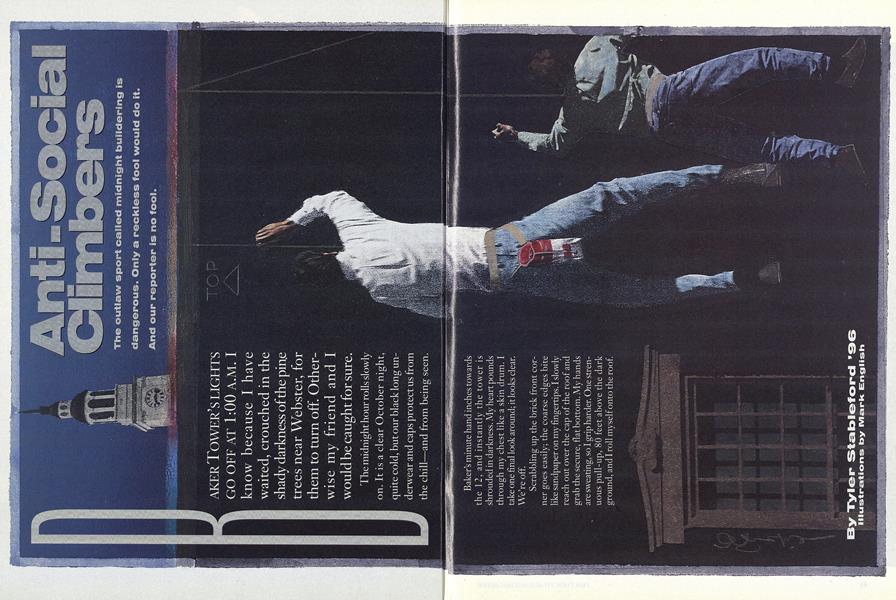

The outlaw sport called midnight builderlng isdangerous. Only a reckless fool would do it.And our reporter Is no fool.

BAKER TOWER'S LIGHTS GO OFF AT 1:00 A.M. I know because I have waited, crouched in the shady darkness of the pine trees near Webster, for them to turn off. Other- wise my friend and I would be caught for sure. The midnight hour rolls slowly on. It is a clear October night, quite cold, but our black long underwear and caps protect us from the chill—and from being seen.

Baker's minute hand inches towards the 12, and instantly the tower is shrouded in darkness. My heart pounds through my chest like a skin drum. I take one final look around; it looks clear. We're off.

Scrabbling up the brick front corner goes easily; the coarse edges bite like sandpaper on my fingertips. I slowly reach out over the cap of the roof and ' grab the secure, flat bottom. My hands are sweating, so I grip harder. One strenuous pull-up, 80 feet above the dark ground, and I roll myself onto the roof.

Crouching down, I scamper silently toward the center of the roof, away from the conspicuous edge. I exhale with a loud sigh; I must have been holding my breath without knowing it.

Seconds later, another hand grips the rooftop, and my partner pulls over the edge. Bending over like hunchbacks, we crawl along the series of gravel and copper roofs to the base of the clock tower.

It is dead silent. I want to howl in exhilaration. Far below, a few dorm lights are still on. On the Green, a few late-night stragglers make their way home. There is barely the sliver of a moon, but the white clock tower shines just above us with a dull, almost unnoticeable luminance. Soon we are standing on its balcony.

Actually, I don't think I should be revealing all this to you. Don't think of the narrator as me. I just wrote it that way. What kind of a freak do you think I am,, to climb up buildings and barely stifle a self in criminating howl? The sport, if you can call it that, is midnight buildering. The people who do it lunatics in the purest sense of the word are called builderers. You may call them rascals or mischief makers. For I do not want you to think that I condone or take part in this activity in any way. Buildering on the College's edifices is foolish, dangerous, and highly illegal. But from what I...fr0m what I am told, it is one heck of an adventure.

COME ALittle Closer and I'll tell you about it. Few people know about midnight buildering, because it is by nature silent and clandestine. Even fewer people have practiced it during its decades-long history.

There has always been a bit of playful climbing going on around campus. Who has not felt the urge to stand on top of the unlit Homecoming bonfire or the Carnival ice sculpture? But there is this other form of climbing.

You may have heard about the Mickey Mouse hands that students hung (more than once) on Baker's clock, or the flags placed atop the smokestack. This is the stuff I am talking about. But these deeds are the exception; most midnight builderers leave no trace of their passing. Usually there is no prank played, nothing moved. Nothing to take away from the experience but pints of adrenaline and stories to last a lifetime.

The urge to builder I am told comes on suddenly, usually after long hours of academic drudgery. The spirit comes on quickly, too strong to be ignored. It comes on like this. A student sits, bent over her desk, pen in hand. The problem set she is working on has been taking way too long, and her work is fall of scratches and cross-outs. "This sucks," she says, pushing her chair away from the desk. She glares at the wall, her brain a wash of numbers and equations. Suddenly she smiles. She stands up, grabs the phone, and makes a quick call. She grabs her dark sweatshirt and is out the door. Baker Tower, Webster, Dartmouth Hall, the Hop...the options are endless. If it doesn't move, climb it. Tonight the student and her partner will choose a tower or rooftop they haven't "done" yet.

Of course, Dartmouth students are not limited solely to the College's buildings. For some alumni the buildings they climbed most often were not on campus. "Smith and Wellesley dorm buildings were more common," says Andrew Harvard'71, "and not with a solely mountaineering purpose in mind."

After Baker Tower had been climbed this way and that, builderers began to search out other challenges. The smokestack is one of the biggest.

IT IS HARD TO WRITE about the smokestack. The 200-foot pinnacle has been the object of blatantly illegal activities, some of which have been costly to the College. Clearly visible from the Green, the lofty cylinder has served as a hanging post for an odd assortment of climbers' trinkets: flags, a 40-foot protest banner, a six-foot beer bottle. Climbers themselves have even managed to become "hungup," or stuck, on the smokestack's airy top. Many ascents have been made without notice. But the first became one of the most notorious in Dartmouth's history. It even earned a spot in a book by Dean Engle '92, Talus, A History of the DartmouthMountaineering Club.

It was January 1976 when two members of the class of '78, John Larson and Dave Jones, went into the night to begin their attempt. They brought an old Christmas tree to hang on the smokestack's summit. Jones and Larson prepared thoroughly, bringing ropes and protection hardware. When Larson began to lead up the insecure wire hugging the tower's side, however, the wind began to pickup. Larson felt his sense of balance shift. "I thought I was feeling queasy," Larson says in Talus. "But the whole damn thing was swaying back and forth."

Jones and Larson eventually reached the top late in the night. By this time the wind was howling and sleet began to fall. When the two juniors tried to haul the Christmas tree up their rope, it became stuck. Because of the cold, they decided to rappel immediately on a backup rope. But that line also became tangled around the tower, having blown in the wind. Jones and Larson were trapped.

Meanwhile the climbers had attracted the attention of a few students and campus security. The police were dumbfounded, and almost as helpless as Jones and Larson. "Get down from there!" the officers yelled fruidessly. They contacted the president of the mountaineering club, Peter Gilbert '76. They called the Hanover fire department to ask how long the hook and ladder reached. Not nearly long enough, was the answer. Finally they called Dick Shafer, associate dean of the faculty and advisor to the mountaineering club.

Shafer hurried to the scene and didn't do much at first to please the police. He burst out laughing. He howled and slapped his knee at the sodden climbers. "It was so fanny to see those clowns up there cursing the wind and everything else trying to straighten their ropes out," Shafer recalls in Talus. "The campus police thought we were absolutely awful. Here these guys were in danger...and all we were doing was laughing." Let the fools get themselves out of that mess, he told campus police. He and the group of student onlookers went to a bar and waited in the warmth for the climbers' return.

The two finally worked out their rope tangles after several hoursof cold thras of cold thrashing. Finally, as the tavern bell was sounding for closing time, Jones and Larson slinked in. "Man, they were a sad-looking bunch," Shafer says cheerfully. Instead of getting sympathy, they were told to buy the next round.

There are other stories that drift through the oral tradition of midnight buildering. Stories of police chases, and stories of peace- ful moonlit nights alone on Dartmouth's copper roofs. Some tales will never be told outside the builderers' circle.

College officials will tell you that Dartmouth Hall's bell has not been rung since 1930. Well, certainly not during office hours. But there are nights, dark and silent, when the iron CLANG might echo out across the Green. I have heard that sound, and I am almost sure it didn't come from Baker.

There are stories of another type I have overheard recently. Rumors about ventures below Dartmouth's buildings, to the depths of the College steam tunnels. Rumors, I am sure. They must be rumors.

The urge tobuilder I amtold comes onsuddenly, usuallyafter long hoursof academicdrudgery.

But there arenights, darkand silent,when the ironCLANG mightecho out acrossthe Green.

Ty Stableford is a Whitney Campbell Undergraduate Intern with this magazine, and a past president of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club. During theday he occasionally climbs the outside of Bartlett Tower which, say the deans,is perfectly legal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWhat We Do Best

December 1994 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1994 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleTied Up with Strings

December 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Overarching Concern

December 1994 By JAMES O. FREED MAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

December 1994 By Richard F. Perkins

Tyler Stableford '96

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2006 -

Feature

FeaturePrince Chiming

June 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleOn June 23 choreographer Moses Pendleton '71

October 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Cover Story

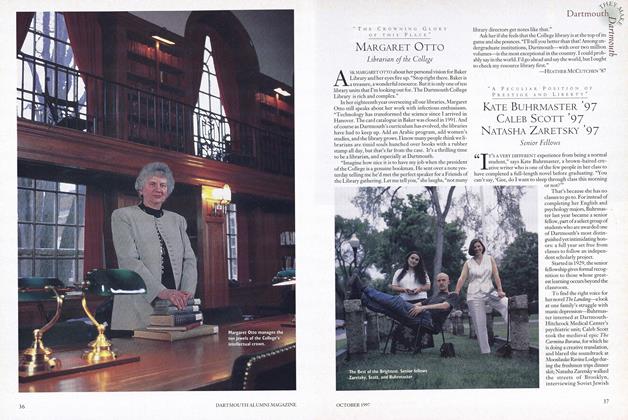

Cover StoryKate Buhrmaster '97 Caleb Scott '97 Natasha Zartsky '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleThe Delivering Duo

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Photography

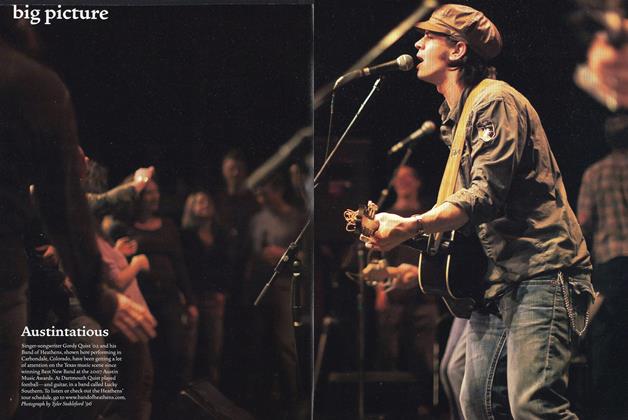

PhotographyBig Picture: Austintatious

Sept/Oct 2008 By Tyler Stableford '96

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Professional Schools

June 1980 -

Feature

FeaturePostwar Change in Dartmouth's Educational Program

APRIL 1966 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK FOR EVEREST BASS CAMP

Jan/Feb 2009 By PETER MCBRIDE '93 -

Feature

FeatureThree Staff Members Reach Retirement

JULY 1973 By ROBIN ROBINSON '24 -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham