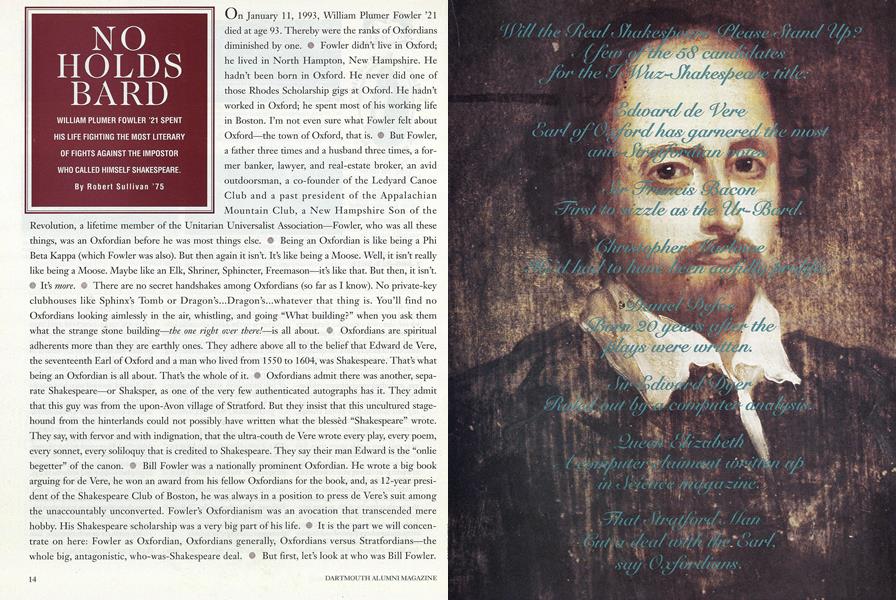

WILLIAM PLUMER FOWLER '21 SPENTHIS LIFE FIGHTING THE MOST LITERARYOF FIGHTS AGAINST THE IMPOSTORWHO CALLED HIMSELF SHAKESPEARE.

On January 11, 1993, William Plumer Fowler '21 died at age 93. Thereby were the ranks of Oxfordians diminished by one. Fowler didn't live in Oxford; he lived in North Hampton, New Hampshire. He hadn't been born in Oxford. He never did one of those Rhodes Scholarship gigs at Oxford. He hadn't worked in Oxford; he spent most of his working life in Boston. I'm not even sure what Fowler felt about Oxford—the town of Oxford, that is. But Fowler, a father three times and a husband three times, a former banker, lawyer, and real-estate broker, an avid outdoorsman, a co-founder of the Ledyard Canoe Club and a past president of the Appalachian Mountain Club, a New Hampshire Son of the Revolution, a lifetime member of the Unitarian Universalist Association—Fowler, who was all these things, was an Oxfordian before he was most things else. # Being an Oxfordian is like being a Phi Beta Kappa (which Fowler was also). But then again it isn't. It's like being a Moose. Well, it isn't really like being a Moose. Maybe like an Elk, Shriner, Sphincter, Freemason—it's like that. But then, it isn't. It's more. There are no secret handshakes among Oxfordians (so far as I know). No private-key clubhouses like Sphinx's Tomb or Dragon's...Dragon's...whatever that thing is. You'll find no Oxfordians looking aimlessly in the air, whistling, and going "What building?" when you ask them what the strange stone building—the one right over there!—is all about. Oxfordians are spiritual adherents more than they are earthly ones. They adhere above all to the belief that Edward de Vere, the seventeenth Earl of Oxford and a man who lived from 1550 to 1604, was Shakespeare. That's what being an Oxfordian is all about. That's the whole of it. ft Oxfordians admit there was another, sepa- rate Shakespeare—or Shaksper, as one of the very few authenticated autographs has it. They admit that this guy was from the upon-Avon village of Stratford. But they insist that this uncultured stage- hound from the hinterlands could not possibly have written what the blessed "Shakespeare" wrote. They say, with fervor and with indignation, that the ultra-couth de Vere wrote every play, every poem, every sonnet, every soliloquy that is credited to Shakespeare. They say their man Edward is the "onlie begetter" of the canon. Bill Fowler was a nationally prominent Oxfordian. He wrote a big book arguing for de Vere, he won an award from his fellow Oxfordians for the book, and, as 12-year president of the Shakespeare Club of Boston, he was always in a position to press de Vere's suit among the unaccountably unconverted. Fowler's Oxfordianism was an avocation that transcended mere hobby. His Shakespeare scholarship was a very big part of his life. It is the part we will concentrate on here: Fowler as Oxfordian, Oxfordians generally, Oxfordians versus Stratfordians—the whole big, antagonistic, who-was-Shakespeare deal. H But first, let's look at who was Bill Fowler.

HE WAS A MAN OF HAMPTON upon-the-Atlantic. His father, also named Bill, was a native of Concord, New Hampshire, who built a summer house in North Hampton in 1892. A decade later Bill the younger (never nicknamed "Will," by the way) was born at that seaside property.

Young Bill's father was a Dartmouth alum (class of 1872), and Dartmouth alumnicity has run in the Fowler clan: the patriarch Asa Fowler was class of 1833, and two of the younger Bill's uncles, three of his cousins, a nephew, and a son were Greeners. That son, Richard '53, was a Hanover fixture for years as he ran the Dartmouth Co-op from 1957 to '87; he lives today in Piermont, New Hampshire. The Fowlers have the granite of the Granite State in their muscles, their brains—everywhere!

Bill Sr. was a scholar and an apostle of literature; he and his sister were the donators of Concord's Fowler Library. It was in fact this man, our Bill's pater, who founded the Boston Shakespeare Club. "I inherited my interest in Shakespeare from him," Bill Jr. once said.

And he inherited it at a young age. He was a good student and was readily admitted to Dartmouth. In Hanover he listed toward the arts, and the out-of-doors. Actually, he did more than list—he was an absolute outdoors nut. He joined the Outing Club as a freshman, and that first year won a range of snowshoeing contests, from sprints to long-distance races. Fowler was always a man of absolutes, and he liked records. At midnight on May 14, 1919, he and a fellow sophomore, John Herbert, tried to set one: the College record for long-distance hiking in a single day. They chose for their route a stretch of mountainous New Hampshire terrain that had, along its way, several of the DOC cabins. They set off from Skyline Cabin in Littleton at a brisk four-and-a-half-mile-per-hour pace, breakfasted next morning near the East Branch of the Pemigewassett on raisins, cheese, and chipped beef, dined at a roadside farmhouse (75 cents each), and as the 24 hours expired they found themselves in the center of Lyme. They stayed there till dawn, having logged 66 miles.

Only upon returning to Hanover the next day did they learn that Warren Daniell '22, a measly 'shmen, had spent the weekend walking as well, and had covered 68 miles. Undaunted, the next May Fowler entered into a similar stunt, this time with future New Hampshire Governor Sherm.Adams '20 as his walking partner. Adams developed a stomach ache and Fowler twisted his knee on the hike, but they managed 83 miles and a new standard.

Daniell upped the ante shortly thereafter to 86 miles.

But enough of this I-can-walk-farther-than-you-can story.

In Fowler's junior year, he went for a walk in winter by the banks of the Connecticut. "I found a canoe that was so old it was rotted," he recalled a few years before his death. "I made myself a paddle and I went out on the river by myself."

He felt it was a shame that there was no one with him to share in the beauty. So upon his return he, joined by two buddies (Benjamin Farnsworth '2O and Allen Prescott '20), decided to form a canoe club. They named it after Dartmouth's patron saint of silly larks on the Connecticut, John Ledyard.

Let's pause for a poem.

Sonnet CXXXII The Old Ledyard Bridge (1859-1934)

Turn. back the years to when the Ledyard BridgeSpanned the Connecticut at Hanover;And in the valley, where from Occum RidgeThe hills of Norwich greet the villager,See the old covered bridge, with mid stone pierAnd weathered wooden walls of yesterdayDartmouth men and others traveled hereAcross the river on its seaward way!The train screams north along Vermont's curved shore,Leaving the Norwich station far behind,—Whence hurrying feet make resonant the floorOf the old bridge, where wheels or runners grind,With ringing hooves and sleigh bells of the past,Whose echoes fade in memories that last.

Fowler wrote that on October 6, 1957, and it was the 132 nd of the 148 sonnets he would write in his lifetime. (He could recite any of them by memory on his 90th birthday). Fowler was a wandering, thoughtful, minstrely kind of fellow. He was even more thoughtful, as a habit, than minstrel-y, but he was minstrely nonetheless.

