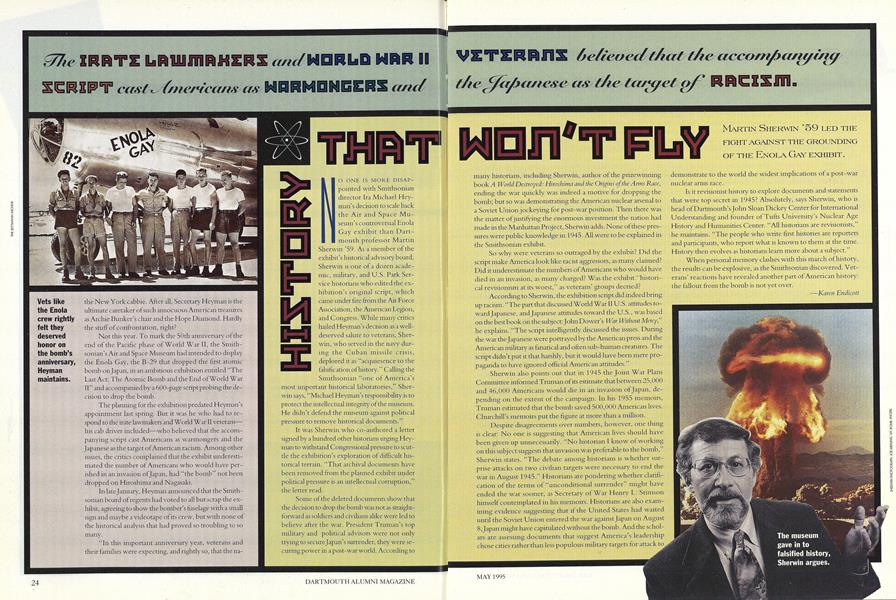

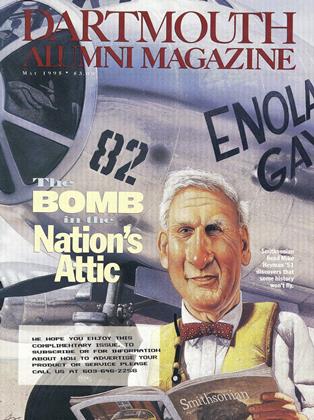

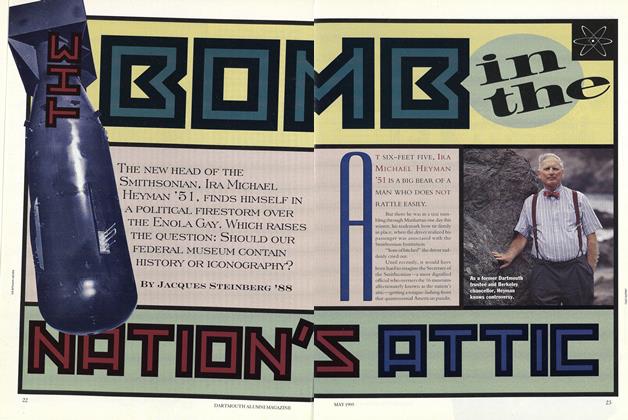

MARTIN SHERWIN '59 LED THE FIGHT AGAINST THE GROUNDING OF THE ENOLA GAY EXHIBIT.

NO ONE IS MORE DISAPpointed with Smithsonian director Ira Michael Heyman's decision to scale back the Air and Space Museum's controversial Enola Gay exhibit than Dartmouth professor Martin Sherwin '59. As a member of the exhibit's historical advisory board, Sherwin is one of a dozen academic, military, and U.S. Park Service historians who edited the exhibition's original script, which came under fire from the Air Force Association, the American Legion, and Congress. While many critics hailed Heyman's decision as a welldeserved salute to veterans, Sherwin, who served in the navy during the Cuban missile crisis deplored it as "acquiesence to the falsification of history." Calling the Smithsonian "one of America's most important historical laboratories," Sherwin says, "Michael Heyman's responsibility is to protect the intellectual integrity of the museum. He didn't defend the museum against political pressure to remove historical documents."

It was Sherwin who co-authored a letter signed by a hundred other historians urging Heyman to withstand Congressional pressure to scuttle the exhibition's exploration of difficult historical terrain. "That archival documents have been removed from the planned exhibit under political pressure is an intellectual corruption," the letter read.

