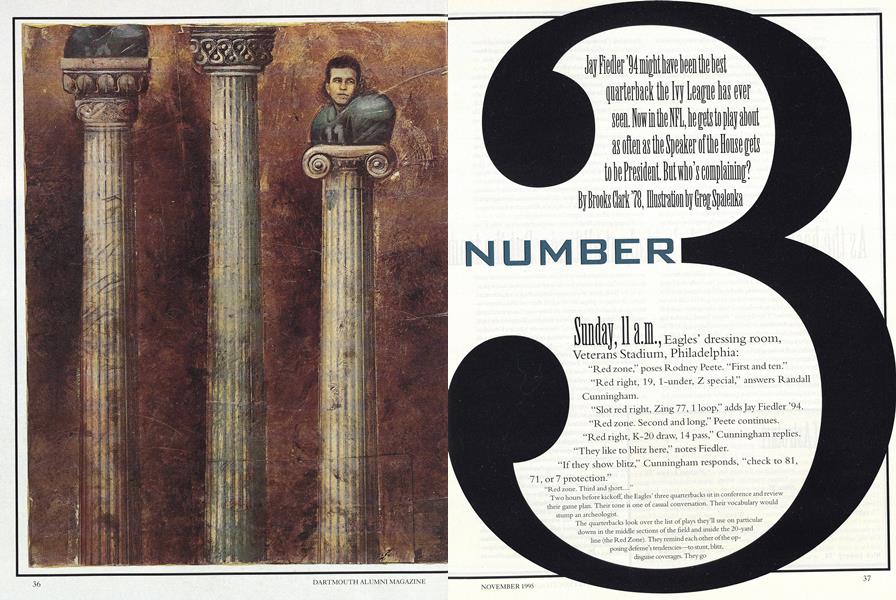

Jay Fiedler '94 might have been the best quarterback the Ivy League has ever seen. Now in the NFL, he gets to play about as often as the Speaker of the House gets to be President. But who's complaining? By Brooks Clark '78, Illustration by Greg Spalenka

Sunday, 11 a.m., Eagles' dressing room, Veterans Stadium, Philadelphia: * "Red zone," poses Rodney Peete. "First and ten." "Red right, 19, 1-under, Z special," answers Randall Cunningham. "Slot red right, Zing 77, 1 loop," adds Jay Fiedler '94. "Red zone. Second and long," Peete continues. "Red right, K-20 draw, 14 pass," Cunningham replies. "They like to blitz here," notes Fiedler. "If they show blitz," Cunningham responds, check to 81, 71, or 7 protection."

"Red zone. Third and short.... Two hours before kickoff, the Eagles' three quarterbacks sit in conference and review their game plan. Their tone is one of casual conversation. Their vocabulary would stump an archeologist.

The quarterbacks look over the list of plays they'll use on particular downs in the middle sections of the field and inside the 20-yard line (the Red Zone). They remind each other of the opposing defense's tendencies to stunt, blitz, disguise coverages. They go over the plays they'll cheek off to at the line when they see a blitz or a stunt coming.

A few minutes later, they tape up, get dressed, and head out to the Astro Turffor warmups. Cunningham and Peete throw to receivers. Fiedler tosses to backs, tight ends, and defensive backs. After the coaches' final words in the locker room and introductions over the P.A., it's kickoff time, which for Fiedler means the sidelines. "Once the game starts," says Fiedler, "the baseball cap goes on and the clipboard comes out."

Jay Fiedler occupies a spot in the NFL known as No. 3. This is the quarterback who actually gets to play quarterback about as often as the Speaker of the House gets to be President. It's a curious spot on the food chain—somewhere between Earl Morrall and the Maytag repairman, generally closer to the latter. As the backup's backup, he's ready at all times. But the team hopes it never has to turn to him. In other words, when things go according to plan, he's the most invisible man in the NFL.

Before this year's Super Bowl, the wits at Miller Lite put together a wicked NFL films parody complete with Wagnerian soundtrack and You-Are-There narrator describing an unused gridiron gladiator who'd been the under-understudy at every single Super Bowl. The satirists may have gotten their inspiration from Gale Gilbert, who was on the sidelines for four Super Bowl defeats as No. 3 to Buffalo's Jim Kelly and Frank Reich, then, by an incredible stroke of fate, signed as a free agent with San Diego and ended up playing third QB for his fifth Super Loss in a row behind Stan Humphries and Jeff Brohm. (Jeff Brohm? If we'd typed "Norm Snead" in that last space, few of us would know the difference. Now, quick: Who is Elvis Grbac? As we're discussing the place of No. 3 QBs in the Elizabethan Chain of Being, it might be instructive to note that Brohm and Grbac are No. 25.)

