Divers Notes & Observations

AS WE STOOD IN THE PARKING lot back of the White Church at 7:28 a.m. on Saturday, September 9, trying to figure out when to start our personal countdown, a cluster of explosions cracked out, sounding much like the shots that you hear on every final Fourth of July fireworks display. At once the eightstory Faulkner House, the largest remaining part of the old Dartmouth-Hitchcock Hospital, grandly caved in upon itself, as in a slow-motion film, in a mist of gray-white dust. (Almost for when the dust had cleared, a section of the northwest corner stood untouched. We were told that one of the cables strung between opposite walls, to insure that in falling they also pulled each other down, had broken. A crane and wrecking ball are now completing the demolition.)

We sensed a mix of reactions in the crowd around us. Sadness: "I was born there; my kids were born there." Disbelief: despite the well-publicized word that it would have been far more costly to refit the building to serve another College need than to destroy it, we still heard, "It certainly seems a needless waste of a good building." But walking back to our car past the Dragon Tomb, we noted four officiallooking characters speculatively looking up at Bradley as if to say, "How long before it's your turn?"

Our own dejection lasted until we reached the golf course, when on the first, second, and third holes it was difficult to concentrate over the strains of "The Salty Dog Rag" wafting from the Outing Club House. Buses were unloading backpacked freshpersons who must have called for just one more encore of the D.O.C. trips' national anthem.

Among the graffiti that cover the panels of the eight-foot green plywood fence still surrounding the hospital wreckage is the cryptic statement: "Without chemicals, life as we know it would not be possible." This might have been a premonition of the appearance of Dartmouth's 226th Convocation speaker, the much-honored organic chemist K. Barry Sharpless '63. The band had almost run out of flourishes when Convocation's faculty procession began, about ten minutes late, and we half-expected them to be triumphantly bearing signs "We're Number One!" more about that in a moment. As is his wont, President Freedman used plots and characters from current novels to make his point: this time, how life's random unfairnesses can be best avoided by the pursuit of idealism and an idealist mentor. Student Assembly President (and tennis captain) Jim Rich '96 prefaced his talk with a tribute to his late classmate and fellow athlete Sarah Devens '96; and then warned the '99s, after all the intense commitment to studies and extra-curricular activities that had brought them to Dartmouth, not to join "Team Nothing" the apathetic minority that fails to take advantage of all the riches the College offers.

Barry Sharpless, in what he called "his own private homecoming," proved that you don't have to be an accomplished speaker to make a great speech. Although he admitted "what lam really good at is understanding and controlling small molecules," his use of the Dartmouth idiom in recounting his own experiences at the College immediately won the entire Leede Arena's approval. He excerpted some of the wisdom of John Dickey's 1963 convocation talk to illustrate how the calamity of a failing English paper early in his freshman year pointed him toward his present distinction.

ANOTHER CALLING, ANOTHER prominent alumnus: Dinesh d'Souza '83, whose book, The End of Racism, is one of several currently stirring up the cauldron of affirmative action. D'Souza's octane level is somewhat lower than it was during his undergrad days on The Review. Despite its unavoidable litany of all the time-worn arguments of affirmative action's detractors, the book makes it clear that "equality of rights for individuals and equality of results for groups," though in conflict, are both desirable goals for society. Thus it is the duty of society, not just of government, to help level the playing field for that conflict. Racism, d'Souza says, is less part of the problem than is the socioeconomic handicap that besets discrimination's "victims."

A recent New York Times article reports that an apparently drunken man confronted a Sikh physician on a bus, shouted racist obscenities, and emptied a gun into him. After surgery at Bellevue, the doctor was in critical but stable condition. The name of the doctor's wife accompanying him was what caught our eye: Harmeet Dhillon '89, now a New York attorney, and one of Dinesh d'Souza's oftembattled successors as editor of the Review.

Another Times story notes that "at Dartmouth, which in 1972 became the next-to-last Ivy League school to go coed, the majority of the students in the class of '99 are women." Anything to upset the old grads, eh? That majority is, at last count, a big three, out of 1,048.

It may be that in celebration of the 50/50 milestone, however, Rockefeller Center's opening fall lecturer was ABC reporter Lynn Sherr, and her subject "Susan B. Anthony: Paving the Way for Women's Suffrage."

And, to keep us oldtimers au courant (that's French) on the appearance of its photographer here a couple of months ago, Playboy's issue featuring "Women of the Ivy League," is on the stands, and includes two notvery-revealing shots of a senior and a junior. Sales at the bookstore, normally three copies a week, jumped at once to 12.

U.S. NEWS WINS THE MEDIA gonfalon this month, though. In its annual guide to America's Best Colleges, Dartmouth rose a notch to seventh place, tied with Caltech. But in a new ranking, schools "where the faculty has an unusually strong commitment to undergraduate teaching," the Green comes in ahead of everybody. (How the magazine figures out these various ratings is only slightly more complicated than how the annual NFL wild-card Super Bowl candidates are determined). On the Times's Sunday op-ed page (we do read other publications) a Harvard and a Northwestern professor ask, "Why did it take so long? Why is teaching treated as an appendix in evaluating educational institutions?" They suggest that teachers are at least as valuable as quarterbacks in the competition among colleges and universities for recruitment. But the two profs lament that competition ceases when it comes to one college's desire to steal away another's top teachers. Nor can they suggest how quality teaching could ever be assessed even if some market-driven Alma Mater suddenly wanted to do so.

On this last topic, we don't want to give any rival Ivy recruiters any ideas but for the third time in three years, a Dartmouth faculty member has received President Clinton's Presidential Faculty Fellow Award, one of fifteen American scientists so honored. He is assistant professor of mathematics Daniel Rockmore, whose work is what he calls group theory, a special branch of the subject that utilizes mathematical symmetry to understand data uncovered in nature and such pursuits as music, design, and engineering. Probably not coincidentally, the College has also announced the receipt of a $4 million award from the National Science Foundation, to enable the math department to foster much the same objectives: making mathematics both more interesting and more useful to students by relating it to the principles of the world around them.

NOT IN THIS WORLD IS THERE a more delightful diva than the renowned mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade, who packed Spaulding Auditorium in September. Expressive, winsome, tragic, mocking, jocular, her voice matched each of the moods of a repertory that flew from Scarlatti to William Bolcom. One Aaron Copland piece, text by Emily Dickinson, "Why Do They Shut Me Out of Heaven," she dedicated to her high-school-age daughter, and brought the house down when she twice delivered the last word in the title as "Dartmouth." She and her dexterous accompanist Martin Katz could still be giving encores.

THE BIG GREEN OPENED ITS football season this year with not one but two games the first half against Penn, and the second half. First, 12-3; second, 0-17. For 30 minutes the team looked very unlike the cellar-dwellers the experts had predicted. Sparked by quarterback Ren Riley '96 and a bucketful of potential standouts on defense, they stood up to the Ivy champ Quakers, but the tide-turner was Penn's all-Ivy wide receiver Miles Macik, who made 12 catches for 158 yards and two touchdowns. A more pleasant Saturday afternoon was September 23 rd, when the Green vanquished the Fordham Rams 34-14, in a game that featured more turnovers than the Pepperidge Farm pantry.

With six letterwomen returning, field hockey, second in the league last year, looks forward to another big season. The team has already topped Maine, 2-1, in revenge for the Bears' victory over Dartmouth in last year's ECAC championship. Women's soccer, ranked 19th nationally, started the season with three wins, over U. of Michigan, U. of Texas, and UNH. Men's soccer will be no doormat, even though seven of last year's starters graduated, two more got injured during pre-season, and midfielder Methembe Ndlovu '97 is out for the first five games while he helps his homeland Zimbabwe team try to qualify for the Olympics.