Some of the deleted documents show that the decision to drop the bomb was not as straight-forward as soldiers and civilians alike were led to believe after the war. President Truman's top military and political advisors were not only trying to secure Japan's surrender, they were securing power in a post-war world. According to many historians, including Sherwin, author of the prizewinning book A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and the Origins of the Arms Race, ending the war quickly was indeed a motive for dropping the bomb; but so was demonstrating the American nuclear arsenal to a Soviet Union jockeying for post-war position. Then there was the matter of justifying the enormous investment the nation had made in the Manhattan Project, Sherwin adds. None of these pressures were public knowledge in 1945. All were to be explained in the Smithsonian exhibit.

So why were veterans so outraged by the exhibit? Did the script make America look like racist aggressors, as many claimed? Did it underestimate the numbers of Americans who would have died in an invasion, as many charged? Was the exhibit "historical revisionism at its worst," as veterans' groups decried?

According to Sherwin, the exhibition script did indeed bring up racism. "The part that discussed World War II U.S. attitudes toward Japanese, and Japanese attitudes toward the U.S., was based on the best book on the subject: John Dower's War Without Mercy", he explains. "The script intelligently discussed the issues. During the war the Japanese were portrayed by the American press and the American military as fanatical and often sub-human creatures. The script didn't put it that harshly, but it would have been mere propaganda to have ignored official American attitudes."

Sherwin also points out that in 1945 the Joint War Plans Committee informed Truman of it's estimate that between 25,000 and 46,000 Americans would die in an invasion of Japan, depending on the extent of the campaign. In his 1955 memoirs, Truman estimated that the bomb saved 500,000 American lives, Churchill's memoirs put the figure at more than a million.

Despite disagreements over numbers, however, one thing is clear: No one is suggesting that American lives should have been given up unnecessarily. "No historian I know of working on this subject suggests that invasion was preferable to the bomb," Sherwin states. "The debate among historians is whether surprise attacks on two civilian targets were necessary to end the war in August 1945." Historians are pondering whether clarification of the terms of "unconditional surrender" might have ended the war sooner, as Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson himself contemplated in his memoirs. Historians are also examining evidence suggesting that if the United States had waited until the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan on August 8, Japan might have capitulated without the bomb. And the scholars are assessing documents that suggest America's leadership chose cities rather than less populous military targets for attack to demonstrate to the world the widest implications of a post-war nuclear arms race.

Is it revisionist history to explore documents and statements that were top secret in 1945? Absolutely, says Sherwin, who is head of Dartmouth's John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding and founder of Tufts University's Nuclear Age History and Humanities Center. "All historians are revisionists," he maintains. "The people who write first histories are reporters and participants, who report what is known to them at the time. History then evolves as historians learn more about a subject."

When personal memory clashes with this march of history, the results can be explosives, as the Smithsonian discovered. Veterans' reactions have revealed another part of American history: the fallout from the bomb is not yet over.

The museum gave in to falsified history, Sherwin argues.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSlicing in the Wilderness

May 1995 By Glen Waggoner -

Feature

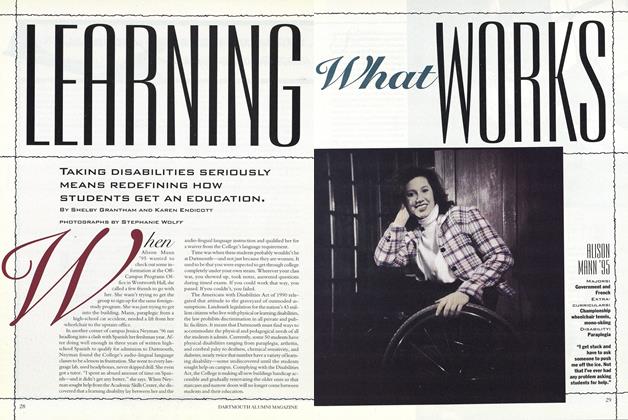

FeatureLEARNING WHAT WORKS

May 1995 By Shelby Grantham and Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Bomb in the Nation's Attic

May 1995 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Article

ArticleCosmic Bubble Bath

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

May 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1995 By Daniel Zenkel

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJorge Hernandez Martin "...he makes the faraway immediate."

June 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleGaudeamus Igitur!

September 1993 By karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOut of the Literary Closet

NOVEMBER 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHEN POETRY SPEAKS

FEBRUARY 1991 By Professor Cleopatra Mathis, Karen Endicott