from it. In making unflinchingly honest appraisals of his subjects, each let sympathy and judgment fall where they might, pursuing truth to conclusions that often were unconventional or politically incorrect. Each possessed the kind of intellectual integrity and strength of character that is fortified by reflective solitude.

"The voices of quieter,more thoughtfulpeople frequentlyget overwhelmedby the din."

This essay was adapted from the president's 1994 Commencement address.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Feature

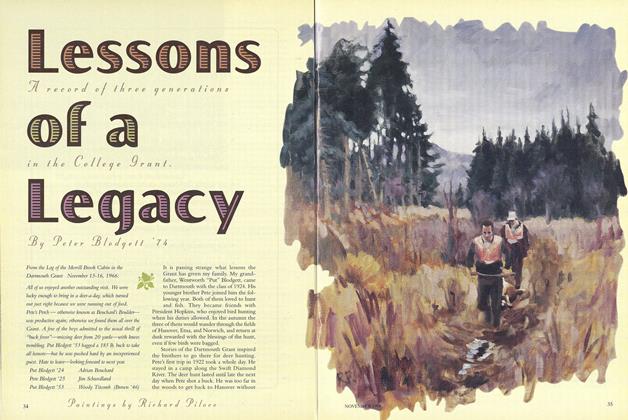

FeatureLessons of a Legacy

November 1994 By Peter Blodgett '74 -

Cover Story

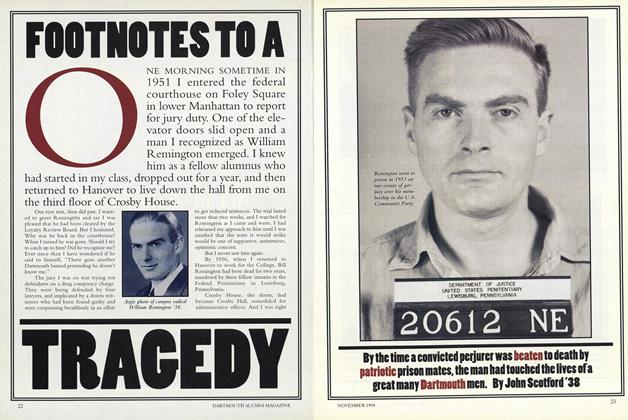

Cover StoryFOOTNOTES TO A TRAGEDY

November 1994 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

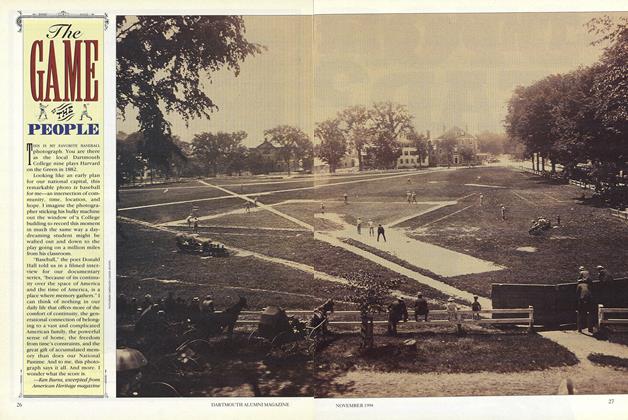

FeatureTHE GAME PEOPLE

November 1994 By Ken Burns -

Class Notes

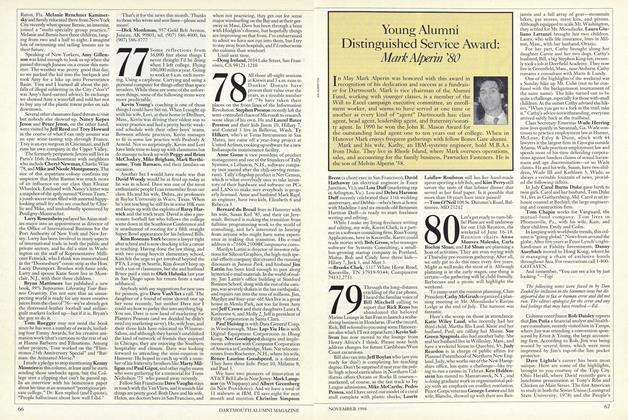

Class Notes1980

November 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleThe Freedom That Binds

MAY 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Wisdom For Peace

March 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Liberating Arts

MAY 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Quiet Greatness

DECEMBER 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLiving Well by Doing Good

NOVEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY NOTES

December, 1915 -

Article

ArticleStructured Freshman Year

MAY 1970 -

Article

ArticleDodds and Hill Elected Charter Trustees

MAY 1973 -

Article

ArticleA New Hurdle

MARCH 1931 By Harry Hillman -

Article

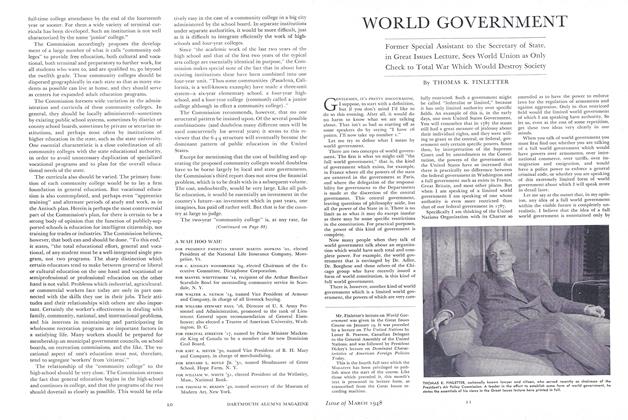

ArticleWORLD GOVERNMENT

March 1948 By THOMAS K. FIN LETTER -

Article

ArticleAbout 25 Years Ago

June 1937 By Warde Wilkins '13