One other sports item: Ann Kakela '92, daughter of Dartmouth footballer Wayne '57, strokes bow oar on the U.S. national crew. She and her teammates won a gold medal at the World Rowing Championships in Tampere, Finland.

The College once frowned on students spending late post-study or post-party hours at Harry's Track Stop in Lebanon for, we suppose, all the usual reasons. Perhaps they will now relent. There's a sign over the gas pumps: "Premium Diesel With Patented Lubricity Remover."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

November 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

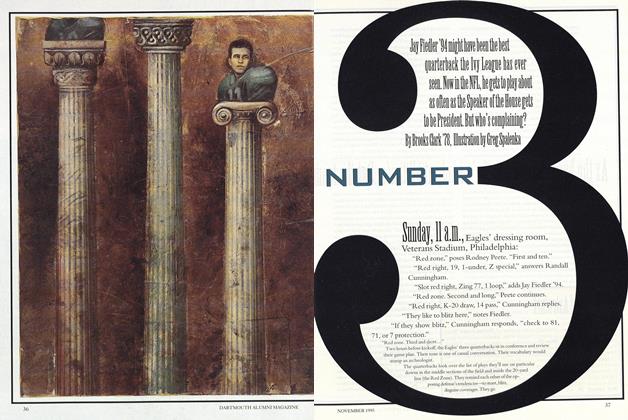

FeatureNUMBER 3

November 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

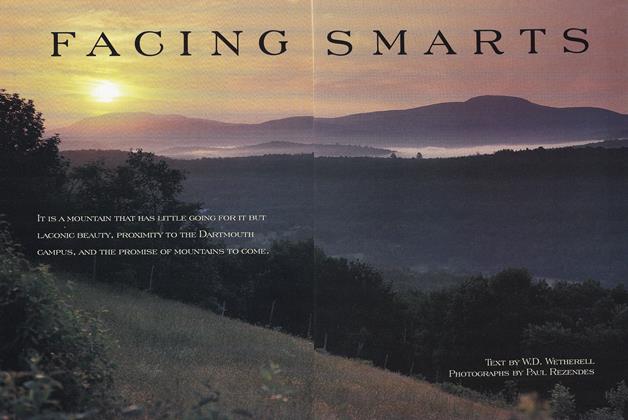

Cover StoryFACING SMARTS

November 1995 By W.D.Wetherell -

Feature

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

November 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureSentimental Sap

November 1995 By Robert K. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleFull Cycle

November 1995 By Woody Klein '51

"E. Wheelock"

-

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

MARCH 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

December 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

MARCH 1995 By "E. Wheelock"

Article

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL FALL MEETING OF TRUSTEE BOARD

December, 1925 -

Article

ArticleYALE DORMITORY NAMED FOR WHEELOCK

MAY, 1928 -

Article

ArticleGerry Memorial Hall

March 1962 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

Nov/Dec 2010 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

January 1961 By Russ STEARNS CE'38 -

Article

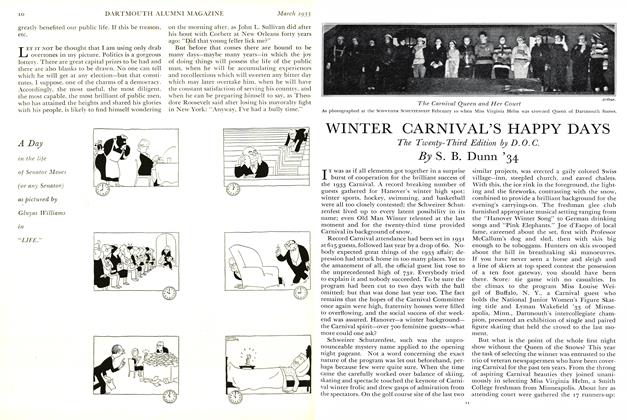

ArticleWINTER CARNIVAL'S HAPPY DAYS

March 1933 By S. B. Dunn '34