TAKING DISABILITIES SERIOUSLY MEANS REDEFINING HOW STUDENTS GET AN EDUCATION.

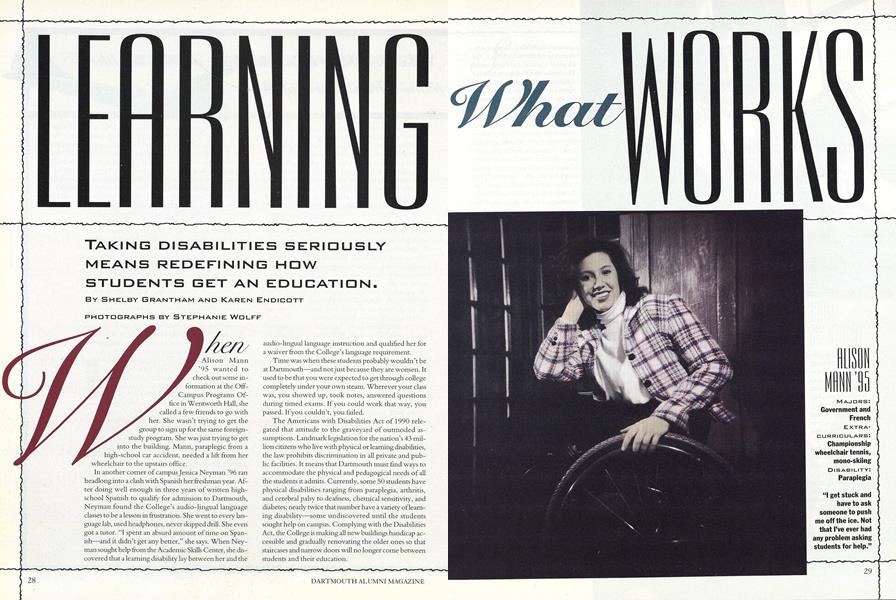

When Alison Mann '95 wanted to check out some information at the Off-Campus Programs Office in WentworthHall, she called a few friends to go with her. She wasn't trying to get the group to sign up for the same foreign-study program. She was just trying to get into the building. Mann, paraplegic from a high-school car accident, needed a lift from her wheelchair to the upstairs office.

In another corner of campus Jessica Neyman '96 ran headlong into a clash with Spanish her freshman year. After doing well enough in three years of written highschool Spanish to qualify for admission to Dartmouth, Neyman found the College's audio-lingual language classes to be a lesson in frustration. She went to every language lab, used headphones, never skipped drill. She even got a tutor. "I spent an absurd amount of time on Spanish and it didn't get any better," she says. When Neyman sought help from the Academic Skills Center, she discovered that a learning disability lay between her and the audio-lingual language instruction and qualified her for a waiver from the College's language requirement.

Time was when these students probably wouldn't be at Dartmouth and not just because they are women. It used to be that you were expected to get through college completely under your own steam. Wherever your class was, you showed up, took notes, answered questions during timed exams. If you could work that way, you passed. If you couldn't, you failed.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 relegated that attitude to the graveyard of outmoded assumptions. Landmark legislation for the nation's 43 million citizens who live with physical or learning disabilities, the law prohibits discrimination in all private and public facilities. It means that Dartmouth must find ways to accommodate the physical and pedagogical needs of all the students it admits. Currently, some 50 students have physical disabilities ranging from paraplegia, arthritis, and cerebral palsy to deafness, chemical sensitivity, and diabetes; nearly twice that number have a variety of learning disability some undiscovered until the students sought help on campus. Complying with the Disabilities Act, the College is making all new buildings handicap accessible and gradually renovating the older ones so that staircases and narrow doors will no longer come between students and their education.

The College is also undertaking another kind of renewal one that is taking the measure of what happens inside Dartmouth's hallowed halls. For in thinking about how to meet the challenges of students with physical or learning disabilities, educators are slowly beginning to think differently about education itself.

And that means re-examining the way classes are taught. One of the College's more progressive classroom rethinkers, physics professor Delo Mook, is actually rewriting his introductory physics course with the help of students who have the most trouble with it. Working individually with students until they find some way of explaining physics that makes sense to them whether by means of color-coded diagrams, animated drawings, comparisons to musical notation, or even poetry about gravitational fields Mook encourages them to write up their explanations and file them on a computer disk for other students to consult. Mook's bottom line in teaching as well as in learning: "Whateverworks."

