Faculty dean and temporarypresident James Wright talks aboutDartmouth's competitive world.

As a Historian, I have learned that small decisions have unforeseen effects and cumulative influence; call it the principle of unintended consequence. One decision has had an impact on this College far greater than anyone might have intended, understood, or even necessarily wanted. That was the agreement that a group of eight northeastern private college and university presidents made in 1954 to establish the Ivy League. It had tremendous unintended consequences, perhaps more so for Dartmouth than for any of the other participating schools.

Basically the Ivy League was and indeed remains an athletic conference. The shared commitment that bound this group was to athletic scheduling, recruitment of student athletes, and financial aid. Indeed, athletics remain the binding theme and the major agenda when Ivy presidents gather.

In 1954 Dartmouth was something ofan anomaly in this group. The College was competitive with the other seven schools in athletics, but we were smaller in scale, we lacked substantial graduate programs, and our three professional schools were small. Back then Dartmouth might as naturally have joined an association with institutions such as Amherst, Williams, Middlebury, and other distinguished New England liberal-arts colleges. In fact, down through the thirties we had been competing athletically with these schools, the socalled Pentagonal Group, more than with those institutions that would become the Ivy League.

With the 1954 agreement Dartmouth castits lot with a different group. "Ivy League" has come to have a meaning and connotation that goes far beyond athletics. We continue to compete well in this athletic association; but now, in 1994, we also compete with Ivy schools to recruit faculty and students, for grants and for gifts, and for academic recognition.

And we compete because we must. Surely no responsible person speaking on behalf of this institution would suggest that Dartmouth is going to compete on the playing field or the ball court but not in the classroom or the laboratory. If these broader consequences were unintended, they were not necessarily unwanted. In all events, Ivy League membership provides for us a context, a range of aspirations, and a set of evaluative criteria that have imposed new expectations for Dartmouth.

It is easier, to be sure, to assess our athletic prowess than our academic standing. By most academic criteria I think we do well. The annual evaluation ofundergraduate programs by U.S. News & World Report has placed us from sixth to eighth in the category of "national universities," and a consistent fourth among the eight Ivy institutions. We are reg ularly ranked at or near the very top in student satisfaction, and a University of Pennsylvania study lastyear indicated that we were number one in the Ivy League in availability of faculty and in students' satisfaction with their choice of schools.

It is important to note the schools who are ahead of us in the U.S. News & World Report ranking: Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, Caltech,MlT, and now Duke. Caltech and MIT are in a category of their own, distinct and world-class. Among the other five schools that rank ahead of us, we are smaller and have far less in endowment and trust support per student.

As this comparison indicates, Dartmouth has a remarkable record of efficiency, of doing more with less. Over the last 20 years we expanded the student body without a commensurate expansion in academic facilities or in the tenure-track faculty. We operate on a year-round calendar; we run some 40 off-campus programs the sun never sets on Dartmouth College; we have developed new and expanded honors and research programs for individual students. There are many schools in the Ivy League and else where that would like to do these things as well a s we do them.

Over the past several years we have been particularly successful in recruiting faculty, often appointing the first-choice candidate. The number and the quality of student applicants have also been on the rise. And the new degree requirements, which take effect with the class of 1998, represent an important statement about the commitment of the Dartmouth faculty to look for new and different ways to improve what is an already sound academic program.

But of course these accomplishments are not the whole story. My Pollyanna inevitably has a Cassandra looking over her shoulder. We need to face up to problems of understanding, preserving, and enhancing our niche.

Why "preserve" as well as "enhance"? Here is Dartmouth's chief dilemma. Much of our strength comes from the quality of our undergraduate academic programs. They attract excellent faculty as well as students. Any growth, change, or expansion that does not preserve this essential core will not enhance us. Yet we cannot stand pat and simply preserve our undergraduate strength not without changing our competitive niche. Standing still is not an option.

First among our problems is the need to compensate faculty at a competitive level. Our salaries lag behind our comparison group.

A second concern is facilities. As we look to expand the faculty over the next fewyears, we also need to acknowledge that in many departments we have no space for the additions. Some spaces that we now use are not appropriate for the use of a research faculty, and our classrooms do not meet all of our needs. My own hope is to find ways for us to build new facilities for mathematics as well as psychology so that Bradley and Gerry Halls can be removed from the campus. A psychology building will open up some additional and significant space in Silsby Hall. Beyond these two new buildings, we should think about building a facility north of the Library that would be dedicated to classrooms and some teaching laboratories. This would permit us to better maintain and oversee the equipment and support of these classrooms. It would also permit us to convert some classrooms in existing buildings to offices or research laboratories.

Dollars and space. We never have enough of either. Yet more of each would no t be sufficient to preserve and enhance our niche. I have on numerous occasions stressed the need for a professional faculty that is also a teaching faculty. We attract exceptional undergraduate students. We need to make certain that in their studies they continue to encounter faculty who are engaged in the great work of their field and who also seek to share with their students the great joy of learning.

Related to this, and a matter that sharpens each of the issues that Dartmouth faces, is the complexity of sustaining modern science research and teaching programs at an Ivy League level. I hail from the end of campus where a small investment can enable a solitary scholar to conduct a significant amount of research. Modern science, in contrast, is collaborative and costly. Renovating, furnishing, and equipping a laboratory for a young scientist can cost $100,000 to $400,000. We could electnotto pay this. And we would fail to recruit our choices. And we would slip competitively and educationally. Even now our recruitment success in the sciences is not as high as in the social sciences and humanities.

The challenge is to improve our record in the sciences without sacrificing programs in the humanities and social sciences. Crowded introductory language courses and upperlevel social science courses must also be priority concerns. These needs, like recruitment costs, are not simply expenses; they are essential investments in our future.

Afewyears ago a colleague from the Economics

Department suggested that money is the report card of life. I have learned over the last several years not to debate market models with economists; but I would happily argue with them over report cards. I disagree with my friend's assertion. The monetary price of something has less to do with its intrinsic worth than with scarcity, production costs, and market factors. Budgets reflect costs, not value. Report cards, on the other hand, have to do with quality and accomplishment. If a mass spectrometer for an earth scientist costs $250,000 and a research trip for a historian to the British Museum costs $2,500, it surely does not mean that the research of one is 100 times more valuable to the institution than the other. The work of the physical scientist and that of the historian are equally important and equally valuable. The approach of the Dartmouth administration has been to provide whatever support we can to enable every faculty member to contribute fully to our common mission and our institutional purpose.

In tight times we must not simply make the penny-wise decisions about what we can afford to do. We also face those things that we can't afford not to do. I believe that Dartmouth cannot afford to walk away from competition in any of our academic areas. This does not mean that departments and individual faculty do not face some very tough choices. We cannotprovide comprehensive, across-the-board programs in all of our departments. We cannot do and be all things.

Oftentimes this debate about priorities has focused on the issue of graduate studies at Dartmouth. The historian in me couldn't resist reviewing the archives of the early sixties, when the Dartmouth faculty was debating the creation of modern Ph.D. programs. In 1966 the F acuity of Arts and Sciences voted to increase graduate enrollment to ten percent of undergraduate enrollment. The expectation in 1966 was that this level would be reached sometime in the middle seventies. In actuality, we have never reached this level. About one-half of graduate enrollment was to have been in the social sciences and humanities, with the other half in the natural sciences. Yet, with the exception of psychology, we have not added any doctoral programs in the humanities or social sciences. Nor am I aware of any current discussions thatwould propose any.

Nonetheless, I must ask the question: How long can Dartmouth afford to be a university pretending to be a college? An equally vexing, and perhaps more critical, question is: Howlong can Dartmouth be a college pretending to be a university? Unrealistic aspirations may be more troublesome than an tinwillingness to acknowledge change.

On second thought, I might change the verb "pretend," for I do not believe that there is any pretense involved in what is a genuine institutional ambivalence about our role and our goals. Efforts to resolve the ambivalence generally result in cathartic generalizations in which we insist that we combine many of the best elements of colleges and of universities. In fact I do not think this proposition is far from the truth. But maintaining our special niche is a complicated thing and likely will remain so. I do not believe that our aspirations are unrealistic; they are costly, in terms of our energies as well as our resources.

We have reason to be optimistic about our asks. For we work from a position of real strength.

Your's Read the Article: Now Turn the page... ..And Take Tour of the New Curriculum!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

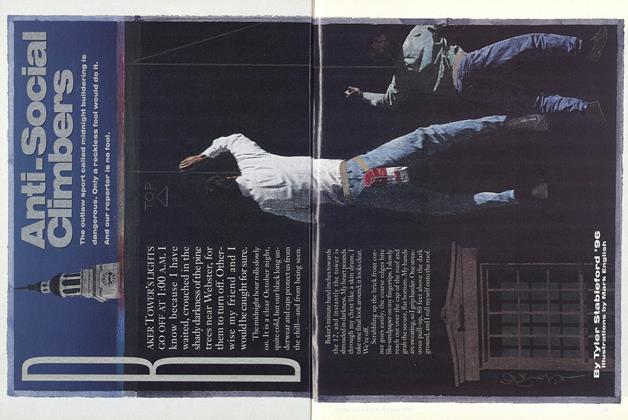

FeatureAnti-Social Climbers

December 1994 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1994 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleTied Up with Strings

December 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Overarching Concern

December 1994 By JAMES O. FREED MAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

December 1994 By Richard F. Perkins

Features

-

Feature

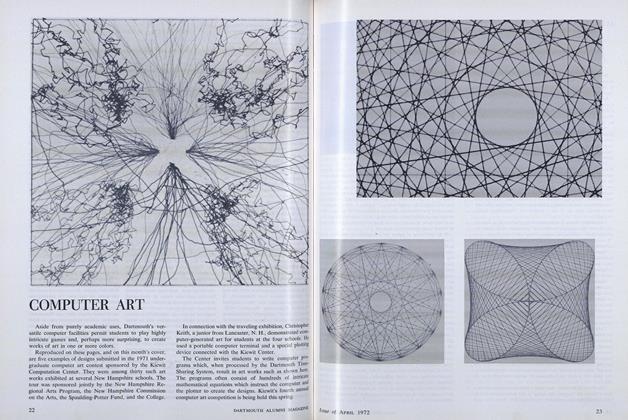

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

APRIL 1972 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Reynolds Professor of Geology 12 mountains in a single grant

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureEqual Opportunity

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureAn Uulikely Medical School

DECEMBER 1997 -

Feature

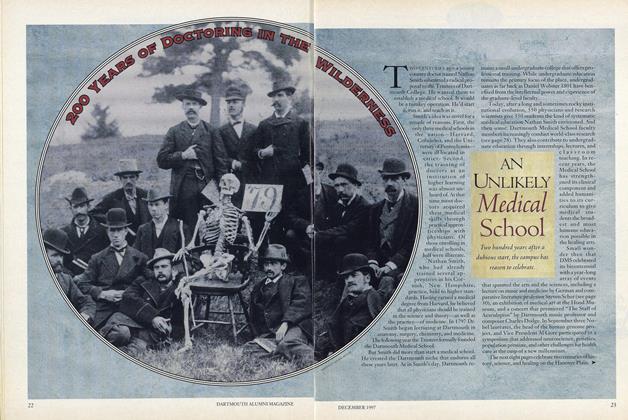

FeatureFENG SHUI COMES TO DARTMOUTH

July/Aug 2002 By ROBERT NUTT '49 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Tower Nighthawks

May 1994 By Ted Levin