Enlightened teams often use the No. 3 spot to give a longshot from a small or brainy school a chance to overcome his lack of spring practice and develop into the next Dave Krieg. This accounts for Ivy Leaguers like John Witkowski (Columbia '83), who played for the Detroit Lions for several seasons; Jason Garrett (Princeton '89), who started and won a game for Dallas last Thanksgiving Day, when Troy Aikman and Peete (then a Cowboy) were both out of commission; and Dartmouth's own Jeff Kemp '81, who spent 11 years in the pros, including one with Philadelphia.

Often No. 3s are appreciated for the good cheer they bring to their role. Joining the Redskins after years as a starter in Canada, Joe Theismann wanted to get into the game so badly that he volunteered to return punts. He was so pushy, in fact, that Sonny Jurgensen and Billy Kilmer made a pact to put aside their own rivalry for the greater goal of keeping Theismann off the field.

Fiedler—a second cousin twice removed of Arthur Fiedlerwas equally eager to play third fiddle for the Eagles last year. One reason was the chance to play behind Randall Cunningham, one of the more remarkable quarterbacks of his generation. "It's exciting watching him play," says Fiedler. "He does things with a football that not too many people can do." And Fiedler learned from Bubby Bnster, a product of the bayous of Louisiana in his ninth year in the league. (Blister became a free agent this season and left for the New York Jets and Peete, the former number two at Dallas, was signed to take his place.)

During games, Fiedler's job is to chart the plays. That is, he writes down which plays were run and how many yards they gained. In our reverence for the sophistication and complexity of the NFL, most of us assume there's high science at work in the charting of plays. We imagine that a skillful chartmeister can detect subtle patterns of behavior, bring invaluable pockets of defensive vulnerability to light, and explose the mysteries of the big play. "Coach," we see the man with the clipboard and the baseball cap uttering ominously. "I think you ought to have a look at this."

"Good heavens, I think you're onto something!" the coach gasps like a professor in Tom Swift. "If we run Counter Crossbuck 22 to the right, there'll be nothing but Prescription Athletic Turf between us and a nifty six points! Quick! Let's try it!"

In reality, keeping the chart isn't exactly rocket science. The main use is at film time, to know which plays you're watching and which ones are coming up, so players can remember what was going on. Every now and then Fiedler or Brister might notice something—a coverage they could exploit or a play that might work—and pass it along.

Fiedler does get to play quarterback as wellsomebody else's quarterback. Like a mock debater prepping a Presidential candidate, the No. 3 pretends he's the opposition during the week's practices. He rolls out left to imitate southpaw Steve Young. As an erstatz Troy Aikman, he scrambles only to the right. He even imitates fellow youngsters Heath Shuler and Gus Frerotte, who at different times have started for the Redskins. The closest Fiedler himself got to the action last year was the final two games, when Brister started and Jay was waiting on deck, one anterior cruciate ligament away from the hotseat.

In another moment in football history, a No. 3 quarterback might not have a realistic expectation of ever as- cending. If a guy didn't beat out the top draft picks this year, goes the reasoning, why would he beat out next year's batch?

But we're approaching an interesting time in NFL quarterbacking. Gall it the result of chaos in the league, an example of short-term planning, or a haunting parallel to our vacuum of national leadership but the NFL appears to be facing a quarterback shortage. Some all-timers, like Joe Montana and Warren Moon, are exiting, and the incredible class of'83—John Elway, Boomer Esiason, Jim Kelly, Dan Marino isn't too far behind. There are several young superstars, notably Troy Aikman, Steve Young, and Steve Bono. But after them there's a dropoff (sorry, Drew Bledsoe), where the hot rookies of yesterday are having a tough time developing into the superstars of tomorrow. One theory is that with free agency and the salary cap, teams aren't able to invest the time it takes to groom NFL quarterbacks. And when they do manage to groom them, the stars get injured or end up somewhere else. For example, Heath Shuler and Trent Dilfer, the top two quarterbacks drafted in '94, both had rookie seasons that would have made John Elway switch back to baseball. On top of all that, there's expansion, which will mean there are even more spots to be filled.

"It's a time for people like Jay to surface," proclaims Zeke Bratkowski, who was the Eagles' quarterbacks coach last year (and, typical of the mayhem in the league, moved with much of the Eagles' coaching staff to the New York Jets).

Fiedler knows what it's like to come up behind the older guys. He moved from running back to quarterback at age 8, in Pee Wee football, when his brother moved up to a higher league. His father, Ken, is the basketball coach at Springfield Gardens High in Queens; his mother, Donna, is an elementary school teacher in Far Rocka way. Jay won two New York State pentathlon titles at Long Island's Oceanside High. He had an incredible junior year as a quarterback but tore a posterior cruciate ligament in his left knee four days before his senior season, which scared the football powers away. Fiedler was recruited by Stanford, but as a decathlete. At Dartmouth he could compete in both football and the decathlon.