"Following my graduation I attended Harvard Divinity School for nearly a year, long enough to become for the timebeing an agnostic," he said once. Divinity School was no place for a newly minted non-believer, so he switched to Harvard's graduate school of arts and sciences. He then taught school for a year in Mohonk Lake, New York. He got married and returned to Harvard, this time to the law school. He was admitted to the bars of Massachusetts and New Hampshire and embarked upon a successful four-decade legal career, specializing in probate and real-estate matters. He split his time between Boston and his beloved Little Boar's Head in North Hampton where, in 1937, he built a house on the same Atlantic Avenue plot of land where his father's house had once stood, and where he himself had been born.

He loved writing poetry. He published two volumes of naturalistic verse in the forties; they seem to have frost in them, frost on them, and Frost all about them.

He loved working in his vegetable garden.

He loved researching the history of Hampton.

And all the while, he loved Shakespeare.

That is to say, he loved the works of Shakespeare. He thought precious little of the worm, the cur, the impostor, the...well, let's let Fowler describe the man:"the barely literate theatre-worker, William Shaksper(e) of Stratford." (Parentheses are Fowler's.)

Fowler accused "the Stratford man" (as Oxfordians persistently refer to the man from Stratford) of perpetrating "the biggest and most successful fraud ever practised on a patient world." He accused him of this early, late, dawn-to-dusk—at every opportunity. This is the way it is with the 400 American Oxfordians (they have a club!) and the hundreds more worldwide. They hate the Stratford man. He is the bogey man. He is the usurper. He is the devil incarnate. He is the great Satan!

What was it that he did to gain their wrath?

Well, probably, the way they figure it, what he did was: He entered into a deal with their cherished Edward.

De Vere, whose motto oddly enough was Vero nihil verisns (Nothing truer than truth), was a nobleman of high standing, great erudition, and some youthful talent for poesie. At a certain point in his life, he stopped writing verse and spent the rest of his days doing noble things.

Or did he?

Perhaps he kept writing?

Perhaps he wrote great plays?

Perhaps he wrote lots of sonnets?

Perhaps since theater was a low-rent item in Elizabethan England—certainly nothing that Mr. Shiny Tights Nobleman would want to dirty his hands with—ol' de Vere figured he'd better travel incognito if he was going to continue to pursue this writin' thing?

So perhaps, just perhaps, he asked this fellow Shaksper— this Stratford man, lately arrived at London Towne from Nowheresville-upon-Avon to pursue work in the theater—to front for him, be his beard. Be, as it were, his Bard.

Sounds reasonable.

Sounds to Oxfordians a lot more reasonable than that a lowlife with no findable background in education could generate prose and poetry that remains the most beautiful and profound in the history of a language.

LET US NOTE BEFORE CONTINUING ANY FURTHER: Lots of things sound reasonable.

For instance: the Red Sox will win the World Championship in our children's lifetimes. This sounds reasonable. And Edward de Vere was Shakespeare because he was cultured, attendant at court, well-traveled, possessed of Hamletesque angst, poetic. This sounds reasonable.

But we should point out here and now: There have, through the years, been no fewer than 58 claimants to the I Wuz-Shakespeare title. Fifty-eight! Fifty-nine if you count my own dear departed great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather Sullivan ("Sulavan" in an existing autograph), who actually was Irish, not English, but sure did enjoy plays—or so we're told.

Fifty-eight (or nine)! And to some folks, each one of them sounds (or has sounded) reasonable. The first to sizzle as the Ur-Bard was Bacon, and Sir Francis still has a fan club today. Christopher Marlowe was Shakespeare, many have said, though how he could have written his own plays and all of "Shakespeare's" during his tragically cut-short life remains a mystery. Ben Jonson was Shakespeare. Herbie Bagadonuts was Shakespeare. Anyone but Shaksper was Shakespeare.

And that's the thing, you see: People dig up these other Shakespeares because Shaksper just couldn't have been Shakespeare. No way, no how. That man from Stratford, that tanner's son, must have been, well, stupid. And, the Spinal Tap theorem notwithstanding, it is not a fine line between brilliant and stupid, it's a big, heavy, black, uncrossable line. Marlowe, Jonson, and even de Vere were certifiably brilliant, and therefore they could have been Shakespeare. The bozo from the boonies—not a prayer.

If he could not have been, then who might've been? These 58 others.

You see? That's what it all grew from, an inability, as Ralph Waldo Emerson once put it, to "marry" the insubstantial man from Stratford with the body of work. And so we have been delivered, in the last century and a half, of 58 Shakespeare lookalikes. We've been presented with candidates who were precisely contemporaneous with Shaksper, candidates whose lifetimes roughly coincided with his (de Vere died a decade before the final plays were performed), and—rather astonishingly—candidates who weren't even Elizabethans.

