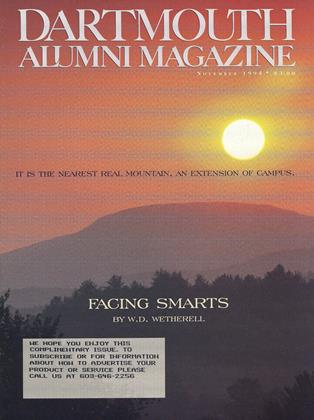

Name a New Hampshire mountain that is not named after a President, commemorates no Indian chief, does not rise above 4,000 feet, is of little interest to peak baggers, illustrates no calendar (at least none I've ever seen), is not mentioned by Robert Frost, holds no meteorological records, is not carved into ski trails or littered with condominiums, would provide no views whatsoever if not for the disused fire tower on its top, is not one. of the two most frequently climbed mountains in the world, has little or nothing of the dramatic about it at all, and yet in its laconic no-frills kind of fashion has provided generations of mountain lovers and hikers with refreshing solitude, satisfactory steepness, and thanks to that fire tower world-class views.

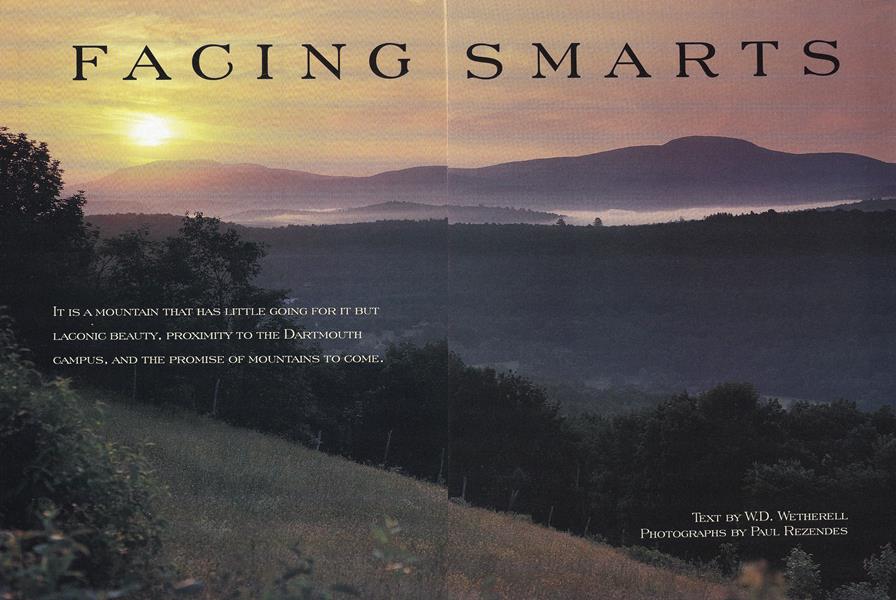

Need more help? By a happy conjunction, a fortunate twist of a highway engineer's pen, the most frequently obtained view of this mountain is by all odds the best. The view, that is, gained by anyone driving north out of Hanover on Route 10, where the road curves eastward for a moment just before dropping down the steep decline past the Chieftain Motel. There out the windshield in the distance, unavoidable, immediately compelling: a mountain, its size magnified by the suddenness of its appearance, magnified even more in winter under new snow, looking—to compare fair things to foul like a long blocky billboard thrown against the sky advertising Mountains Ahead! Everywhere! Mountains Galore! The view—and then the fast exhilarating drop down the hill, as if the road were a slide launching you north toward the mountain and the rugged country that lies beyond.

It must be obvious now to anyone who has spent much time in this part of the world that the mountain referred to here is Smarts Mountain, all 3,238 proud feet of it, the mountain that rises above Lyme and gives what would otherwise be a gentle valley town its hard wild backbone in the east. High enough to generate its own weather, fringed near the top with a wind-bent band of boreal spruce, graced but not cluttered with trails, haunted with cellar holes and old walls, Smarts has a surprisingly large fan club, drawing its members not only from generations of Dartmouth students but from the citizens of Lyme, those who hike it, and those lucky enough with topography to have an unobstructed view of its summit from their homes.

I'm in this last group, solidly. If I take my eyes off this typewriter between sentences, I can glance out the window to my right and see Smarts in profile, the long domed summit rising above lower Lambert Ridge. In March from this angle the sun rises directly above the summit, making it seem as if some prehistoric and vanished race through unimaginable labor erected the mountain to mark off the equinox, give the returning sunlight an axle on which to spin. Now, writing in May, the sun rises a good 20 degrees to its north but still manages to illumine the summit before coloring anything lower. It's the first thing I see in the morning, the first fact that registers, the undeniable bulk of it slapping me awake in a way the morning news, the first cup of coffee, can't even begin to equal. How fares it with Smarts this morning? What lenticular cloud smudges and enlarges its silhouette? What birds soar across it? What will the morning light do to its shape?

Its shape? I happen to love it, but honesty compels me to admit that shape is not Smarts's aesthetic strong point. No perfect cone here like Chocorua's, not even the rectangular symmetry of neighboring Mt. Cube. The terms that come to mind in describing Smarts's silhouette tend toward embarrassing rhymes: lump/bump/rump/hump. It's all these, and yet, after you know it for a while, the long anticlinal line tends to become softer, more fluid, suggesting the flattened breast of a reclining Modigliani nude, or, in summer, a green whale breaching northward through the mist.

And then there's that business about its name. Mr. Smarts was a trapper here in the old days before the town was settled. Being down on his luck and/or of avaricious disposition, he took to stealing pelts from Indian traps, clumsily, since the Indians caught him and drowned him under the ice in Reservoir Pond at the mountain's base. Even the Lyme town history is a bit apologetic in explaining this having the town's most prominent feature immortalize a poacher! But there's something about the name that fits. The fact it overlooks an institution of higher learning and all the smarts therein contained. The fact it seems, in the serene way of mountains, to know something we don't. Smarts indeed, smarter than any of us, and I've even seen it on winter days when the setting sun hits the icy fire tower just so wink.

TO ANYONE lucky enough to know a mountain not only from the distance but, in TV-speak, "up close and personal," its slopes will always loom in double focus, seen both from the distance in silhouette and from the inside looking out. In time, the seeing merges into one stereoscopic whole. No view so coolly distant it doesn't remember the tug of gravity as you struggled up its side; no hike so tough, no immersion so deep, it doesn't include the detachment and wonder that comes with drawing back.

So closer now, in tight up one of Smarts's trails. Lots of memories here, lots of fine moments. I think of the Columbus Day my wife and I guided my sister-in-law up the Clark Pond Trail, the old Appalachian Trailhow this city girl on her first climb did just fine, thank you, and was rewarded on top by a fresh snowfall, so, to her eyes, the summit loomed high as Everest. How earlier that fall I tried bushwhacking up the mountain's conspicuous V-shaped notch (a notch down which loggers of an earlier day liked to roll freshly cut trees) how, in following a rapidly diminishing Grant Brook to its source on the slide, I got caught in a sudden blizzard that plastered me to the mountain, not only with snow but with red and orange maple leaves. How many hours I've spent trying to find Grant Brook's tiny and elusive trout. How, in trying to schuss down the Ranger Trail one February afternoon, I flew breathless down the side, only to hit a mogul that drove my ski pole and the hand that held it into my jaw, knocking me flat.

And then there's the fire tower, the views that seem so expansive for the very lack of them until you climb the metal stairway and shove open the trap door to its glass-enclosed (and DOC-maintained) top. Mt. Washington, of course, king of pyramids; Reservoir Pond with its fringe of silver beaver ponds; the pastoral view toward the Connecticut and a landscape that always seems two shades greener than any to the east; Ascutney prominent in the south; Killington, the gentle synclines and anticlines of the distant Greens. Even my own house, its miniaturized roof anyway, directly west at the conjunction of two fields.

One September day I climbed the summit only to find it socked in with clouds. Four hikers were huddled inside the fire tower, Dartmouth freshmen on their fall orientation. We ate our sandwiches in silence, waiting for gaps in the clouds to provide the now-you-see-it, now-you-don't views that were the best we could hope for. One of the students was from Switzerland, and I noticed him looking rather dubiously at the sandwich that was handed him by his neighbor out of a large red pack.

"What's the matter?" he was asked. "Haven't you ever seen a peanut butter sandwich before?"

"Good," he pronounced.

And with that we all cheered.

HERE at the end let me pull back again, have you look with me out this window at Smarts rising in the east. A cold front has just pushed in, driving those dark and beautiful cumulus out ahead of it to scour the sky clean. Smarts is colored with their shadow, actually blackened, and with the trick of light that plays over hills seems higher than usual, steeper, more remote. Geologists tell us these New Hampshire hills are the remnants of mountains that in antediluvian times loomed much higher, and on days like this one Smarts still has something of that earlier aura, a giant reduced to human scale yet able in magic moments to resume his prior height, bulk, and distinction.

Clouds, darkness and then both are split apart by an opportunistic wedge of sun, the mountain brightens, the ridges take on dimension and depth. A transformation this sudden calls for a drum roll, organ music, a brassy fanfare for the common and not-so-common mountain. Smarts forever! Smarts triumphant! A mountain just high enough to shape the sky.

IT IS A MOUNTAIN THAT HAS LITTLE GOING FOR IT BUT LAGONIG BEAUTY, PROXIMITY TO THE DARTMOUTH CAMPUS, AND THE PROMISE OF MOUNTAINS TO GOME.

Grant Brook, left, offers tiny and elusive trout and a hidden origin high on the mountain's slopes. They loom over Reservoir Pond, right; the Outing Club has a cabin on its shore with one of the finest Smarts views, The photo on the preceding spread, shot from across the river in Norwich, is a sunrise.

A tiny spruce finds a niche in a crack of granite, above. At right, the view from Black Brook.

Bunchberry, below. Right: the view from Thetford Hill.

W. D. WETHERELL'S latest novel, The Wisest Man in America, was published last spring by the University Press of New England He is also the author of The Smithsonian Guide to the Natural Areas of Northern New England.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

November 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureNUMBER 3

November 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

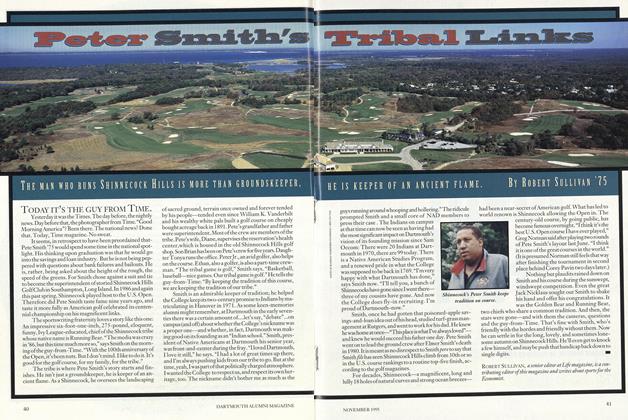

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

November 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureSentimental Sap

November 1995 By Robert K. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleFull Cycle

November 1995 By Woody Klein '51