For some students, though, just getting to class is the first hurdle. After a slow start the College has made progress toward making it easier for physically disabled students to get around. It gives wheelchair users like Mann first priority in dorm rooms and arranges for their classes to be held in accessible rooms. The College built a ramp at Mann's sorority, one of the case-by-case renovations Dartmouth has been undertaking as specific needs arise. Taking a more proactive approach, the College has renovated the Admissions Office, the Hopkins Center, and Dartmouth, Thornton, and Parkhurst halls for wheelchair accessibility, and has bought an accessible van. Priorities for the future include renovating Robinson Hall, home of the Outing Club, The Dartmouth, and the College radio station; renovating more dorm rooms for accessibility; building ramps for Rollins Chapel and Brace Commons in the Zimmerman, Andres, and Morton dorm complex; installing power doors and lever doorknobs; and equipping College cars with hand controls. For the blind, there will be more Braille markings. For the deaf, more listening devices and conference microphones. And the Ravine Lodge, gateway to the Dartmouth experience, will get a wheelchair lift.

But the campus is a big place, and there is still a long way to go. Recognizing the financial and logistical difficulties of rapid and full compliance, the Disabilities Act provided some leeway for older institutions like Dartmouth. Facilities built before 1977 can be "viewed in their entirety" when accessibility is assessed. Merely providing a ground-floor room for classes can be construed as compliance in such buildings, though the limitations are obvious, Even renovated buildings have their shortcomings. Despite the work that was done on Parkhurst for example, wheelchairs still cannot roll into the president's office. Peter Gamble '98, a 29-year-old navy veteran who became paraplegic in the line of duty, literally bumps up against such obstacles all over campus. Kiewit's "accessible" bathroom door turned out to be too narrow for his wheelchair, as was Baker Library's "accessible" elevator. Here's what happened when he tried to use the Composition Center, located up three flights of stairs in Sanborn. "I called and explained the situation," Gamble says. "Someone agreed to meet me downstairs but never got there. I found a phone and tried to call up, got the wrong person, had to explain all over. When I phoned about retrieving my paper, I was told to pick it up upstairs. I explained again. Finally the janitor brought the paper down. Everyone was pleasant and well-intentioned, but I ought not to have to explain over and over." Urging the College to comply quickly and fully with all Disabilities Act guidelines, Gamble says, "ADA is a good law. They thought about it a lot and got input from the blind, the deaf, wheelchair users, all sorts of disabled people. And I like to think I'm looking out for the guys who will be here down the line."

Students ARE FINDING QUICKER fixes for certain aspects of classroom participation. Diabetic Mace Turner '95, explains to his professors that his blood sugar fluctuations mean that he can't manage back-to-back exams and that sometimes he may even have to postpone taking an exam. "People are generally receptive," he reports. Fellow '95 Wendy osterling, who is profoundly deaf, uses a variety of strategies to get the most out of classes. She lipreads She asks her professors to use a special FM system the College bought for her. The receiver she wears cuts background noise and strengthens voices: all the prof has to do is slip a special microphone into a pocket. She asks professors for copies of their lectures and depends on fellow students to be her ears, helping her with notetaking, most recently right onto a laptop computer. And she relies on the silent efficiency of Blitz Mail, the College's e-mail system, for instant access to professors, students, the library, the Internet, the world.

Similar measures, so sensible and unobtrusive that they barely seem like accommodations, work in Dartmouth's extracurricular world as well. Alison Mann plays championship tennis from a wheelchair. Osterling is a championship cross-country skier. Rob Nutt '98, who has been progressively losing his hearing since age four, is a rower. "My teammates seem to understand that I just won't get a change in stroke sometimes. The coxswain gives a command, which I don't hear. Since I don't change the stroke with the rest of the boat, the rhythm is interrupted, but then I correct myself and we continue on. No intolerance, no impatience. It works out," he says. As John Stanton '93, profoundly deaf since age four, explained during his Dartmouth football days. "In most sports you don't need to hear. The football huddle was invented by a deaf team so were baseball's umpire signals. Lipreading through Facemasks is difficult, so I couldn't play offense." The solution: he became a linebacker. "It took the coach a while to remember to face me. He couldn't yell at me from the sidelines," says Stanton. Clearly deafness hasn't blocked him from his goals on or off the football field. Stanton won the Class of 1866 Oratory Championship and is now a law student at Georgetown.

Just as these physically disabled students have found ways to make their studies and extracurriculars work, students with learning disabilities also have to find educational methods and strategies that work for them. But first they have to find out what the problem is, and that is no easy task.

Asked to define a learning disability, College psychologist Bruce Baker takes a deep breath. '"Learning disability' is not a clear diagnostic category." He pauses. "No one thing makes it they have brought together behaviors and observations and said, ex post facto, that a student having them is learning-disabled."

