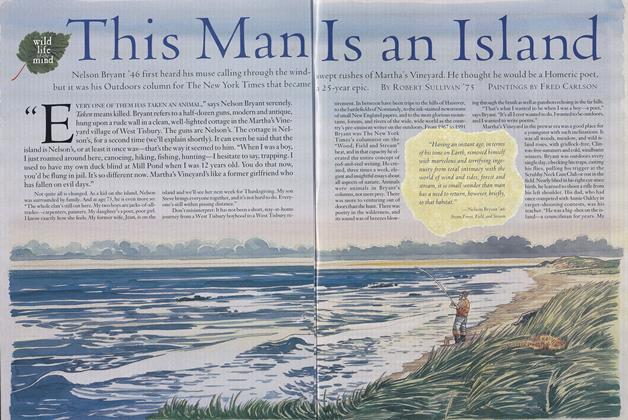

The man who runs Shinnecock Hills is more than groundskeeper, HE IS KEEPER OF AN ANCIENT FLAME.

TODAY IT'S THE GUY FROM TIME.

Yesterday it was the Times. The day before, the nightly news. Day before that, the photographer from Time." Good Morning America"? Been there. The national news? Done that. Today, Time magazine. No sweat.

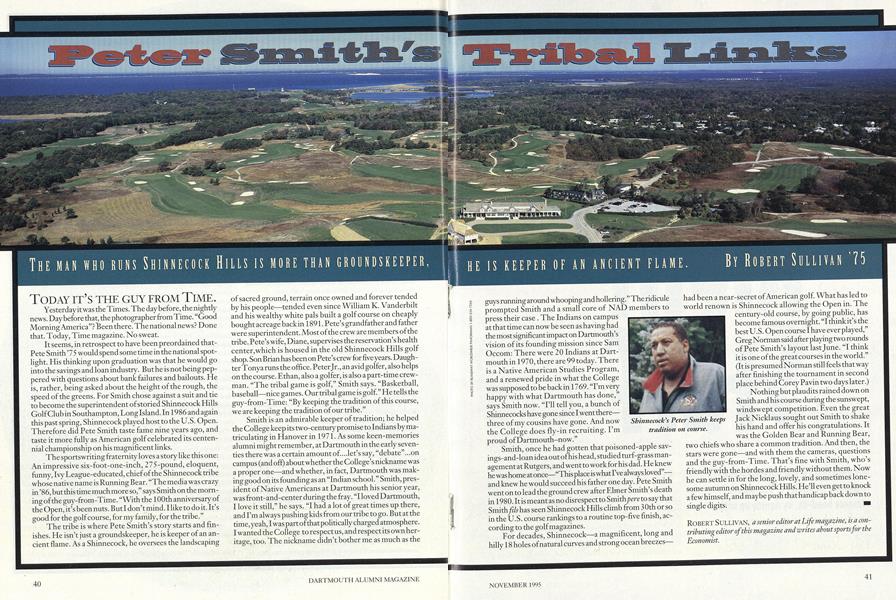

It seems, in retrospect to have been preordained that Pete Smith '75 would spend some time in the national spotlight. His thinking upon graduation was that he would go into the savings and loan industry. But he is not being peppered with questions about bank failures and bailouts. He is, rather, being asked about the height of the rough, the speed of the greens. For Smith chose against a suit and tie to become the superintendent of storied Shinnecock Hills Golf Club in Southampton, Long Island. In 1986 and again this past spring, Shinnecock played host to the U.S. Open. Therefore did Pete Smith taste fame nine years ago, and taste it more fully as American golf celebrated its centennial championship on his magnificent links.

The sports writing fraternity loves a story like this one: An impressive six-foot-one-inch, 275-pound, eloquent, fanny, Ivy League-educated, chief of the Shinnecock tribe whose native name is Running Bear. "The media was crazy in '86, but this time much more so," says Smith on the morning of the guy-from-Time. "With the 100th anniversary of the Open, it's been nuts. But I don't mind. I like to do it. It's good for the golf course, for my family, for the tribe."

The tribe is where Pete Smith's story starts and finishes. He isn't just a groundskeeper, he is keeper of an ancient flame. As a Shinnecock, he oversees the landscaping of sacred ground, terrain once owned and forever tended by his people tended even since William K. Vanderbilt and his wealthy white pals built a golf course on cheaply bought acreage backin 1891. Pete's grandfather and father were superintendent. Most of the crew are members of the tribe. Pete's wife, Diane, supervises the reservation's health center,which is housed in the old Shinnecock Hills golf shop. Son Brian has been on Pete's crew for five years. Daughter Tonya runs the office. Peter Jr., an avid golfer, also helps on the course. Ethan, also a golfer, is also a part-time crewman. "The tribal game is golf," Smith says. "Basketball, baseball—nice games. Our tribal game is golf." He tells the guy-from-Time: "By keeping the tradition of this course, we are keeping the tradition of our tribe."

Smith is an admirable keeper of tradition; he helped the College keep its two-century promise to Indians by matriculating in Hanover in 1971. As some keen-memories alumni might remember, at Dartmouth in the early seventies there was a certain amount of.... let's say," debate"... on campus (and oft) about whether the College's nickname was a proper one and whether, in fact, Dartmouth was making good on its founding as an "Indian school." Smith, president of Native Americans at Dartmouth his senior year, was front-and-center during the fray. "I loved Dartmouth, I love it still," he says. "I had a lot of great times up there, and I'm always pushing kids from our tribe to go. But at the time, yeah, I was part of that politically charged atmosphere. I wanted the College to respectus, and respectits own heritage, too. The nickname didn't bother me as much as the guys running around whooping and hollering. prompted Smith and a small core of NAD members to press their case . The Indians on campus at that time can now be seen as having had die most significant impact on Dartmouth's vision of its founding mission since Sam Occom: There were 20 Indians at Dartmouth in 1970, there are 99 today. There is a Native American Studies Program, and a renewed pride in what the College was supposed to be backin 1769. "I'm very happy with what Dartmouth has done," says Smith now. "I'll tell you, a bunch of Shinnecocks have gone since I went there three of my cousins have gone. And now the College does fly-in recruiting. I'm proud of Dartmouth-now."