These wannabes have all cropped up in the last century and a half. It's interesting that Shakspet went uncontested as Shakespeare for nearly 200 years following his death. Then, in the 1780s, the Reverend James Wilmot sought to gather information for a biography of Shakespeare, covering himself, according to one who reported on Wilmot's researches, "with the dust of every private bookcase within a radius of 50 miles" of Stratford. Wilmot found nothing that had been owned, touched, or written by the great man. Moreover, he found no incidental writings about the great man. Wilmot stands as a rarity in this story: He was a scholar who did not want to stir things up. He burned his notes in the realization that they held volatile implications. Wilmot once whispered to a friend that "some other person" might have been the Bard. He suggested Sir Francis Bacon.

In 1857, Delia (No Relation) Bacon wrote a book that did more than suggest this, it claimed it as a certainty: Sir Francis was the onlie begetter. No less than Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the laudatory introduction to Delia's volume, and Mark Twain subsequently said that his doubts about Shaksper were "born of Delia Bacon's book." Walt Whitman, Henry James, and Sigmund Freud, as well as Emerson were among the first notables to voice what are called "Anti-Stratfordian beliefs."

This background on the great debate comes from a lengthy October, 1991, series in The Atlantic entitled "Looking for Shakespeare." The Atlantic noted that "credit for the opening public salvo in the debate is given to Delia Bacon," and that her book was the cornerstone of what would become a veritable industry, the Authorship Question Industry. In the 19905, said The Atlantic, "The Anti-Stratfordians are not discouraged...and during the past few decades a solid majority of them have coalesced behind Edward de Vere (1550-1604)."

The two main essays in The Atlantic were by a leading Oxfordian, Tom Bethell, and a prominent Stratfordian, Irvin Matus. Each laid out the theories briefly sketched above: that an uneducated man couldn't have concocted the canon, that Oxford went to all the right places and was frequently at the right courts, that the character Hamlet reflected de Veres own torments; and then, contrarily, that there's no hard evidence for Oxford, that Shakespeare cribbed his plots from published histories and therefore didn't have to go to Italy or France or wherever, that Anti-Stratfordians are simply disbelievers in the randomness of genius, that de Vere died before several of the plays even appeared, and that the Oxfordian contention that these plays were performed posthumously is both desperate and specious. Then Bethell and Matus each rebutted the other. The debate, as conducted in The Atlantic, was entertaining and cordial—far more cordial than tire authorship fight has been in other forums.

Bethell concluded with lines from Sonnet 76 that are favorites of Oxfordians:

That every word doth almost tell my name,Showing their birth, and where they did proceed.

Bill Fowler believed in the message he read between those lines. He believed in it strongly and for a long, long time.

When he withdrew the shingle from his Boston law shop in 1971 he began to delve ever more deeply into the messages, implications, insinuations, inferences, hints, clues, and mysteries that can be seen to swirl 'round Shakespeare. Throughout the seventies and eighties, "Shakespeare" and Oxford were Fowler's constant companions. He served as president of the Boston club from 1972 to 1984, and all that time he was researching his big book on the authorship question. He said during these years that he hoped to live until he was 83, citing 83 as the number of miles he and Adams had once hiked, and figuring he could finish his tome by then. It's lucky he lived longer, for the bulky green book Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford's Letters was not published until 1987 when Fowler was 86 years old.

Dick Fowler recalls that the old man's passion for Oxford peaked during this period. "He didn't get around to the book until he was an advanced age and, oh gosh, every living minute was consumed by it once he'd started," says the son. "He'd get exercised about it, it got him wall-eyed. A lot of people wouldn't even hear all this stuff about Oxford from him, but of course the family had to believe it. I'll tell you, I'm not into this whole thing—the question, you know—but at dinners, he'd just start going on, 'This is the greatest hoax ever perpetrated...' and I'd say, 'Dad, you told me that at least a hundred times.'

"He poured it all into his book. It's a big book. You either believe it or you don't, but it's a substantial book."

It is that. When I stand alone on my bathroom scale I weigh...well, never mind that. But when I stand with Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford'sLetters I weigh 5.5 pounds more. It is 872 pages long, and they're big, dense pages the kind that the books in a Peter Bien Comp Lit class always had.

I skimmed it. I've got a job, so all I could do was skim it. Sorry.