Scientific American calls a learning disability "a subtle language deficiency." The New York Times describes it as "difficulty learning to read despite adequate intelligence and conventional instruction." Dartmouth's disabilities coordinator. Nancy Pompian explains it as "a neurological miswiring in the brain that complicates information-processing tor specific tasks in people of average or above-average intelligence. It affects learning, storage, and retrieval of certain kinds of information linguistic, mathematical, and visual and spatial reasoning."

Indeed, learning disabilities include a dizzying array of educational challenges: dyslexia (difficulty reading), dysnomia (difficulty speaking), dysgraphia (difficulty writing), dyscalculia (difficulty calculating), and difficulty with auditory processing trouble making sense of what is heard). Researchers from educators to neuropsychologists to language pathologists are still struggling to define and diagnose learning disabilities and figure out what to do about them. Meanwhile, it's clear that a person can have a learning disability diagnosed or not and still be a rocket scientist. Among the more famous dyslexics, for example: Leonardo da Vinci, William Butler Yeats, Thomas Edison, Woodrow Wilson, Nelson Rockefeller '29, and Albert Einstein. (Einstein wasn't even much of an arithmetician, according to the late mathematician John Kemeny, who helped the twentieth-century's greatest genius with calculations.)

Yet THE VERY IDEA THAT Intelligent, creative, successful Achievers can have learning disabilities still surprises people at Dartmouth and other highly selective colleges. If students are smart enough to get into Dartmouth, the reasoning goes, how could they have a learning disability? What's more, if they have a learning disability how could they do well enough to get into Dartmouth?

A 1988 study by Pompian and Carl Thum, director of the College's Academic Skills Center, revealed that two-thirds of such students didn't even know they had learning disabilities until they came to Dartmouth. Averaging an IQ of 122, holding timed SAT scores of 630 verbal and 580 math, and sharing a history of excellent high school achievement, good study skills, and well-developed social and communication skills, the learning-disabled students in the study looked much like everyone else at Dartmouth.

But something strange was happening in class.

Drill in Dartmouth's audio-lingual French course was a nightmare for one '94 who prefers to remain unnamed. "I would sit there going 'Ahhhh—' while everyone waited, annoyed, antsy, huffing and puffing, looking at their watches. I felt stupid," she says.

Jessica Neyman the '96 who worked incessantly on Spanish, could almost feel her mind's struggles. "You have to take in a sentence, keep it in your brain somewhere while you go to some other part of your brain to get the words for translating it. I always lost the sentence," she says.

Taking exams in a crowded room undid a '93 who requests anonymity. "People chewing gum or gnawing pencils drive me crazy. I read a word problem. I read it three more times. I draw diagrams, write the question over, circle words, underline words. And the person next to me is writing furiously, flipping pages like mad, already done. I feel so stupid," she said at the time.

With a verbal-scale IQ of 144 and a magna cum laude degree from Harvard, Bostonian Saul Weiner DMS '94 knows he's not stupid. He also knows he has a learning disability. "French was my first language but I failed it at the Park School even though I could speak it well. I was almost asked to leave Roxbury Latin," he says. "In seventh grade I cried many nights. I reversed letters, mirror-wrote, misspelled easy words, forgot number order. The teacher would call on me and I would panic, thinking, 'Does 70 or 80 come first? How do people remember? There are so many numbers!'"

First years at medical school are notoriously difficult, and the beginning of Weiner's was "a horror." When his fellow medical students with learning disabilities requested help, they were told to see a movie with their spouses or were referred to psychiatrists who advised taking more notes. "All wrong," says Weiner. "The best advice for anyone with learning disabilities is: 'Trust yourself and what works for you.'" He decided that lectures didn't work for him. "I took a deep breath and phased out of classes during Christmas of my first year. I didn't attend a single class after that. I got syllabi and spent all day at home studying, showed up for tests, and passed everything."

Sometimes doing what works cuts right against the grain of what people expect education to look like. "I've never read a book," dyslexic Joan Corstgha Breen DMS '88 once told a Dartmouth faculty committee on disabilities. "She knew how to read," disabilities specialist Pompian explains, "but it took so much time and pain, she preferred other ways of learning. A good note-taker, she never missed class, asked questions, talked to professors and friends, and 'thought a lot.'"

With each tale of frustration, each hard-won success, Dartmouth has learned a little more about how to help students who may not yet know their best learning strategies. According to Pompian and Thum, deans, professors, and students increasingly recognize that if a student is working hard but getting nowhere it's time to look into the possibility that the student has a learning disability. If diagnostic tests reveal a disability, the student can get help with learning how to learn best.

Often that means letting common sense break through educational habits of the individual and the institution. "Accommodation is the answer," says learning specialist Ann Silbergarb, who evaluates learning disabilities for the College. A case in point: when the Tuck School sought her advice on how to help a brilliant student who kept flunking tests, Silberfarb asked the deans, "How would he cope in business?" "Oh, he would dictate everything to a secretary," they replied. "Well, let him do that on his tests," suggested Silberfarb. The student was soon making A's.

Sometimes learning disabilities require students to work longer than others. Dyslexics do not read in phrases or sentences or paragraphs but word by word, and because they misread words regularly, they must re-read sentences several times to get them right," explains Silbergfarb "They are reduced to writing letter by letter rather than in phrases, sentences or paragraphs, which causes them to lose the flow of ideas and thwarts their productivity as well as the quality of their writing. The slowness of their processing causes anxiety and stress that further inhibits their productivity as well as their confidence as a learner....Time is the critical issue in survival for a college-level dyslexic."

Technology may increasingly bend time for learning-disabled students. Silberfarb pictures the day when students will take all their tests in their own rooms via computer or dictaphone. "So what if it takes 15 minutes or two hours?" she remarks. Another time-saver for learning-disabled students: voice-activated computers that handle the typing, spelling, and punctuation hurdles that often get in the way of their educations.

Obviously, faculty must be part of these solutions. According to Silberfarb, most professors make the effort to accommodate learning-disabled students when they realize that they are not being asked to lower standards, but to extend their lessons to everyone. For just as there is no one way to learn, there is no one way to reach all students disabled or not.

"Learning disabled' is a misnomer," insists Delo Mook, who last year received the College's Distinguished Teaching Award from the senior class. "We are all learning disabled thank God. A better phrase would be 'learning anomalous.' Your way is not the way you are being taught.

"I am trying to address anomalous learners. I don't time exams, for instance. Yes, there is a correlation between speed and knowledge, but not when you are first learning a subject. Timed exams in an introductory course are ridiculous. I also let students retest later, if they want, for a higher grade. The students are paying me to teach physics, and that's what I'm going to do."

Not many professors have rethought education as fully as Mook. But slowly that may come. For student by student, professor by professor, the reward shines clearer: Learning what works is an education for life.

ALISON MANN '95 MAJORS: Government and French EXTRA CURRIGULARS: Championship wheelchair tennis, mono-skiing DISABILITY: Paraplegia "I get stuck and have to ask someone to push me off the ice. Not that I've ever had any problem asking students for help."

MACETURNER '95 MAJOR: Psychology EXTRA CURRICULARS: Baptist StudentFellowship,horseback riding,piano DISABILITY: Diabetes"I can miss onemeal, but not tworunning. I loseconcentration,can't focus, haverandom thoughts,get irrationallyirritable."

LORRIANE BAUTISTA DMS '95 EXTRA CuRRICULARS: Soccer, school volunteering HOME LIFE: Raising two children DISABILITY: Auditory processing "Sometimes I need to be really attentive to make sure I catch what people are saying or to make sure I understand it during a lecture."

ROB NUTT '98 MAJOR: Undecided EXTRACURRICULARS! Crew DISABILITY: Progressivehearing loss"Since I don'tchange thestroke with therest of the boat,the rhythm isinterrupted, butthen I correctmyself and wecontinue on."

SHELBY GRANTHAM teaches English at Dartmouth andis a former senior editor of this magazine. KAREN ENDICOTT is faculty editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSlicing in the Wilderness

May 1995 By Glen Waggoner -

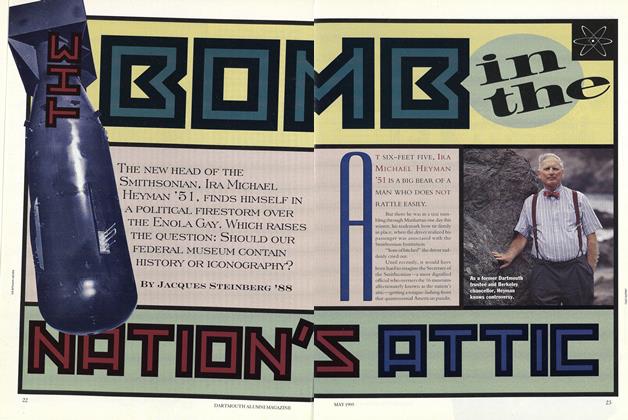

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Bomb in the Nation's Attic

May 1995 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Article

ArticleCosmic Bubble Bath

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

May 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleHISTORY THAT WON'T FLY

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1995 By Daniel Zenkel

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCongress Authorizes National Medal

APRIL 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryKenneth '25 and Harle Montgomery

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

FEBRUARY • 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1967

JULY 1967 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY