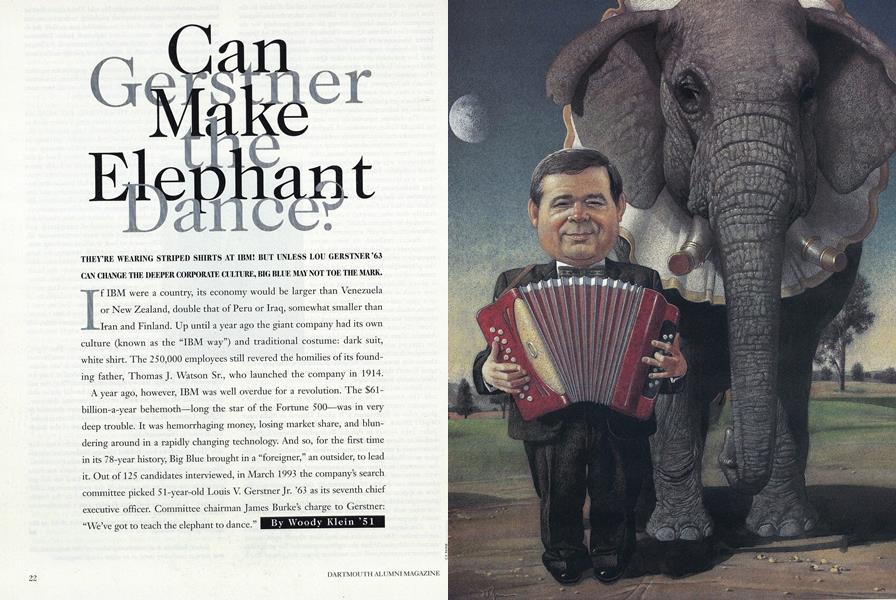

THEY'RE WEARING STRIPED SHIRTS AT IBM! BUT UNLESS LOU GERSTNER '63 CAN CHANGE THE DEEPER CORPORATE CULTURE, BIG BLUE MAY NOT TOE THE MARK.

If IBM were a country, its economy would be larger than Venezuela or New Zealand, double that of Peru or Iraq, somewhat smaller than Iran and Finland. Up until a year ago the giant company had its own culture (known as the "IBM way") and traditional costume: dark suit, white shirt. The 250,000 employees still revered the homilies of its founding father, Thomas J. Watson Sr., who launched the company in 1914.

A year ago, however, IBM was well overdue for a revolution. The $61 billion-a-year behemoth—long the star of the Fortune 500—was in very deep trouble. It was hemorrhaging money, losing market share, and blundering around in a rapidly changing technology. And so, for the first time in its 78-year history, Big Blue brought in a "foreigner," an outsider, to lead it. Out of 125 candidates interviewed, in March 1993 the company's search committee picked 51-year-old Louis V. Gerstner Jr. '63 as its seventh chief executive officer. Committee chairman James Burkes charge to Gerstner. "We've got to teach the elephant to dance."

BUT BEFORE IT CAN DANCE IT MUST LOSE SOME weight—and, while it's at it, learn a new tune. Lou Gerstner arguably has the toughest corporate job in America today. The IBM he inherited was a dysfunctional company—one that had taken $28 billion in writeoffs since 1986, and saw its stock fall 75 percent from its peak in 1987. Its market share had been slipping steadily. It lost nearly $7.8 billion in 1991 and 1992—twice the gross national product of Bolivia. Even now, a year after Gerstner took over, industry analysts say the odds are against him. No well-established corporate executive could have taken a bigger risk. In statesmanlike fashion, Gerstner asserted that he took the job and its $3.5 million annual compensation (plus stock options) because "it was important for the vitality of the country."

The anointment of Gerstner in the New York Hilton last March revealed a striking contrast in leaders. Outgoing CEO John F. Akers looked tense, pale, and tired. Akers, a 58-year-old Yale man and former navy pilot, had risen through the ranks during 33 years with IBM. Gerstner, on the other hand, looked tanned and physically powerful. "Brilliant and steely," The New York Times judged him. "He has the guts to slash and burn, said Business Week. At the Hilton press conference Gerstner wore an un-IBM-like eggshell blue shirt and exuded the confidence that years before had attracted his classmates attention at Dartmouth.

Gerstner grew up in a middle-class Catholic home in a Long Island suburb, went to a parochial school (which he has since endowed), and entered Dartmouth in 1959. He was a campus leader of sorts: Kappa Sigma, Palaeopitus, class treasurer, Interdormitory Council, Newman Club, Undergraduate Council, Judiciary Committee, Casque & Gauntlet, crew, WDCR. He was an Alfred P. Sloan National Scholar. Classmates remember him as an intense student. "I knew he was going places," says class secretary Harry Zlokower '63, who owns a public-relations firm in New York. "A workaholic," adjudges Lawrence B. Bailey '63, a lawyer and a Kappa Sig brother in Seattle, Washington. Bailey, who represents rival Bill Gates of Microsoft, remembers that Gerstner "spent an incredible amount of time studying. He literally lived in the 1902 Room in Baker. It was an elegant room and the serious students reserved chairs there.

"What was amazing about Lou is that he was also very active in campus politics," Bailey adds. "The guy just showed up for elections and won because he was so capable and popular. He basically socialized on weekends. He was very personable but you did' not see a great deal of him. His number-one commitment was to be a good student."

"As far as fraternity activities went, he would be in the middle of things as opposed to being a nerd," says Kappa Sig brother Robert Baxley Jr. '63 of Pensacola, Florida, who works as a research fellow for Monsanto Chemical. "I remember playing a lot of beer-pong doubles with him. That's where you set up glasses of beer on the four quadrants of a ping-pong table. You served diagonally across the table. If you hit the other guy's glass when you served, you had to drink. If you hit the other guy's glass when you returned a shot, they had to drink. If you sank the ball into the glass, you had to drink the whole glass. He was competitive. I saw him at our tenth reunion. We even played a little beer-pong. We were disappointed he didn't come to our 25th."

Gerstner graduated Phi Beta Kappa as an engineering major and went on to earn an M.B.A. at Harvard Business School. In 1965 he joined the blue-chip consulting firm of McKinsey & Cos., where he rapidly built up the firm's financial-strategy practice, ignoring complaints from older partners that the young upstart was making a lot of waves. By the time he was 31 he had made senior partner—the youngest person ever to reach that rank at McKinsey.

He jumped to American Express as executive vice president in 1978 and immediately overhauled the credit-card business, later rising to the corporation's presidency. At American Express, incidentally, he was a big IBM customer. "He may not understand bits and bytes as well as some people, but he understands the role technology plays in solving problems, says Richard Thoman, a former Nabisco marketing executive whom Gerstner brought into IBM as a senior V.P. in December. By the time Gerstner left in 1989 to become chairman and CEO of RJR Nabisco Holdings Corp., the number of American Express cards had doubled and credit-card spending had increased five-fold.

At RJR Nabisco he pared debt, slashed expenses, and sold off assets. He worked six-and-a-half-day weeks and told reporters, "I'm having a terrific time."

The workaholic must be having the time of his life these days. "The future of IBM now lies with an extraordinarily driven manager known for his iron will," the Wall Street Journal wrote recently. The Journal said the answers to three crucial questions will determine how he fares as IBM's CEO: "Can he quickly master a new industry? Can he transform a stodgy corporate culture and inspire the people who make up IBM? Can he rebuild shareholder value by separating the winners from the losers in IBM's tangled mass of overlapping businesses?"

Gerstner's plan is to reverse the company's recent tendency to split itself up into semi-autonomous parts, and instead link corporate elements more closely. Gerstner wants to reestablish IBM as the computer company (remember the saying of not-so- long ago that you couldn't get fired for buying IBM equip- ment?). The company will stay in the mainframe business, but the giant computers will no longer be the corporate mainstay. Centerpiece of IBM's battle to win the technology war is the Power-PC, a microprocessor that is coming onto the market this spring, built into many home and office computers. The new chip is made to run a wide variety of software and operating systems simultaneously, including DOS, Windows, and Macintosh. "Make no mistake about IBM's investment in the Power-PC from its Motorola/Apple alliance," says Sam Albert, a nationally known industry consultant in Scarsdale, New York. "It's huge. And it represents IBM's view of the future." Nevertheless, he notes that giant Intel corporation will remain the primary supplier of the silicon brains behind IBM machines. The Power PC's technology appears to be better than Intel's new champion chip, the Pentium. But by continuing to buy Intel's chips, Albert says, "IBM is playing both horses."

Gerstner's very first move, however, was not electronic but symbolic—he dismissed the vice president for communications and replaced her with David Kalis, a long-time advisor who had headed communications at RJR Nabisco. Gerstner has since brought in a cadre of other new faces, including the treasurer, Frederick Zuckerman, another former Nabisco colleague. These moves lead some analysts to question whether Gerstner is replacing IBM's inbred management culture with his own brand of insularity—"The Oreo Society," one consultant called it, referring to one of Nabisco's best-known products.

In another gesture that sent a clear message of change to IBM employees, he suspended publication of Think, the company's four-color magazine, and replaced it with a flashy, tabloid- sized newspaper that resembles USA Today. The explanation on the inside front cover: "The new Think reflects the new IBM— committed to being candid, open, relevant, and customer-ori- ented." In the first issue last September he listed his top priorities: To "right-size" IBM as quickly as possible; to "win more battles on the customer's premise"; and to work on some important strategic directions for the company.

Since then he has restructured senior management and executive pay and shifted IBM's bureaucracy. Last July he announced he would cut a quarter of the workforce—60,000 people—and get rid of $8.9 billion worth of factories and equip- ment. He said he wanted to avoid "the Chinese water torture" of piecemeal payroll cuts—a pattern IBM had been following prior to his arrival. "To keep slicing quarter after quarter, year after year, laying off people. I mean, it's awful!" he declared. In other moves to bolster IBM's bottom line, he has sold off some units, most notably the company's Federal Systems Division; and he may close down the company's plush world headquarters in Armonk, New York.

Insiders give the changes mixed reviews at best. They say that while Gerstner has made his presence felt, daily corporate life has not been altered much. "Gerstner has hit Armonk like a bolt of lightning," said one executive who just retired. "But cutting staffs and streamlining things there is a drop in the bucket. Sure, people now wear blue and striped shirts and sport clothes. But many still think and act the same as they always have. That's the real change that has to be made."

Gerstoer admits that he has inherited a major attitude problem. "You know what people tell me in this company? It's easier to do business with outsiders than with people inside IBM. That's got to change." In a not-so-veiled threat to those who will not change, Gerstner says: "We have to sort out who wants to be part of this new culture. For those people who simply don't want to be part of this complicated, integrated business—where the price of admission is being a team member—well, then, they probably ought to go somewhere else. But they're also going to miss out on one of the great rides of all time!"

Some of the change can already be seen in the field. "It's not at all like headquarters," reports a veteran IBMer who transferred to a field operation from Axmonk last year. "Here, good God, when a customer calls, the guy in charge runs out of the office with a few people and gets to the customer in a hurry. This is the real world. The customer is the most important person in our lives. I think IBM is finally on the right track. From what I see and hear, Gerstner is getting around the company."

"Getting around" is the operative phrase. To reach the rank and file, he meets them without their managers and tours plants and offices; and he likes to talk to large IBM gatherings, leaving plenty of time for questions. Unlike his predecessor—who was called "Mr. Akers" within the highly structured corporate environment Gerstner encourages everyone to call him Lou and to be candid with him. He is known to be blunt and intimidating with high-level staff, easy-going and likable with the corporate hoi polloi. He has been described by one colleague as having a technique modeled after the TV detective Columbo. "He'll say, 'Help me with this—it just doesn't make sense that...' It's effective because it gets people talking."

His style is not all sweetness and light. "If you are success- ful, Lou is with you," said Jerry Welsh, a consultant who worked for Gerstner in the American Express credit-card division. "If you flag or fail, he will pull the plug....And if IBM thinks they're getting a buttoned-down guy, they're wrong. Lou is someone who promotes china breakers, people with ideas that are unconventional for IBM." Gerstner himself has said he plans to create a cadre of 5,000 such china breakers—he calls them "Gerstner's guerillas"—and to ask each of them to enlist five more people. These in turn are to sign on more disciples until the entire company consists of corporate china breakers.

Gerstner already appears to have made certain that most of the former IBM old-boy network is gone. One former IBM executive who was an Akers confidante but who has also worked with Gerstner puts it this way: "The CEO's office is no longer a place for exchanging stories about the past. The thread that wove a great many of us together has been broken. Gerstner has no time for small talk or social amenities. When he asks you questions and you reply, he looks at you and repeats: 'Got it. Got it.'"

If 1993 is any barometer, Gerstner's new style and strategy are working, albeit modestly. In January, IBM reported its first quarterly profit in more than a year: $382 million. For all of 1993, however, IBM lost $8.1 billion, the most red ink in American corporate history. The stock price climbed more than nine points in 1993, but at 60 it's still sickly compared to its once robust 175.

Gerstner also received a kind of blessing from the late Thomas J. Watson Jr., son of IBM's founder and the man who directed the company's enormous growth in the late sixties and early seventies. Shortly before he died last December, Watson said he was "impressed" and "very optimistic" about the company's future under Gerstner's leadership. (Watson and Gerstner, incidentally, were neighbors in Greenwich Connecticut, where Gerstner lives with wife Robin and two college-age children).

Ultimately, though, it does not matter what Watson or any other IBM stalwart thinks of the man. Nor does it matter how successful Gerstner has been in his career up to now. What matters is the company's awesome, global bottom line. "This is a very big gamble for Gerstner," says Christopher Hunt, editor of Executive Search Review in Greenwich, Connecticut. "If he fails at IBM, he'll be remembered for that and nothing else."

"I remember playing a lot of beer-pong doubles with him." says a Kappa Sig brother.

Before it can dance it must lose some weight-and, while it's at it, learn a new tune.

Woody Klein, a former editor of IBM's Think magazine, served thecompany as a communications executive for 24 years. He retired fromIBM in 1992 and is now editor of The Westport News, a twice-weeklynewspaper in Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

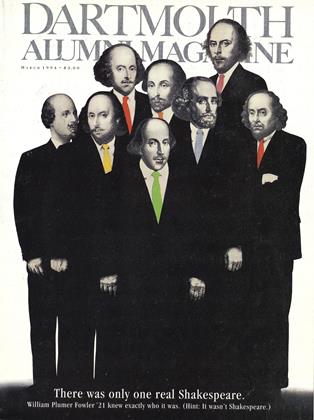

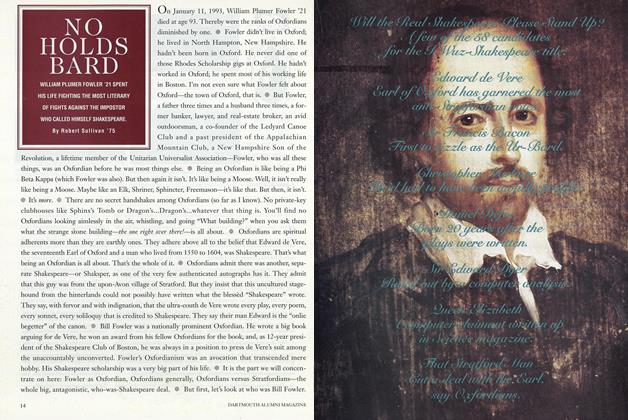

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

March 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

March 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

March 1994 By W. Blake Winchell -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

March 1994 By Christopher K. Onken -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

March 1994 By Morton Kondracke

Woody Klein '51

Features

-

Feature

Feature1960: Big, Bright, Lots of Them

October 1956 -

Feature

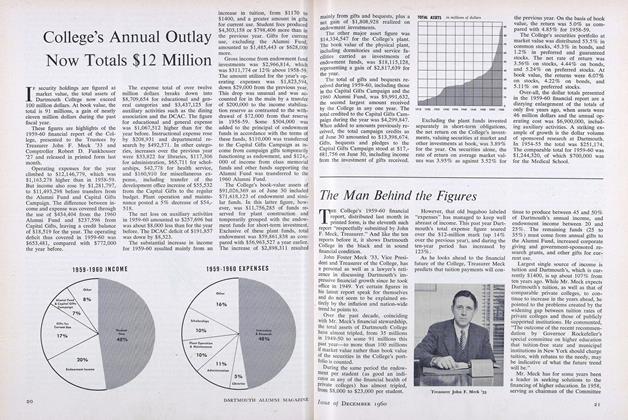

FeatureCollege's Annual Outlay Now Totals $12 Million

December 1960 -

Cover Story

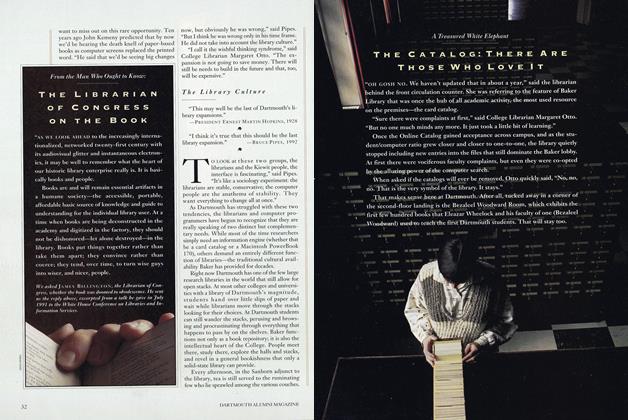

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Millennial Mindset

Mar/Apr 2011 -

Feature

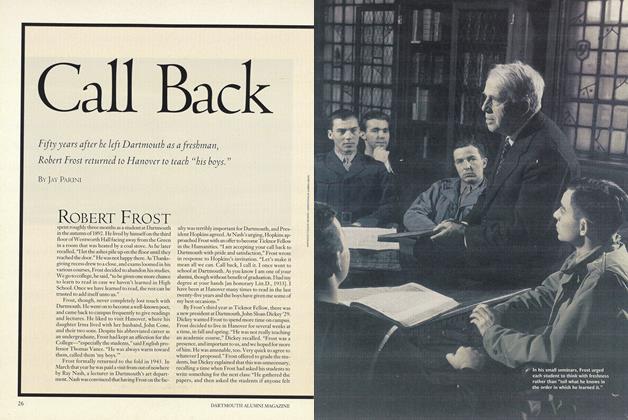

FeatureCall Back

May 1998 By Jay Parini -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY