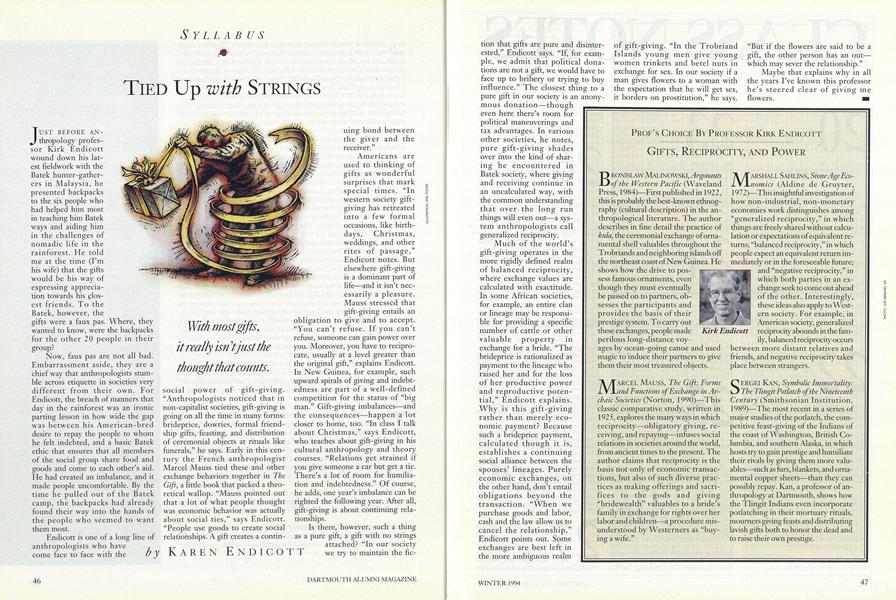

JUST BEFORE ANthropology professor Kirk Endicott wound down his latest fieldwork with the Batek hunter-gatherers in Malaysia, he presented backpacks to the six people who had helped him most in teaching him Batek ways and aiding him in the challenges of nomadic life in the rainforest. lie told me at the time (I'm his wife) that the gifts would be his way of expressing appreciation towards his closest friends. To the Batek, however, the gifts were a faux pas. Where, they wanted to know, were the backpacks for the other 20 people in their group?

Now, faux pas are not all bad. Embarrassment aside, they are a chief way that anthropologists stumble across etiquette in societies very different from their own. For Endicott, the breach of manners that day in the rainforest was an ironic parting lesson in how wide the gap was between his American-bred desire to repay the people to whom he felt indebted, and a basic Batek ethic that ensures that all members of the social group share food and goods and come to each other's aid. He had created an imbalance, and it made people uncomfortable. By the time he pulled out of the Batek camp, the backpacks had already found their way into the hands of the people who seemed to want them most.

Endicott is one of a long line of anthropologists who have come face to face with the social power of gift-giving. "Anthropologists noticed that in non-capitalist societies, gift-giving is going on all the time in many forms: brideprice, dowries, formal friendship gifts, feasting, and distribution of ceremonial objects at rituals like funerals," he says. Early in this century the French anthropologist Marcel Mauss tied these and other exchange behaviors together in TheGift, a little book that packed a theoretical wallop. "Mauss pointed out that a lot of what people thought was economic behavior was actually about social ties," says Endicott. "People use goods to create social relationships. A gift creates a continuing bond between the giver and the receiver."

Americans are used to thinking of gifts as wonderful surprises that mark special times. "In western society gift giving has retreated giving has retreated into a few formal occasions, like birth days, Christmas, weddings, and other rites of passage," Endicott notes. But elsewhere gift-giving is a dominant part of life and it isn't necessarily a pleasure. Mauss stressed that gift-giving entails an obligation to give and to accept. "You can't refuse. If you can't refuse, someone can gain power over you. Moreover, you have to reciprocate, usually at a level greater than the original gift," explains Endicott. In New Guinea, for example, such upward spirals of giving and indebtedness are part of a well-defined competition for the status of "big man." Gift-giving imbalances and the consequences—happen a lot closer to home, too. "In class I talk about Christmas," says Endicott, who teaches about gift-giving in his cultural anthropology and theory courses. "Relations get strained if you give someone a car but get a tie. There's a lot of room for humiliation and indebtedness." Of course, he adds, one year's imbalance can be righted the following year. After all, gift-giving is about continuing relationships.

Is there, however, such a thing as a pure gift, a gift with no strings attached? "In our society we try to maintain the fietion that gifts are pure and disinterested," Endicott says. "If, for example, we admit that political donations are not a gift, we would have to face up to bribery or trying to buy influence." The closest thing to a pure gift in our society is an anonymous donation though even here there's room for political maneuverings and tax advantages. In various other societies, he notes, pure gift-giving shades over into the kind of sharing he encountered in Batek society, where giving and receiving continue in an uncalculated way, with the common understanding that over the long run things will even out a system anthropologists call generalized reciprocity.