Big Greeners are still talking about the Princeton game in Fiedler's junior year, 1992, when he converted nine of 13 third downs, passed two touchdowns, and ran for two more to engineer a 34-20 victory that clinched Dartmouth's third straight Ivy title. For the season, Fiedler led all of Division I-AA in passing ef- ficiency and was projected by some pro scouts to be one of the top three quarterbacks coming out of the college ranks in 94.

Fiedler learned an important lesson in his senior season, when his completion percentage dropped from 64.1 to 50.3 and his interceptions rose from 13 to 25. He realized he was trying too hard to do everything himself. Finally Fiedler got himself back on track in another Princeton game the fans are still talking about. Trailing 22-8 in the fourth quarter, he proceeded to complete 13 of 20 passes for 224 yards and a 28-22 win. He ended his career with 6,684 yards an Ivy record and 56 touchdowns and a 21-7-1 record as a starter.

After his senior: season, Fiedler was invited to play in the East-West Shrine Game in San Francisco. After four days of coaching from Florida's Steve Spurrier, the Lee Strasberg of quarterback coaches, Fiedler turned in a dazzling performance that earned him a citation as co-Offensive Player of the Game. "That raised my stock considerably," says Fiedler. Gil Brandt, scouting guru of the Dallas Cowboys, notes: Ive never seen a player improve as much in four days as Fiedler did during that week. I told several coaches, 'When you get down to the fourth round or so, this is a guy you can work with for your future.'

Fiedler attended scouting combines in March and impressed the scouts with his size (six-two, 220 pounds), his decathlete's buffbod (he bench presses 325 and runs a 4.6 40), his brains (3.1.5 GPA as an engineering major), and his arm. Before the draft I came up to Dartmouth to work him out," says Bratkowski. "We were very impressed with his athletic ability. I'd seen a lot of tapes of him, and almost everything I could find out about him was good his athletic skill, intelligence. He was very coachable, very likeable."

Fiedler wasn't picked in the draft, but afterwards four teams called and offered him free-agent contracts. He chose Philadelphia, mostly because of the prospects for the future, with Cunningham entering his golden years and Brister headed tor free agency. And he realized that over the previous three years, the Eagles' No, 3 quarterback has started eight of 48 games. Fiedler did everything he: could to prepare for training camp. "He attended the mini-camps, the voluntary Camps, the rookie camps," says Bratkowski. "He took the time to work and talk, and he's a quick learner. He solidified his athletic skills in the preseason, then he got the opportunity to play in a preseason game, which gave us the chance to see him under pressure a little bit. He was able to evade and react to situations. He showed athletic skills and football intelligence. He has the intelligence to know where to go with the ball."

His first game was an exhibition against Chicago. Playing football in the NFL is something that each person has to experience for himself," says Fiedler. "But it didn't overwhelm me; it's just a football team. They re more athletic, faster, bigger, stronger." In all, Fiedler did well enough in practices and three preseason games (12 for 24 for 148 yards) to beat out Georgia's Preston Jones, the previous year's No. 3, for his spot on the roster. "I had mixed feelings that day, says Fiedler. Its hard to balance celebrating for yourself with feeling bad for someone else. I really respected Preston as a player. Maybe the fact that he alrady has a year under his belt and I have a lot of room for improvement was a big factor.

Last spring Fiedler wanted to get some playing time in the World Football League, the NFL's international expansion arm. But the Eagles had different ideas. They didn't want him to get hurt, for one thing. For another, they wanted him to keep working within their offensive system, which he did, by attending all six of the Eagles' offseason Fielder then proceeded to have a solid preseason completing eight for ten passes for 81 yards (no TDs, no interceptions) in three exhibition games and beating out a fourth-round draft pick, Dave Barr of Cal, for the number-three spot. "His future's up to him, really," says Bratkowski.

"My goal," says Fiedler, "is to just keep improving my stuff from year to year, and that's really all I can do."

As tie total's Mop, he's ready it all tines. M tie lea hopes it never has to turn to him.

BROOKS CLARK '78 is a freelance writer in Knoxville, Tennessee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

November 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

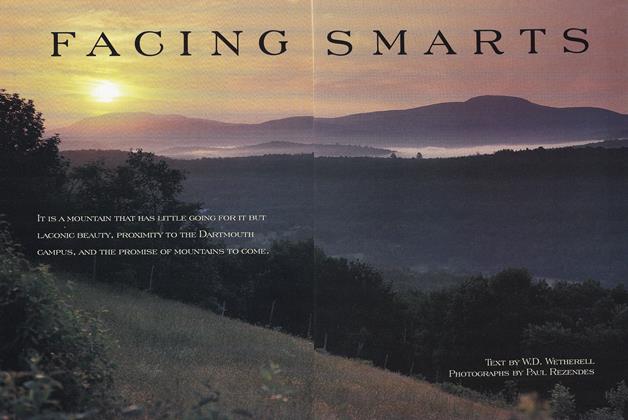

Cover StoryFACING SMARTS

November 1995 By W.D.Wetherell -

Feature

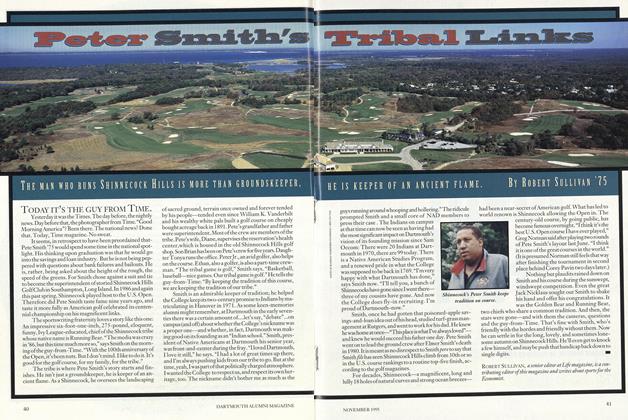

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

November 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

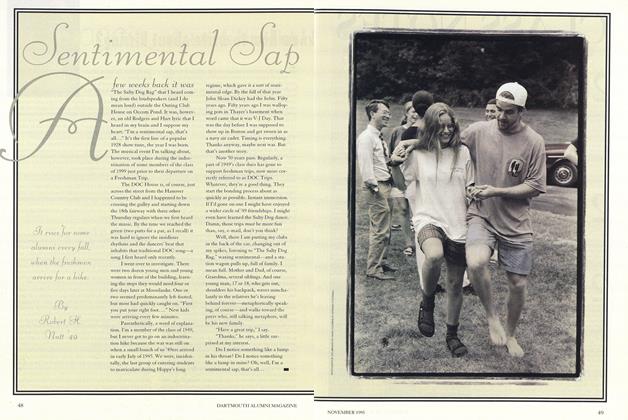

FeatureSentimental Sap

November 1995 By Robert K. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleFull Cycle

November 1995 By Woody Klein '51

Brooks Clark '78

-

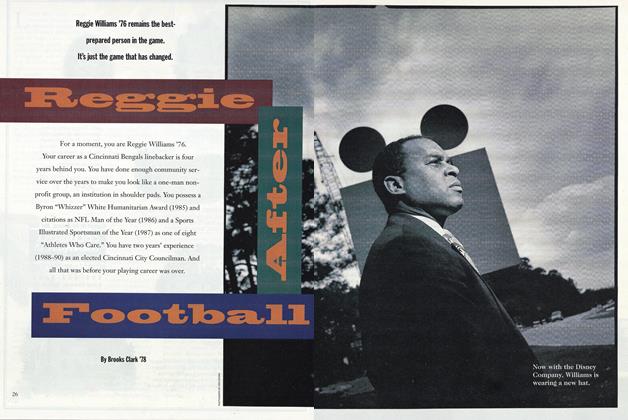

Cover Story

Cover StoryReggie After Football

May 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleThe Jump to Gotham

December 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPease Out There

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleMelissa McBean, Scoring Machine

October 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleFAMILY TIES

SEPTEMBER 1997 By BROOKS CLARK '78 -

Article

ArticleReservation for a Clinic

NOVEMBER 1997 By Brooks Clark '78

Features

-

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

MAY • 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCharles Wheelan '88

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1973

JULY 1973 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

MAY 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

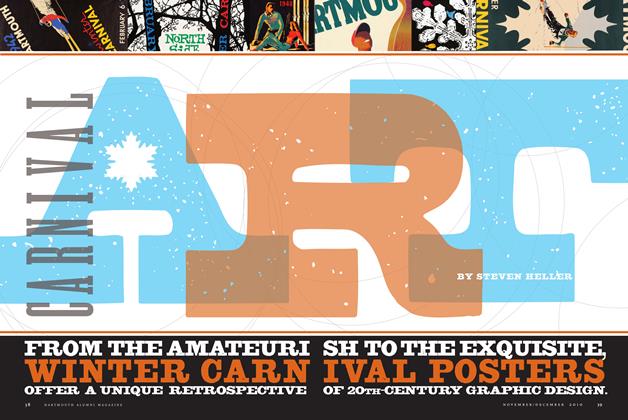

FeatureCarnival Art

Nov/Dec 2010 By STEVEN HELLER