A government professor looks at presidential elections

Last fall, George Bush won the presidency by successfully defining the terms of debate and exploiting the weaknesses of his relatively unknown Democratic opponent. Against a background of American flags and other patriotic symbols, the vice president skillfully used the issues of the American Civil Liberties Union, gun control, escaped furlough prisoner Willie Horton and the pledge of allegiance to portray Governor Michael Dukakis as an ultra-liberal too far to the left for a majority of voters.

Even though Bush trailed by as much as 17 points in the polls early in the campaign, his victory was hardly unexpected. It is consistent with the trend toward Republican dominance at the presidential level that began in the turbulent late'60s. The Bush win, along with Republican victories in four of the five previous presidential contests, raises a central question in American politics: Why can't the Democrats—the majority party—capture the White House?

The main problem confronting the Democratic Party is that it has lost control of the political agenda. Between the '30s and the mid-'60s the Democrats dominated political debate at the national level by advocating an expansion of the federal government's role in regulating the economy and in providing social-welfare benefits. This helped to transform the image of both major parties and polarize electoral politics along class lines to a considerable extent. The politics of class were powerful enough to hold together the diverse elements of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal coalition and enable Democrats to be competitive in the race for the presidency until the mid-'60s.

The events and issues of the '60s and '70s transformed the American political agenda, shattered the Democratic coalition and undercut its ability to capture the White House. The long-simmering issues of race and civil rights and the emergence of a new set of social issues, including abortion, street crime, and permissive lifestyles, divided Democratic liberals and conservatives. Vietnam and the question of the relevance of the Third World to American national security divided Democratic hawks and doves. Finally, the perceived failure of Lyndon Johnson's Great Society programs and the weakness of the economy in the Carter years called into question the Democrats' competence in their traditional areas of strength—managing social welfare and regulating the economy.

Unfortunately for the Democrats, the post-1968 democratization of the presidential nomination system has compounded the problem posed by the issue conflicts dividing the party. The new rules shifted the power to make the nomination from traditional party elites to issue-activists and rank and file voters. This change has vastly increased the complexity of the nomination process and, as the selections of George McGovern, Walter Mondale, and Michael Dukakis demonstrate, has failed to produce on a consistent basis a centrist candidate capable of leading the party to victory.

Yet at the congressional level, Democratic Party prospects remain bright. Except for brief periods, the Democrats have exercised control of both houses of Congress since the '30s. The issues dividing the party in presidential politics are less damaging at the congressional level for two reasons. First, unlike their presidential running mate, Democratic congressional candidates do not typically have to appeal to all segments of the party in order to win. If they choose to run on issues, northern Democrats can win by taking moderate to liberal positions, while southern Democrats can win by assuming moderate to conservative stances. Second, congressional incumbents of both parties can muster finances and media resources to reinforce their images as trustworthy, capable individuals who look out for the interests of their state or district. By playing up constituent service, Democratic incumbents have been able to insulate themselves from the issues dividing the party nationally.

Will the emergent divisions within the Democratic party enable the Republicans to continue their presidential winning streak through 1992 and beyond? Not necessarily. The Democrats still maintain some of their traditional partisan advantages. They remain the majority party. In addition, the fiscal policies of the Reagan administration reinforced the image of the Republicans as the party of the economically privileged and the Democrats as the party of the average citizen. These longstanding images of the parties and the nomination of centrist candidates capable of promoting party unity hold the key to future Democratic presidential victories.

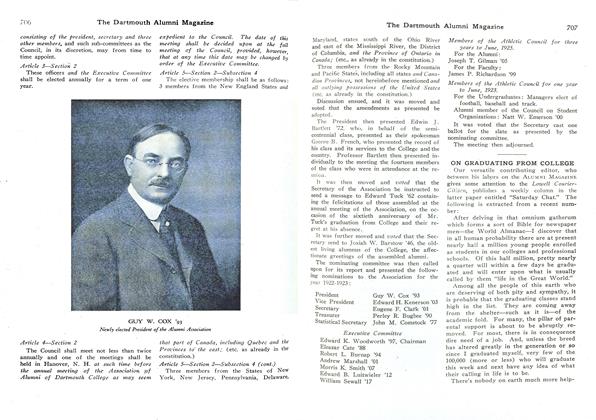

Although Hanover is far removed from the Washington power mill, Assistant Professor of Government Robert Arseneau finds Dartmouth an exciting place from which to observe the general election. "When candidates come north, they come here," he says, leaning back in his chair. "Sometimes they even come to my office."

Arseneau had more than just academic interest in studying the last election: he was also vice-chairman of the local Democratic Party. During the primaries he supported Bruce Babbitt. "I didn't think he could win," Arseneau explains, "but I was impressed by his candor and his willingness to address controversial issues like entitlements and taxes."

It wasn't political ambition of his own that drew Arseneau to study government, but rather his experience in the merchant marine during the Vietnam War. "I wandered around the major ports from Danang to Saigon for two months in 1967, interacting with soldiers and with Vietnamese out of curiosity and friendship," he recalls. "When I returned to school, I took courses in political science in an effort to understand American intervention in the Vietnam conflict." He says that after two more trips to Vietnam "the power of tradition there impressed me and made me wonder about our ability to change that country into what we wanted to create."

Arseneau's questions led him to graduate school at Berkeley, where he studied political behavior and American government. He worked under Raymond Wolfinger, one of the foremost authorities on voter turnout and congressional elections, as well as with the eminent political psychologist Herbert McClosky. Since coming to Dartmouth in 1983, Arseneau has tried to give his students "a sense of the importance of exercising power judiciously," as he puts it. For example, in his course on the presidency, he assigns David Halberstam'sThe Best and The Brightest, which documents the development and implementation of policy concerning Vietnam and Southeast Asia from Truman through Johnson. "Many students identify with the political elites discussed in this book," observes Arseneau. He then assigns Philip Caputo's A Rumor of War, a nightmarish account of combat life in Vietnam. "My purpose is not to make converts," the professor asserts. "At best you leave people with doubts."

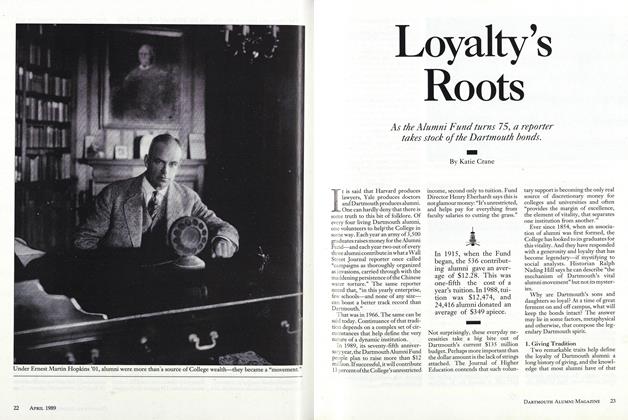

Professor Arseneau with a former Democrat.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLoyalty's Roots

April 1989 By Katie Crane -

Feature

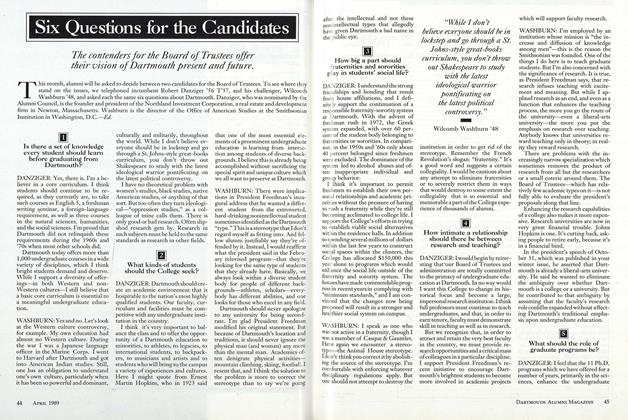

FeatureSix Questions for the Candidates

April 1989 -

Feature

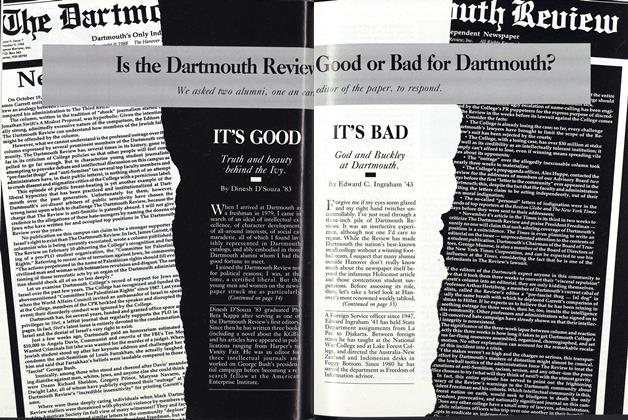

FeatureIT'S GOOD

April 1989 By Dinesh D'Souza '83 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S BAD

April 1989 By Edward C. Ingraham '43 -

Feature

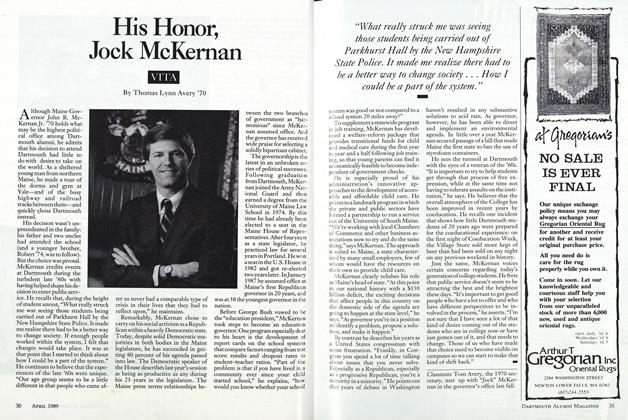

FeatureHis Honor, Jock McKernan

April 1989 By Thomas Lynn Avery '70 -

Feature

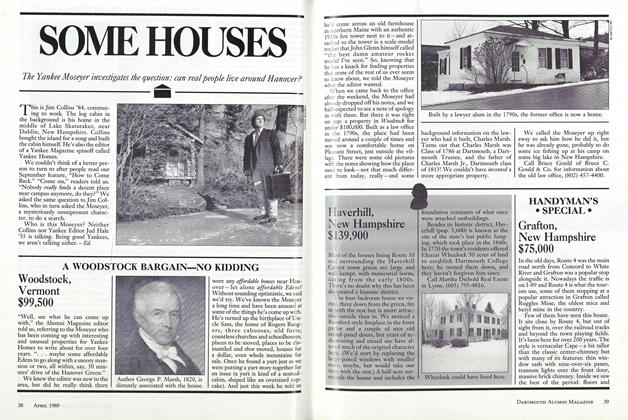

FeatureA WOODSTOCK BARGAIN—NO KIDDING

April 1989

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDaedalus with a Power Glove

OCTOBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCosmic Bubble Bath

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

APRIL 1998 By Karen Endicott -

HISTORY

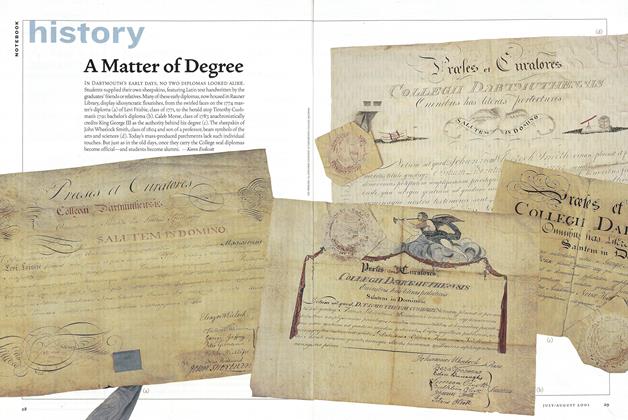

HISTORYA Matter of Degree

July/August 2001 By Karen Endicott