Much of the world's gift-giving operates in the more rigidly defined realm of balanced reciprocity, where exchange values are calculated with exactitude. In some African societies, for example, an entire clan or lineage may be responsible for providing a specific number of cattle or other valuable property in exchange for a bride. "The brideprice is rationalized as payment to the lineage who raised her and for the loss of her productive power and reproductive potential," Endicott explains. Why is this gift-giving rather than merely economic payment? Because such a brideprice payment, calculated though it is, establishes a continuing social alliance between the spouses' lineages. Purely economic exchanges, on the other hand, don't entail obligations beyond the transaction. "When we purchase goods and labor, cash and the law allow us to cancel the relationship," Endicott points out. Some exchanges are best left in the more ambiguous realm of gift-giving. "In the Trobriand Islands young men give young women trinkets and betel nuts in exchange for sex. In our society if a man gives flowers to a woman with the expectation that he will get sex, it borders on prostitution," he says. "But if the flowers are said to be a gift, the other person has an out which may sever the relationship."

Maybe that explains why in all the years I've known this professor he's steered clear of giving me flowers.

With most gifts,it really isn't just thethought that counts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

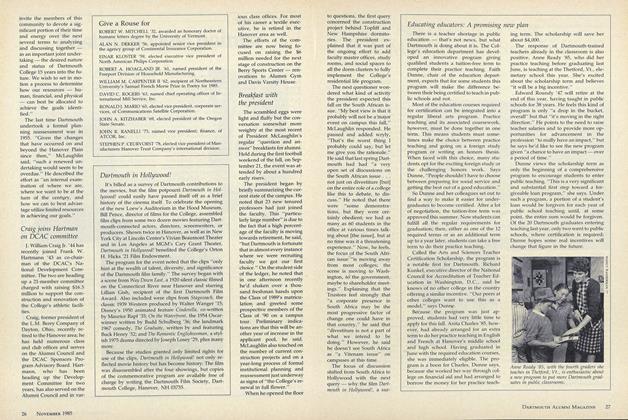

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWhat We Do Best

December 1994 -

Feature

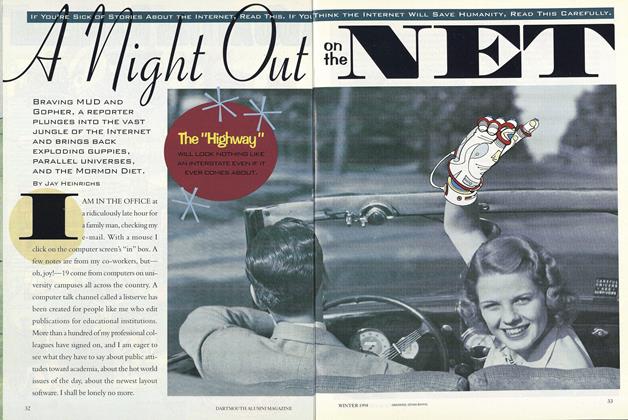

FeatureAnti-Social Climbers

December 1994 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1994 By E. Wheelock -

Article

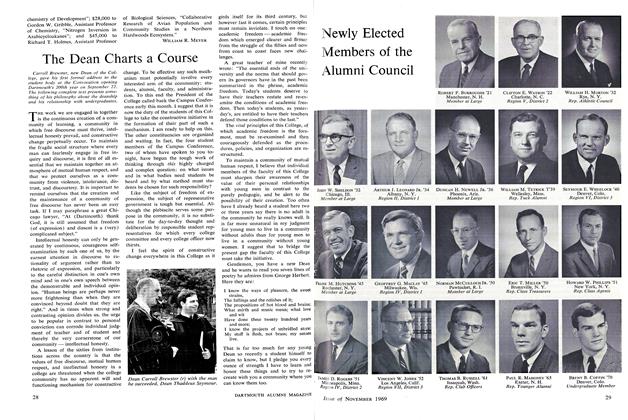

ArticleThe Overarching Concern

December 1994 By JAMES O. FREED MAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

December 1994 By Richard F. Perkins

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

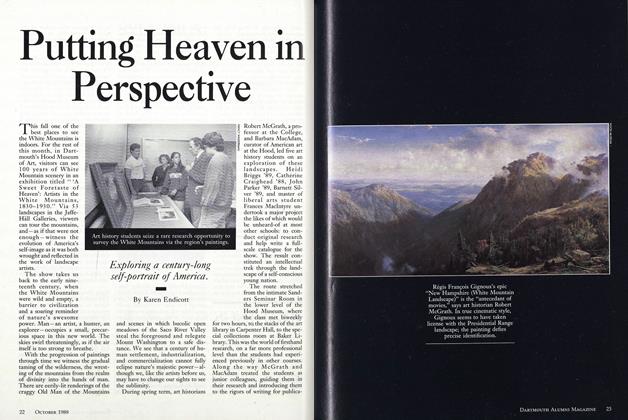

Cover StoryPutting Heaven in Perspective

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Hero in American Education

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleProfessor Sergei Kan:

September 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJapan's Ambivalent Story

OCTOBER 1988 By Mary Scott, Karen Endicott