Fowler was proud of the book, and he should have been. In the preface he said his research would "supply the missing documentary evidence that advances Oxford's authorship of Shakespeare from theory to reality and delivers a coup de grace to the long-established Stratfordian theory....From here on in, it's just a question of corroborating evidence."

I will say this: If you go into the thing already believing in Oxford, Fowler's masterwork seems to deliver on its boast. If you go in as a Stratfordian, it'll start you wondering.

It started me wondering.

It started me thinking about something that Bill Fowler himself once said, about why he had become so devoutly involved in the authorship question. "I felt," he said in 1986, "I wasn't being treated right when I was taught something that might not be true. I am interested in truth."

Well I, for my part, wasn't all that interested in truth. Early in this authorship inquiry I figured I wasn't necessarily going to arrive at truth if I pursued Shakespeare from here to doomsday. But I wanted answers, I wanted at least some answers. Bill Fowler's book spurred me to seek a few answers.

So I did exactly what I used to do in Hanover when I had a question about Shakespeare. I called Dave Kastan.

Dave was a Bard prof when I was an English major; he split the canon down the middle with Peter Saccio, and it was a golden age for undergrads who wanted to dip into the compleat Shakespeare. Dave has since moved on to Columbia, which makes me a bit sad but makes him very happy because, although not tall, he's a basketball freak and—let's be frank—Columbia hoops is to Dartmouth hoops what Green gridders are to Lion...Well, it's not that bad, but you get the point.

Anyway, Dave lives with his wife (Susie Van Wie 77) and their child on the upper-Upper West Side, and I called him one night and asked, Hey, what about this Earl of Oxford?

"Ha!" said Dave.

I asked: " Dave, what does 'Ha!' mean?"

Dave elaborated on "Ha!":

"The argument for the Earl—or any of the other 'Shakespeares'—is an argument born out of a kind of snobbery. It's people who have this touching faith in a university education. 'No one could have done this who wasn't highly educated.' They say Shakespeare couldn't have had the knowledge of court customs, but really, the stuff in the plays could have been gleaned from books. Furthermore, if you want to go about it that way, there's stuff in the plays about country customs that some Earl of Oxford wouldn't have known.

"Oxford died in 1604, so the claims for him seem pretty desperate to me. The other thing that's really rather ridiculous is that the Anti-Stratfordians say there's this conspiracy among academics to protect the guy from Stratford. I'll tell you, any one of us conspiratorial academics would have a made career if we could lay out conclusive proof for someone else.

"How many claimants is it now?" Kastan continued.

"Fifty-eight," I offered helpfully. "Some say fifty-nine."

"You hate to make fun of these guys because they're very earnest, but...You know it was a guy named Looney who founded the de Vere theory? And did you know that someone boosted Defoe? Which is astonishing because Defoe was born about 20 years after the plays were written. The Defoe advocate's name was Battey. And then Silliman wrote the big book that staked a claim for Marlowe. Looney, Battey, and Silliman—what does that tell you?"

I politely asked my former professor, who used to hold my grade in his hands, to get serious.

"Well, seriously, this whole thing is the displacement of a real question. You can't answer the question of genius, and so you put it off to a question that you can answerauthorship. It's a search to explain what's inexplicable."

Aha, I said to myself. It's like this: Is it any more remarkable or even incomprehensible that a tanner's son from the English countryside wrote these plays than it is that Mozart did what he did at age ten? Is it any more unfathomable? And just because Mozart left a better paper trail, does that mean Shaksper wasn't Shakespeare?

This made me go, Hmmmmmmm.

PROFESSORS ARE ONLY PROFESSORS. COMPUTERS are supposed to be correct.

This could have been anticipated: that as our civilization slid into its modern age, computers would be enlisted in all arguments, the Battle of the Bard among them. And so it has come to pass. Computers have, in the past several years, been fed all sorts of patterns and statistics, such as how many times this word appeared in Shakespeare, how many times that one did, how often this phrase or construction was used, how often that one. In one experiment , conducted by Professor Ward Elliott of Claremont McKenna College, the poetry of Shakespeare was tested against that of 30 other writers. Elliott hoped to find a "voice print" that matched Shakespeare's. As a mild Oxfordian he mildly hoped that the voice print would belong to de Vere. But it did not. In fact, Bacon, Marlowe, and Sir Edward Dyer, another claimant with many supporters, were

similarly ruled out by Elliott's research, and all of them in the first round. Embarrassingly for Elliott (he takes the hit, because computers do not blush), among those still standing for the Round Two bell was Queen Elizabeth Herself. ("Did Queen Write Shakespeare's Sonnets?" asked a headline over a news brief in Science magazine.) Subsequent investigation by Elliott and his machine proved that Queen Liz, too, was not Shakespeare. It did not prove conclusively who was. Elliott told The Atlantic what he had learned for sure: "If the glass slipper doesn't fit, it's pretty good evidence that you're not Cinderella. But if it does, that doesn't mean that you are."

Don't get gleeful yet, you anti-techno proto-romantico so- and-sos, ye believers in brain over bytes.

The Atlantic reported farther that a computer experiment by Donald Foster, professor of English at Vassar, had yielded conclusions that were not only not laughable but that seemed to produce information of much value to Shakespearean scholars. Foster knew, as everyone knows, that Shakespeare was an actor who appeared in his own plays. Foster knew as well that there was seventeenth-century evidence that Shakespeare had, without a doubt, appeared as the ghost in Hamlet and as Adam in As You Like It. Foster knew finally that the several other roles assumed by the Stratford man were either disputed or were a mystery.

Foster realized, as have many Shakespeare scholars, that the first appearance of certain words—words that the playwright hadn't yet used in his career—often appeared as a cluster. That is to say: Shakespeare tried out a lot of new words in one place or in one speech in a play, and then in a later play the words, which now had become part of his theatrical vocabulary, were sprinkled about. "In one role," Foster told The Atlantic, "there would be two to six times the expected number of rare words." He theorized that the character speaking the cluster was, in each case, the actor Shakespeare. The playwright (goes Foster's theory) had given himself the assignment of trying out the newly learned lingo.

Foster fed this idea into the computer. "The results," he told The Atlantic, "have been absolutely stunning." Foster's computer correctly identified the Adam and Hamlet's father's ghost roles as Shakespeare's. It added Theseus in MidsummerNight's Dream, "Chorus" in both Henry V and Romeo andJuliet, John Gower in Pericles, Bedford in Henry VI, Part I, Suffolk in Henry VI, Part II and Warwick in Henry VI, Part III. Sometimes Foster's computer claimed two roles in a single play were Shakespeare's—Gaunt and a gardener in Richard II, for instance. In these cases, it eventuated that the characters were never on stage together. Moreover, in most cases the character ascribed to Shakespeare by the computer was the first to appear in each play, which seemed to make sense: The playwright strides out, receives acclaim, gives a speech—trying out some new verbal trickery as he does so—then retreats to watch the performance .

The larger point is: Computers can be and have been inconclusive. They also can be, and have already been, pretty darned conclusive. When the right program for the authorship question is written, will the machine finger the proper Bard? Elliott, unabashed, thinks it might. He told The Atlantic that he believes the bias against computer modeling in literary studies will shrink: "The walls are sure to crumble, just as they did in baseball and popular music....Some high-tech Jackie Robinson will score a lot of runs, and thereafter all the teams in the league will praise the newest touch as ardently and piously as they now shrink from it."

Some teams surely will. An interesting question for us, since this is a piece about impossible-to-answer questions, is whether our participant in this game, W.P. Fowler '21, would have been among the players on "all the teams in the league."

WE'LL NEVER KNOW, OF COURSE, BECAUSE AS was mentioned several thousand words ago, Fowler died in January 1993. He had lived a good, fruitful, long, minstrel-y life, and so this can't be seen as a bad or even an unduly sad thing. In fact, in considering this computer program and its seeming success, it can be argued that Fowler lived at the right time, and died in the nick of it. He was a lawyer with a poetic bent, an avocational spinner of sonnets. He lived when human intellectual investigation was a stimulating and fun pursuit that did not involve electronics. He died as the computers were about to intervene.

Shakespeare, whoever he was, clearly felt that man was an animal of complexity and many moods, and that there were two—or 20, or 200—ways to look at affairs involving man. Throughout the twentieth century, we have been trying to cut those numbers. And throughout the twentieth century, the battle between Oxfordians and Stratfordians, resisting this modern urge, has taken on a Shakespearean tinge, a sense of multiplicity, of not-quite-sureness, of realness: You say yes, I say no, you say why, and I say I don't know. (Well I guess that's a John Lennon tinge, but geniuses think alike, as this whole brouhaha suggests at bottom.)

Debate: It's a healthy thing. The "fight" that Fowler was part of was an intellectual arm-wrestling competition among smart people. It was stimulating and thought-provoking. It was worthwhile. Let's say for a moment that Fowler was wrong about Oxford. Okay, he was wrong. Nevertheless, all of the thinking he did about this question, all the good research, all the dinnertime discourse, all the writing, all the tonnage of Shakespeare Revealed inOxford's Letters—all of it still was worthwhile. It was scholarship. It was intellectual inquiry. It was the one of the things we all went to Dartmouth for.

Fowler was a good and able teammate on the Oxfordian side. He enjoyed the fray. It filled his cup. Shakespeare was his reading, his murder mysteries, his golf, his tennis, his cocktail. He got a kick out of making the argument. Let's say for a moment that Fowler was right about Oxford. I still say Bill got out while the getting was good. If the computers of 2001 anoint with certainty Fowler's man Oxford as the "onlie begetter," it is just as well that Fowler won't be around to learn of it. He wanted truth, but...

Without the fight, whatever would he have done in the morning, upon waking? Hi

Will the Real Shakespeare Please Stand Up? A few of the 58 candidates for the J-Wuz-Shakespeare tile: Edward de vere Earl of Oxford has garnered the most anti-Stratforlian votes Sir Francis Bacon First to sizzle as the Ur-Bard Christopher Marlowe He'd had to have been awfully prolific. Daniel Defoe Born 20 years after the plays were written. Sir Edward Dyer Ruled out by a computer analysis. Queen Elizubeth A Computer Clainant written up in Science magazine That Stratford Man Cut a deal with the Earl say Oxfordians.

Bill Fowler

Considering this computer program and its seening success, it can Be argued that Fowler lived at the right time, and died in the nick of it.

Marlowe, Jonson, and evend de Vere were Certifiably brilliant and therefore they could have been Shakespeare. The bozo From the boonies-not a prayer.

Francis Bacon

Christopher Marlowe

Robert Sullivan is a contributing editor of this magazine. Hetries out new vocabulary words as an editor at Life magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

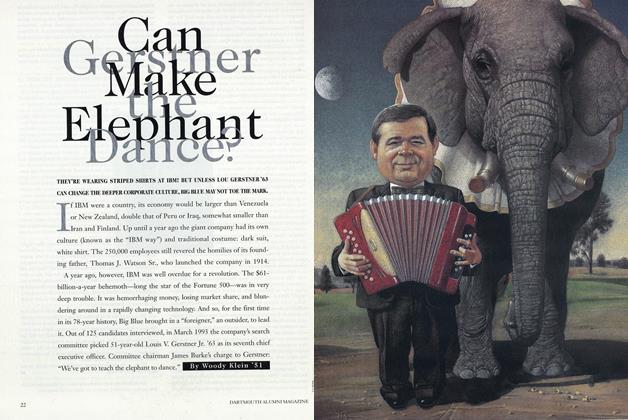

FeatureCan Gerstner Make the Elephant Dance?

March 1994 By Woody Klein '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

March 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

March 1994 By W. Blake Winchell -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

March 1994 By Christopher K. Onken -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

March 1994 By Morton Kondracke

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

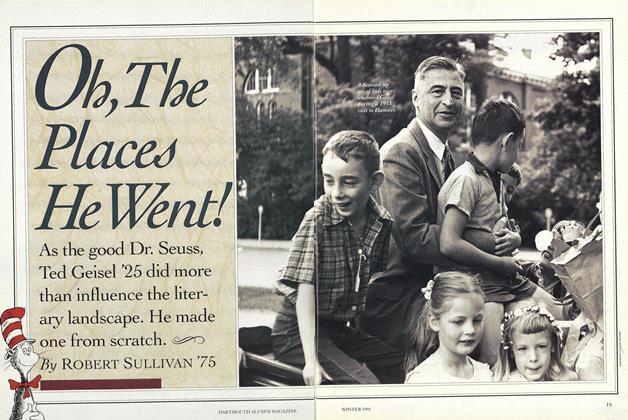

Cover Story

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Trophy Finally Stays Put

February 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticlePosthu-Mously, Norman Maclean Takes On a New Element

February 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

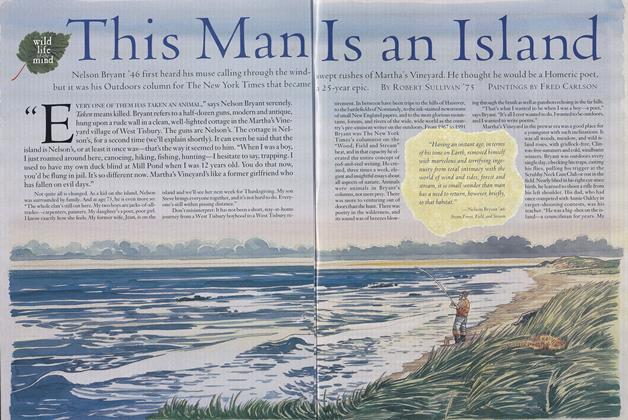

Feature

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

FEATURE

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

Features

-

Feature

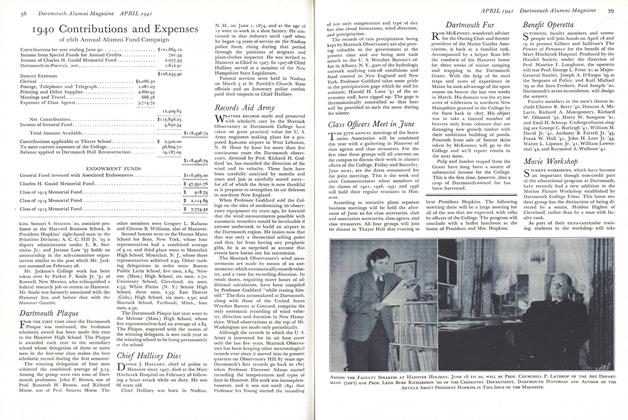

Feature1940 Contributions and Expenses of 26th Annual Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

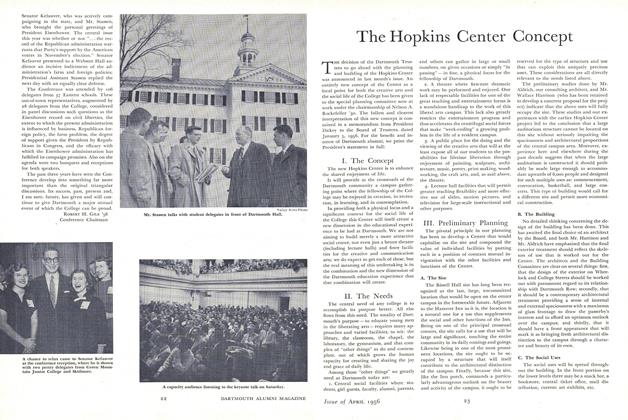

FeatureThe Hopkins Center Concept

April 1956 -

Feature

FeatureHigh School Principal

DECEMBER 1966 -

Feature

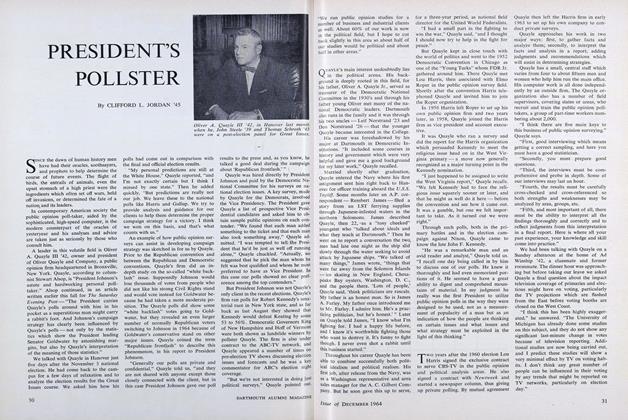

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

DECEMBER 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

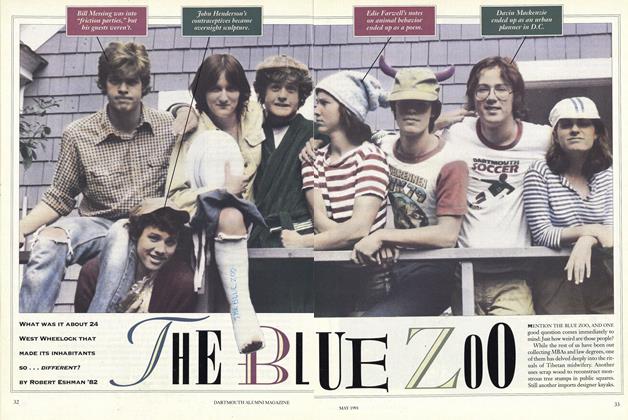

FeatureTHE BLUE ZOO

MAY 1991 By Robert Eshman '82