Smith, once he had gotten that poisoned-apple savings-and-loan idea out of his head, studied turf-grass management at Rutgers, and went to work for his dad. He knew he was home at once "This place is what I've always loved and knew he would succeed his father one day. Pete Smith went on to lead the ground crew after Elmer Smith's death in 1980. It is meant as no disrespect to to say that Smith fils has seen ShinnecockHills climb from 30th or so in the U.S. course rankings to a routine top-five finish, according to the golf magazines.

For decades, Shinnecock a magnificent, long and hilly 18 holes of natural curves and strong ocean breezes had been a near-secret of American golf. What has led to world renown is Shinnecock allowing the Open in. The century-old course, by going public, has become famous overnight. "I think it's the best U.S. Open course I have ever played," Greg Norman said after playing two rounds of Pete Smith's layout last June. "I think it is one of the great courses in the world." (It is presumed Norman still feels that way after finishing the tournament in second place behind Corey Pavin two days later.)

Nothing but plaudits rained down on Smith and his course during the sunswept, windswept competition. Even the great Jack Nicklaus sought out Smith to shake his hand and offer his congratulations. It was the Golden Bear and Running Bear, two chiefs who share a common tradition. And then, the stars were gone and with them the cameras, questions and the guy-from-Time. That's fine with Smith, who s friendly with the hordes and friendly without them. Now he can settle in for the long, lovely, and sometimes lonesome autumn on ShinnecockHills. He'll even get to knock a few himself, and maybe push that handicap back down to single digits. "

Shinnecock's Peter Smith keeps tradition on course.

ROBERT SULLIVAN, a senior editor at Life magazine, is a contributing editor of this magazine and writes about sports for the Economist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

November 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureNUMBER 3

November 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

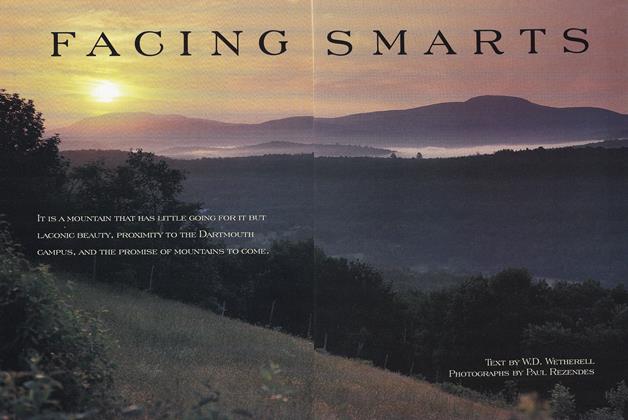

Cover StoryFACING SMARTS

November 1995 By W.D.Wetherell -

Feature

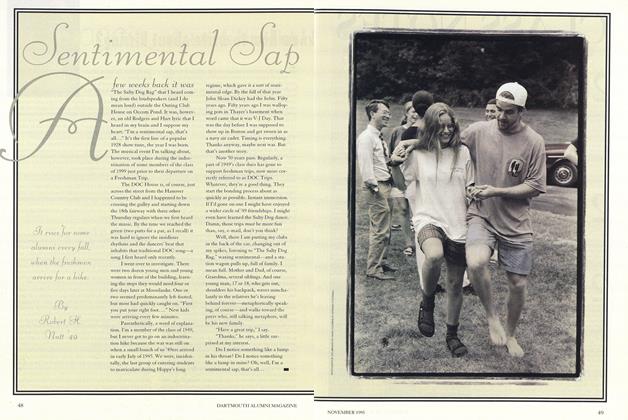

FeatureSentimental Sap

November 1995 By Robert K. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleFull Cycle

November 1995 By Woody Klein '51

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Sports

SportsAt the Winter Games

April 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Trophy Finally Stays Put

February 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleAn Evening with Rassias

May 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Article

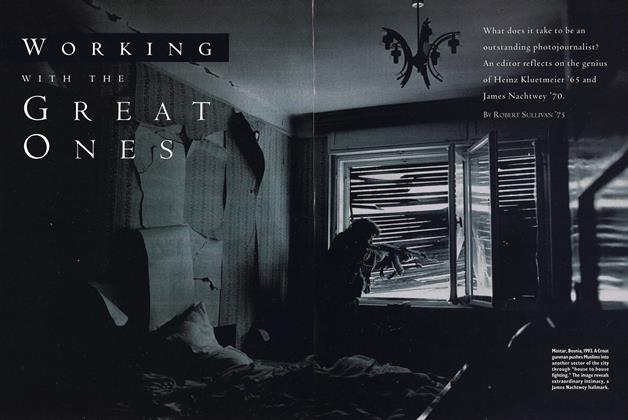

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

JUNE 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJanette Lorraine Cupp '79

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

NOVEMBER 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

DECEMBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Peace Corps at 25

APRIL 1986 By Laura T. Hammel -

Feature

FeatureNATIONAL SECURITY: Issues and Prospects

December 1960 By LOUIS MORTON -

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan